The diaries from hell: Yorkshire soldier's secret account of the Somme

At 7.30am on July 1, 1916 in trenches near the village of Serre in northern France, hundreds of men from Sheffield City Battalion 12th (Service) Battalion York and Lancaster Regiment stand and wait.

Watches are checked. Bayonets are fixed. Whistles are blown. Soldiers clamber out of their trenches and start the muddy trudge from John Copse into no man’s land. And thus begins the Battle of the Somme. No official war diarist is present to record what occurs during the long hours that follow. Instead Frank Meakin documents the events of the day.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

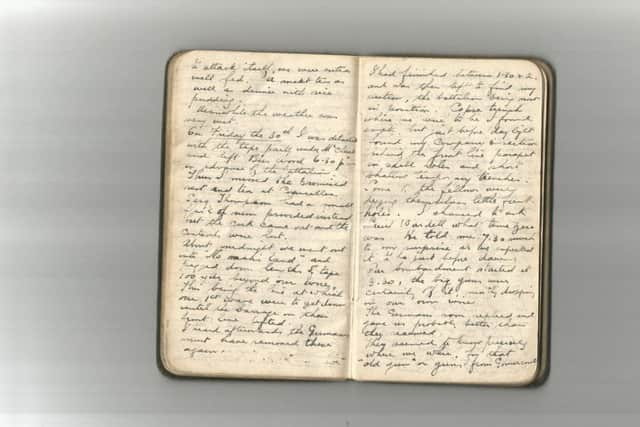

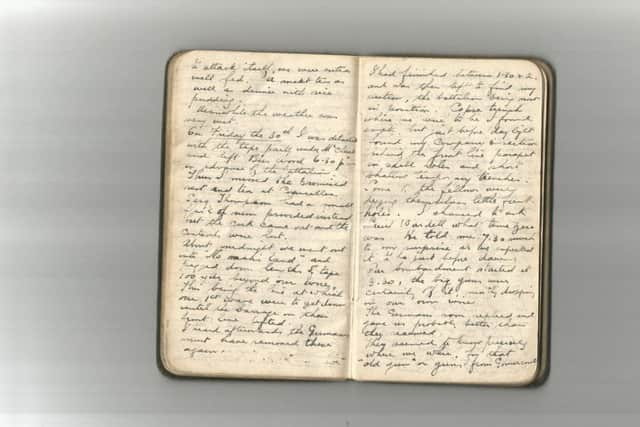

Hide AdFrank’s journey to the Somme can be traced via four diaries, an articulate and baldly matter-of-fact record of life before and during his time at the front. That they have survived is remarkable. That they existed at all is more remarkable still: soldiers were expressly prohibited from keeping diaries whilst on active service

Frank’s diaries have been dramatised in The Somme: The First 24 Hours, a new documentary by Sheffield-born writer/director Jeremy Freeston. Among those featured is Penny Meakin, the 61-year-old former teacher who painstakingly researched her husband’s grandfather’s diaries.

“It was absolutely forbidden to keep a diary, but a lot of them did,” says Penny. “The fact that he survived does make them, at least for this battalion, unique. And they’re tiny. The size of a tobacco tin.”

In 1914 Francis Meakin was a 34-year-old middle-class architect working for Sheffield City Council. When he decided to become one of the 2.5m men who enlisted in Kitchener’s unique volunteer army – known as ‘the Pals’ - he had only to go upstairs from his office in the town hall to sign the forms. Then came the eye-opening introduction to military life and several months in training at Redmires Camp on the outskirts of the city. Square-bashing complete, he and his comrades first went to Egypt before arriving in France in March 1916. Frank left behind Doll, his wife of six months.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“It goes from abject boredom to carnage,” says Penny. “That’s the telling thing about the diaries because that’s how their life was: ‘It rained today’ or ‘I had bacon for breakfast’. And then the next thing is they’re getting killed.”

We will remember them...

May 3 1916

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdBreakfast: very indifferent cold bacon. Dinner: bully beef. Tea: jam. We were allowed from 6-12 to sleep. I didn’t get much as the Germans shelled us. In the afternoon they fired shells and rifle grenades. The accuracy is steadily improving. One rifle grenade hit above me. Atkinson got shell shock. Todd gets a slight wound in his leg and expresses disappointment at it not being good enough for Blighty. While having it dressed a shell does the seven of them, poor fellows. They were all instantly killed apart from Todd, who lived nearly ‘til they got him to hospital.

