50 years on: How Leeds and Reading Festivals began in church

It is a hedonistic summer ritual that began, of all places, in church.

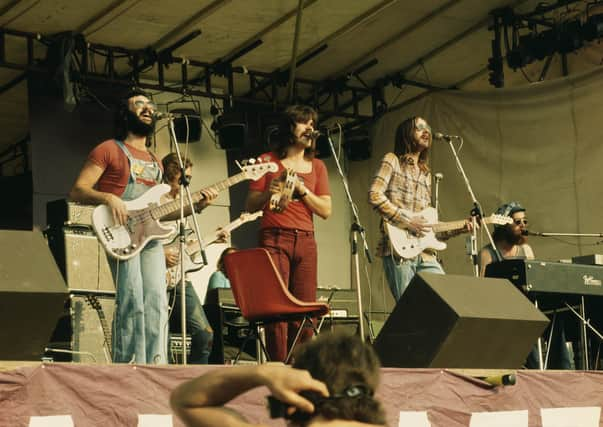

Half a century ago this coming summer, the crowds began turning up on the banks of the Thames to worship at the altar of the high priests of rock and roll. The first Reading Festival was a watershed in British music history, the moment at which vast outdoor gatherings became part of the commercial mainstream. And although it would be another 28 years before the party moved north to Leeds, the rite of passage had been established for a generation.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIt cost just £2 to see Lindisfarne, Rory Gallagher and Ralph McTell headline three days of performances at what the poster called a “beautiful Thames-side camp site and arena” half a mile from the town centre. Reading Council had allowed it to go ahead as an experimental addition to its decade-old jazz and blues festival. They could not have known what they were unleashing.

There had been outdoor music gatherings in Britain before – on the Isle of Wight from 1968 and at Glastonbury from 1970. But they had grown out of the “free festival” movement spawned by the hippie counterculture of the late 1960s. Reading was never anything other than materialistic.

Yet, as one Yorkshire academic pointed out, it had its roots in a much earlier form of musical celebration.

“Actually, it can be traced back to the Christian church hundreds of years ago,” said Rupert Till, a professor of music at Huddersfield University.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“They didn’t originally have pews, and that meant people were able to start dancing in church, which was considered unseemly. So they created festive days, including the Christian festivals we have now, which people could enjoy outside in the churchyard.

“They would celebrate the good weather or some other joyous occasion with some kind of feasting which always included music and dance.

“It still happens in some countries. If you go to a village in Italy or in Spain on one of these days, everything will come to a standstill and the whole village will be out, celebrating the festival.”

In Britain, the tradition developed in a more idiosyncratic way, Professor Till said, with gumboots and sun cream in equal measure in deference to the changeable climate.