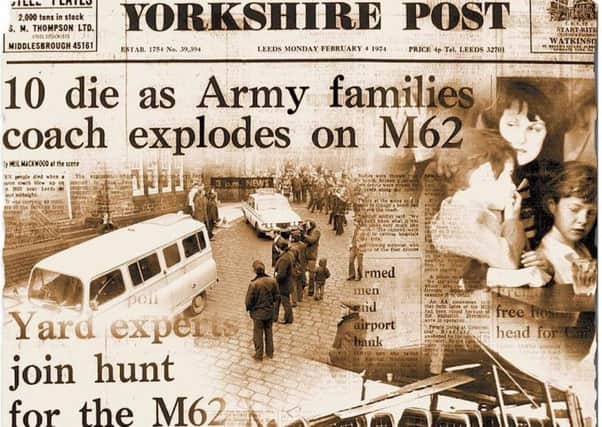

Motorway terror and a 40-year fight for justice

As the sun rose shortly before 8am on February 4, 1974, the extent of the devastation wreaked in a coach explosion just a few hours earlier became clear.

Amid the carpet of glass and twisted metal which covered part of the M62 carriageway lay broken gramophone records and a man’s shoe. A little further on was a Fusiliers cap and a child’s abandoned toy, all reminders of how the ordinary lives of a group of servicemen and their families had been shattered in an instant.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdA faint smell of burning hung in the air as firefighters continued a grim search of the area. One was asked what he was looking for. “Anything,” came the whispered reply. “Just anything.”

The coach had been one of five which had set off from Manchester to take the men, their wives and children back to army bases in North Yorkshire following weekend leave. Usually they would have caught the train, but ongoing industrial action on the railways had once again disrupted their plans and that Sunday night they had no choice but to go by road.

They’d set off sometime after 11pm and by the time they crossed the Pennines a few were enjoying a singalong. Others tried to grab some sleep and, this being the 1970s, the coach was filled with the fug of cigarette smoke.

At 12.20am what onboard chatter there had been was silenced. A 50lb bomb placed in the luggage boot was detonated and the explosion ripped through the coach. The driver, ignoring the blood streaming down his face, managed to steer onto the hard shoulder between Chain Bar and Gildersome. Opening his door, he stepped out into a bitter night, grabbing a torch to assess the damage. It wasn’t long before he found the first of the bodies. It was that of a child who he reckoned was no more than two.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdTwelve people – nine of them off-duty soldiers – died in the explosion. The eldest was just 28. The death toll also included a family of four. Corporal Houghton and his wife Linda had been sitting at the back of the bus, their two children, five-year-old Robert and Lee, on their knees. All were killed instantly.

One of the first reporters on the scene summed up the disbelief.

“The terrible truth that a terrorist bomb had exploded in Yorkshire had not occurred to me as I approached the flashing blue lights on the M62,” wrote Neil Mackwood in the following day’s Yorkshire Post. “The skeleton of the 49-seater coach, laid bare in the stark glare of arc lamps, was the grim reality. Behind it stretching for more than 200 yards was a trail of destruction. Wreckage littered the high embankment and more debris had been blasted across the motorway. All the evidence that the coach had been blown apart.

“I counted seven bodies, some covered with blankets hastily thrown over them before the ambulancemen carried them away. A policeman, filled with grief by what he saw, said: ‘You would never have thought it, something like this happening not 10 miles from Leeds’.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAs the emergency services struggled comprehend what had happened, behind the coach two young soldiers, their faces pale with shock, looked on. Both had escaped serious injury despite sitting together just three seats from the back of the bus. One wore a camouflage jacket. His nose was cut, his face black and his hair singed. Like most of the others on board, all he remembered of the explosion was “a bright flash followed by a loud bang”.

There were stories of other lucky survivors, like 18-year-old Signalman William Yeates. He’d spent the last few hours of his leave playing bingo with his family. The session had overrun and when he finally got to the coach his usual seat at the back was already taken forcing him to sit at the front away from the heart and heat of the explosion.

Hartshead Moor Services, which this weekend was once again the scene of a memorial service, was turned into an emergency shelter. There young soldiers sat in complete silence, gazing blankly into the distance, their hands clasped around coffee cups. As the rest of the country woke up and the realisation of what had happened began to sink in, that small stretch of motorway became the focus of a political storm.

“It’s senseless,” said one member of the Army bomb disposal team. “And it’s here in bloody Yorkshire.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdWhile the IRA had not claimed responsibility for the explosion, having previously boasted of plans to strike the British Army, attention turned across the Irish Channel.

Police were mobilised to explore every possible lead including cryptic personal column announcements which had been published in a Manchester newspaper.

“Precinct or meat s/market near 10 o’clock 23rd or 2 inc,” read one. A second said “Meat [sic] me at the market centre - Edwards.” The coach had been left in a car park near to the Edwards meat factor at 10pm on February 2 and detectives initially thought they may hold a clue to the identities of the bombers.

Pressure soon mounted on Scotland Yard and West Yorkshire Police’s head of CID, George Oldfield. The Government and the public wanted results and fast. They got them.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdJust 10 days after the explosion, the suspicions of a police dog handler from Liverpool were aroused when he saw a young woman peering at him from around a shop doorway. A brief conversation followed and on little more than a hunch he took her in for questioning.

By that November, 25-year-old Judith Ward was in the dock of Wakefield Crown Court facing 12 murder charges and accused of another two bombings. The trial was a media circus.

While the prosecution told the jury Ward was a gunrunner, bombmaker and vital cog in the IRA machinery, her testimony was often garbled and incoherent. Even her defence barrister admitted she may well have been “a Walter Mitty character desperate for a place in IRA folklore”, but the prosecution juggernaut kept rolling.

While significant doubt was cast on the forensic tests which one expert claimed proved the presence of nitroglycerine under her finger nails, the jury were swayed by the closing speech of prosecutor John Cobb QC.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdDescribing Ward as ruthless and lacking emotion, he said she had a passion only for her political aims which were to see the 32 counties combined into one Irish Republic. While acknowledging others should have been standing alongside, he concluded that “there are perhaps bigger fish in the sea, but she was no sprat”.

It took the jury five hours and 40 minutes to return a verdict. Ward was found guilty on all counts and sentenced to 30 years in prison with no recommended minimum term. It was not, however, the end of the story. For all those who had been touched by the M62 explosion there was more pain to come.