A history entwined: Leeds United and city’s Jewish community

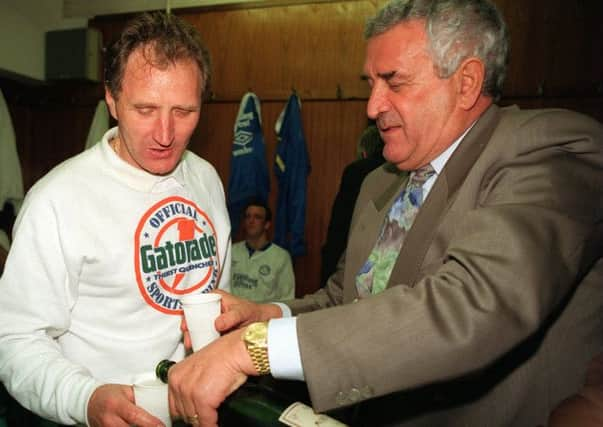

THE sad passing of former Leeds United chairman Leslie Silver provided an opportunity for reflection for the Jewish community in Leeds.

In fact, many members of it have spoken about the huge influence the football club provided when it came to them becoming more integrated with the city as a whole.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIn the 1930s, Leslie Goldberg appeared regularly for Leeds United at right-back, the first sign of the Jewish community embracing its local football team.

Goldberg was born in Leeds in 1918, and, as a result, qualified to play for the English national side. However, he only received a call-up to the team when he Anglicised his name after moving to Reading, changing it to Les Gaunt.

As Mavis Solk, from near Roundhay, said: “You felt a little bit ashamed if you had a Jewish name.”

By the time Leslie Silver joined the board of the Elland Road club at the end of the 1983 season, the Whites had had a Jewish chairman in Manny Cussins, and the community had spread across the city.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIt moved north, towards Moortown and Alwoodley, forming the infrastructure of the Jewish population of Leeds that can still be seen today. Silver was the second Jewish chairman to lead the club to the league championship in 1992, the club’s last trophy. The community had embraced the city and the club.

At the time of Leslie Goldberg’s appearances for Leeds, the situation was vastly different.

Waves of immigration had brought Jewish people, often impoverished, to the city. Much like the rest of their history, the city’s Jews established a community centred around Chapeltown reflecting the same living arrangements as those found in Europe.

While not everyone in Chapeltown was Jewish, David Bickler, of Alwoodley, suggested that a “pretty high proportion” of his neighbours were.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdLocation aside, the nature of Jewish existence at the time meant that there were few opportunities to branch out and meet people from other backgrounds. The community was more religiously inclined at the time, and kept kosher in the main.

There was very little impetus to mix, and, in fact, the community discouraged it. Children were mainly introduced to the children of their parents’ friends, who would invariably turn out to be Jewish.

David Bickler recalls that “there were things Jewish people were expected not to do”, with places to socialise during childhood and young adulthood provided by the community itself.

It was not just that the community chose to close itself off to the wider city for no reason, said Mike Elbogan. He said it was “defensive mechanism in a way, as that way you didn’t meet any anti-Semitism”.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdInstitutional anti-Semitism still existed, with the Jewish Chronicle publishing an exposé in 1960 on the fact that Jews were discriminated against at local golf clubs.

Moor Allerton golf club was established in 1923, in part to provide a solution to the community’s desire to play the sport but finding no place that they were allowed to.

At the start of the 1960s, there was very little opportunity for the community to mix.What shattered that was the fact that the community, like the city itself, fell in love with Leeds United.

Legislation in the form of the Race Relations Acts of 1965 and 1968 can be partly credited with the change in outlook.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAt first, the common ground was Leeds rugby league club. Headingley was closer to the Jewish community.

In 1961, two important events occurred at Elland Road – Don Revie was appointed as manager and Manny Cussins joined the board.

Interest among Jews in the club was increased by the presence of a member of the community in a position of power, and like the rest of the city, as Revie brought success to the club, interest rose.

While attendances in the mid-1950s averaged around 20,000, a decade later over 46,000 watched Revie’s team crowned champions against Nottingham Forest.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAnthony Clavane wrote in Promised Land that “the community attached itself to Elland Road with a fervour unknown in more established football cities”.

It wasn’t the case that Jewish people were appearing among an already established fan base. They were equals on the terraces, not only in terms of their passion for Leeds United, but also the length of time they had followed the club.

The city’s population, both Jewish and non-Jewish, revolutionised their sporting habits as Revie revolutionised his team. This ended up having a huge effect on who people from the Jewish community would actually meet.

Going to watch Leeds became part of life for the Jewish population. Anthony Gilbert, a Rabbi at Etz Chaim Synagogue in Alwoodley, recalled that when growing up: “Shabbas (the Jewish holy day, Saturday) stopped at three o’clock because (people) went to the match at Elland Road. Maybe the fact they went to Elland Road was part of the shabbas as well, as far as they were concerned.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe club also embraced the Jewish community. Revie bought a house in Alwoodley, in the heart of the city’s Jewish population.

He joined Moor Allerton golf club, and holidayed with Jewish businessmen Gabby Harris and Leslie Silver.

Revie famously gave a sermon at a local synagogue, telling the Rabbi that while he had the congregation on a Saturday morning, they were his on an afternoon.

Jewish influence on the terraces can be seen by the fact that over the last 30 years, two players, Imre Varadi and Tony Yeboah, have had their names sung to the tune of Jewish folk song Hava Nagila.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdStephen Winehouse, who was born in 1961 at the start of Revie’s time in charge, believes that Leeds United, one of the greatest teams in Europe during his childhood.

He said: “The thing I had in common with kids my age that I had nothing in common with, with my different Jewish background, was Leeds United.

“I could approach people at school because everyone was barmy about Leeds United, it was all we thought about.”

It was that desire to see Leeds play that brought the community out of hiding and made it a part of the city itself. Revie’s side provided something that the community itself could not.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdLeslie Silver may have only become involved in 1983, but 20 years prior a revolution at Elland Road led to a revolution in the community itself.

In the last century, the city’s Jewish population have gone from an unknown entity established in a certain area to part of Leeds at large. A hundred years ago, members of the community could never envisage the passing of one of their own being memorialised on the front page of the local newspaper and, in part, Leeds United is responsible for that change. The involvement of great men like Silver has changed the circumstances for the city’s Jewish population immeasurably.