England's worst pit disaster - The day tragedy came to South Yorkshire pit community

On the morning of December 12, 1866, nearly 400 miners trudged to work as usual to the Oaks Colliery at Hoyle Mill just outside Barnsley.

It was just another ordinary day of hard graft but by the end of it most of them would be dead.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe colliery was not only one of the biggest pits in South Yorkshire, it was among the biggest in the country with miners coming from as far afield as Ireland, Wales and London’s east end to come and work there.

In Victorian Britain coal was the main source of power, helping drive the Industrial Revolution and fuel our ever-expanding global empire.

But it was dark, dirty work. The coal was dug out from deep mines underground and in dimly-lit tunnels scores of miners hacked at the coal with picks and shovels.

It could also be a deadly line of work and, in some cases, the men were effectively digging their own graves.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAt the Oaks Colliery they had known tragedy before. In March 1847, there was a firedamp explosion at the pit, killing 73 men and boys. But less than 20 years later an even bigger disaster was to befall its workforce.

The Oaks mined a seam that was notorious for firedamp, the name given to a number of flammable gasses, and on this fateful December day tragedy struck when methane gas was ignited and caused a huge underground explosion that ripped through the workings, less than an hour before the shift was due to end.

A party of pitmen managed to descend to the bottom of the shaft where they found a number of badly burned men who were sent up to the surface. The dead were taken to their homes and the survivors were given medical attention.

Of the 362 who were still working at the time of the explosion, only six survived. But the carnage didn’t stop there. A second explosion the next day killed 27 volunteer rescuers who were frantically trying to reach any survivors.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAt the time, the death toll was reported as 361 but research recently carried out by the Dearne Valley Landscape Partnership (DVLP) has unearthed the names of 294 men and 89 boys who perished.

It is the individual stories that make this tragedy so harrowing. Stephen Miller, community officer at the DVLP, says some of the victims were as young as 11. “The one that always stands out for me is Ezra Illingworth. He came from Wakefield and worked as a ‘nipper’, which was a general job given to children.

“He was one of the first bodies retrieved after the disaster and is buried at Barnsley cemetery in a pauper’s grave, as presumably his family couldn’t afford to pay for a headstone.”

It is the small details that bring home the human scale of the disaster. “At Hoyle Mill cottages there was only one house that didn’t lose somebody,” says Miller.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdNot that locals were the only people plunged into mourning. “Oaks was one of the biggest pits in the country. It mined deeper than another colliery and employed more people, it was huge in every way.”

That’s why he believes this anniversary ought to be marked. “It’s important nationally because of the scale of what happened and all the different places where people came from. It’s the human stories behind the bigger tragedy.”

Miller says volunteers have spent years doing research to help shed light on the tragic events that unfolded 150 years ago. “For years the Oaks Disaster had not received the attention it deserved but many more people are now aware of its significance. There has been a huge effort to make sure this anniversary doesn’t go unnoticed.”

The research, funded by The Heritage Lottery Fund, has helped uncover tales of bravery, too. Seventeen-year-old John Riley was the youngest volunteer to help with the Oaks Disaster rescue effort. He was walking home from a shift at the nearby Mount Osbourne Colliery when the explosion happened.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdA newspaper clipping from 1930, passed down through the family, includes an interview with John, who by this time was an old man, recalling how he descended the pit to try and rescue any survivors and retrieve the bodies of those killed.

“When I arrived at the pit the second explosion occurred. This blew the cage into the headgear, bricks and other things flew in all directions, and with so many people about, it was a wonder many of us were not killed.

“Those pals of ours, who had left us to go to the pit, went down with the last draw, and all perished. We should have met the same fate had we been a minute or two sooner.”

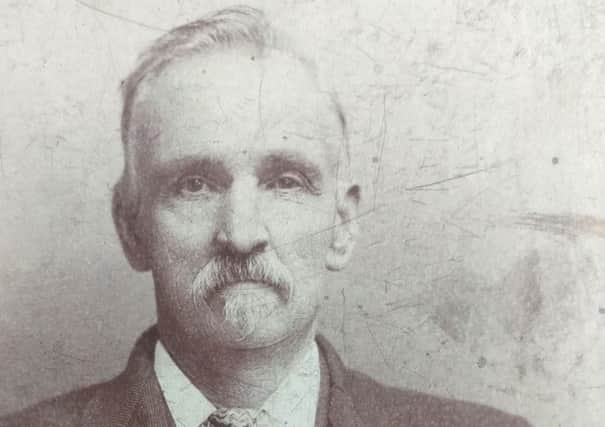

William Ward was another volunteer rescuer. He lost his father, John, in the first explosion and later played a key role in raising money for a memorial to the victims which was placed in the grounds at Christ Church, in Ardsley, in 1879.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdWilliam, who was himself a miner, was interviewed by the Sheffield Telegraph two days after the disaster. “I returned at five o’clock to learn the melancholy news. I dressed myself in pit clothes and went down to search for my father. I was in the mine eight hours and was to return at ten o’clock this morning. When I got to the bank the last explosion had taken place.”

It would be another two years before he and his brother finally discovered their father’s body.

There are now two memorials to the pit disaster – the second of which commemorates the bravery of the volunteer rescuers and was put up in 1913 – and soon there will be a third.

Local sculptor Graham Ibbeson has created a memorial which will take pride of place on Church Street in Barnsley town centre. The sculpture, commissioned to mark the anniversary, will be officially unveiled in May next year. It has cost £120,000 with most of the money raised by the local community.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdFor Ibbeson, whose family’s mining heritage stretches back 180 years and whose own father worked down the pits, the disaster has a personal resonance. “It’s just a few miles from where I was born and less than a mile from where I live now.”

He also lost a relative, his great uncle George Ibbeson, in the disaster. “It wasn’t until I started doing research into this that I found George was on the list of fatalities,” he says. “Like a lot of the miners he had a big family, I think he had six children. Can you imagine what it was like for them? There was no social security, no benefits, they were all living in squalor and it was just before Christmas...”

The town itself suffered, too. “There was the smell and the dirt and bits of debris that hung over Barnsley. It must have been like a war zone. But people picked themselves up and somehow managed to get on with their lives.”

It’s this resilience that he feels has helped mould Barnsley. “It’s not just about the miners it’s also about the community and how it coped and how it’s been able to recover because it devastated the whole town – nearly all the workforce was wiped out in one fell swoop,” he says.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe Oaks Colliery finally closed in the 1960s and for Ibbeson working on his sculpture and commemorating the anniversary is important for several reasons. “It’s about remembering all the miners who died all over the country while doing their job.”

And nowhere is that felt more keenly than in his home town. “It’s important to remember our heritage and here in Barnsley how the town came about. It really is important because this town was built on coal and this disaster ripples down through history.”

The Oaks Disaster remembered

There are a number of events planned this week.

Tonight there is a special event, open to the public, at the Town Hall featuring talks and readings. Among those attending will be relatives of those who died along with volunteers and groups involved in the anniversary. Ian McMillan has written a special poem to mark the occasion, which he will read at the event. There will be a special service at St Mary’s, Barnsley, at 7pm on Wednesday.

When the Oaks Fired, an exhibition that focuses on the human stories of the disaster, runs at Experience Barnsley until February 8.

For more details go to www.discoverdearne.co.uk and www.experience-barnsley.com