Trench life is a long round of sharing personal space with lice and rats, patrols into no man’s land, one-to-one combat with the enemy, dodging barrages, rain and mud, consuming food and snatching sleep. On June 27 the men’s personal effects are collected.

“I am now putting this away with my private things. My last thought as I close this, Doll my darling, is how dearly I love you and my mother, too.”

Four days later the offensive begins. Frank would later claim that of the 650 men in his battalion, only 47 survived unwounded. On July 18 he recovers his diary and fills in the blanks.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAt about 7.15am [on July 1] I looked over to see what the section on the right had done and saw the small trench filled up. Then I saw the first wave going over. We got into the front line and followed at 7.25am. I found Captain Colley in the front bay and asked him the correct time. He pulled out his watch but could scarcely hold it, so shattered were his nerves. The poor fellow followed us all the same and was killed before he got very far.

On going over the top one of the first things he witnesses is a comrade with his rifle slung and “apparently off his head”, shouting and swearing at the enemy. Frank takes cover in a shell hole and waits for the British bombardment to stop. Arriving at the German wire he finds it “quite untouched in front of me”. But on the right is an opening. With seven other men he engages the enemy.

A British shell eventually knocks out the machine gun but Frank and his group are subjected to “showers of stick grenades”. The first and second lines of British soldiers are pinned down by aggressive fire from the German positions, preventing reinforcements from reaching them. Frank digs a short trench into the crater he’s in, giving him shelter and, amazingly, allowing him to doze.

“What I find mind-blowing is that Frank was an architect working in the town hall,” says Penny. “He signs up with his mates, most of them get killed but he survives. He comes home and goes back to his job. Post-traumatic stress disorder hasn’t been invented and you wonder why these men were so mentally damaged.”

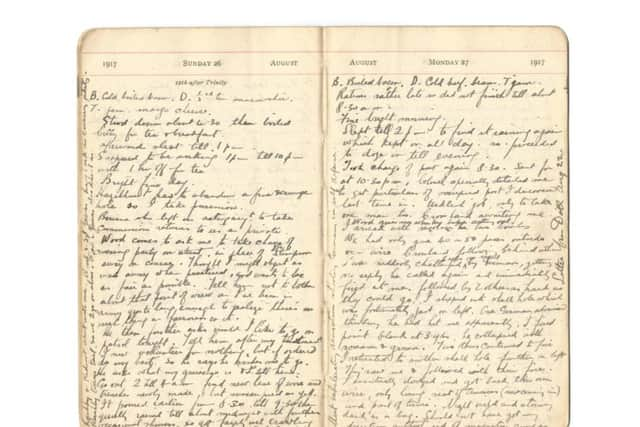

August 27 1917

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe colonel specially detailed me to get particulars of the occupied posts. A ticklish job. I was only to take one man with me. I arrived with a revolver and two bombs. We’d only gone 40 or 50 paces out when I was challenged by a German. He immediately fired at me followed by two others. I slipped into a shell hole.

One German advanced, thinking that he’d hit me. I fired point blank at three yards. He collapsed with groans. The two others continued to fire. I eventually dodged and got back through our wire. The night was dark and stormy. It was the most exhilarating sensation shooting Germans in self-defence.

The Pals’ objective, the village of Serre, remained held by the Germans until they withdrew the following year.

Frank survived the Battle of the Somme, and lived through the Great War. He died in 1935 whilst on holiday with his family, drowning in the sea at Bridlington as a result of a diabetic attack. Son Jim, then aged 10, saw the whole thing and, overwhelmed with grief, barely spoke of his father in the years that followed. It fell to daughter-in-law Penny to read the diaries and transcribe them.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“There’s nobody left now from the First World War. It’s so important to pass the message on. Not just for Frank’s great-grandchildren but for relatives of the people that are mentioned in his diaries. I’m going to Serre on July 1. And I’m taking Frank’s diary back to the trench at John Copse. I will stand there reading what he wrote 100 to the minute that it happened.”

• The Meakin Diaries is published by Austin Macauley Publishers. The Somme: The First 24 Hours is on Discovery UK at 8pm on July 3.