The Partition of India - a story of tragedy and turmoil

By 1947 Britain was exhausted. For though it had emerged victorious from the Second World War victory had come at a high price.

At the start of the century Britain had arguably been the most powerful nation on earth, but now its economy was on its knees and many of its war-ravaged towns and cities needed urgent rebuilding.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdOn top of this it faced growing discontent from within its ailing empire - particularly the Indian subcontinent. Britain had ruled India since the mid-18th century but 70 years ago its colonial rule there was about to come to an end.

The country was split into two independent states - Hindu-majority India and Muslim-majority Pakistan. This momentous event - known as the Partition of India - triggered one of the largest mass migrations in human history as millions of Muslims moved to Pakistan and East Pakistan (now Bangladesh), while millions of Hindus and Sikhs made their way inside India’s new borders.

However, rather than being a peaceful transition sectarian violence erupted particularly in western Punjab, which was cut in two by this arbitrary line, as communities that hitherto had lived together peacefully for centuries turned on one another.

It’s estimated that as many as a million people were killed and tens of thousands of women were abducted and raped. Yet it’s only now, 70 years on, that the full scale of the atrocities is finally coming to light with many people talking about their experiences for the first time.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

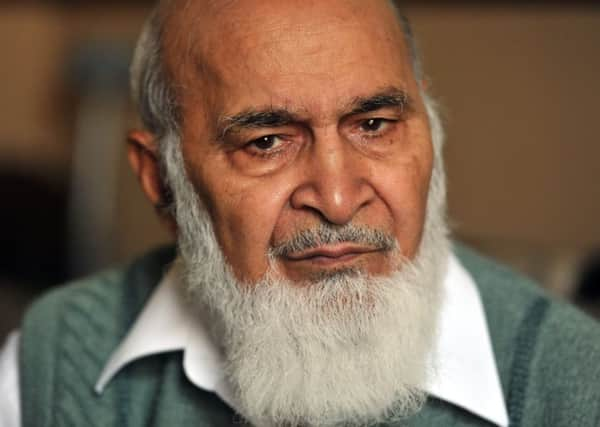

Hide AdJamil Akhtar, 70, arrived in England in 1968 as a student and went on to become a Kirklees councillor and the first Asian magistrate in Huddersfield. He was born in India into a Muslim family and was just four months old when partition came into force.

His parents lived in a village called Therial in Punjab. “All the Muslims living in that part of Punjab had to go to Pakistan. Rumours started spreading very quickly and there was violence and killing going on from all sides. People just changed overnight and in the name of religion they were willing to do anything,” he says.

Jamil’s parents, along with scores of others, made the precarious 150-mile journey to Lahore in Pakistan by foot. “They travelled for about a month and a lot of kids died along the way through starvation. My mother carried me on her shoulders... I was one of the lucky ones who survived.”

However, other members of his family were less fortunate. “My father’s sister and her three sons, her daughter and her mother and father lived in a village about 10 miles from us. They set off from there but they were all killed and thrown in the river, except for one of the sons who somehow survived.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“He managed to get to Pakistan where he told relatives what had happened. He said they were stopped by a group of Sikhs and he told how first they killed the children with their swords, then his parents and his sister and two brothers.”

It’s a shocking story but far from an isolated one. Jamil believes that the British Army, which was still in India at the time, could have done more to prevent the bloodshed. “My father told me that my grandfather begged the British soldiers who were there to stop the killing but they said their instructions were not to intervene.”

Seventy years on and many people feel this dark chapter in human history has largely been overlooked. “It was genocide. More than a million people died but it’s something people tried to forget happened,” says Jamil. “There are no memorials in India or Pakistan and there was never a public inquiry or investigation into what happened.”

Mohammed Hanif Asad’s family was also caught up in the violence of 70 years ago. He was nine years old and living with his family in Lyallpur (now Faisalabad) inside the newly created Pakistani border. But he also had many relatives living on the Indian side of Punjab. “These communities were living together peacefully for thousands of years - Muslims, Hindus and Sikhs,” he says.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“I think it was the media at the time that started spreading hate between the communities and also some politicians who wanted to stir up people’s sentiments for their own use. Old differences between Muslims and non-Muslims became highlighted.”

He says law and order collapsed practically overnight. “The British had controlled this sub-continent for 200 years. They could have waited another six months before leaving to make sure partition was done peacefully, but they left hurriedly because they were tired of wars.

“There was no one to stop people killing one another. The mobs became uncontrollable. One village would decide they were going to attack the next village and they would go and kill the villagers and rape the girls or take them away. Those were dark days.”

His own family suffered. “My auntie lived in a village in India called Saraba and the whole village was slaughtered. She had four sons and one daughter and her daughter was due to be married over on our side but she was taken away and never found.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“My auntie had more than 50 injuries on her body. She had been thrown into the canal and left for dead. She held onto a bush and managed to get out and then a group of refugees passing on carts helped her and brought her to Pakistan.”

Mohammed says his village escaped the bloodshed but he remembers the tense atmosphere. “A railway line ran through our farm where we lived and I remember seeing the trains full of refugees. They were sitting on top of the carriages and there were soldiers to protect them from attack.”

Elsewhere, the sectarian violence saw friends and neighbours turn on one another. “In many places the girls thought they were going to be raped and in those days there was a well in the centre of the villages and they threw themselves in the well to commit suicide.”

Those who could left and made their way to makeshift refugee camps, or fled and made their way to the other side of the border to stay with relatives. “Our communities should have apologised to one another for the atrocities committed against people who were living in the same villages and living on the same land for centuries.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdMohammed has lived in West Yorkshire since 1961 having moved here to start a new life with his family, and while many people couldn’t bring themselves to talk about their harrowing memories he believes it’s important that as many stories are heard as possible.

“Most of the people who saw what happened have passed away and now there are very few of them left. That is why it is important that people do not succumb to hate propaganda again, because it was hatred that incited these terrible things.

“Hatred can spread quickly at any time against a community but we must not allow it to happen.”

The impact of partition in India

At midnight on August 14, 1947, British India, as it was then known, was divided along religious lines, creating the two independent states of India and Pakistan.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdWhile the handover of power had initially been scheduled for the summer of 1948 it was brought forward 12 months by the last viceroy Lord Louis Mountbatten, who took just three weeks to declare the new border - known as the Radcliffe Line - up and running.

With no time to absorb the change, overnight Muslim and Hindu families found themselves on the wrong side of the division.

Between 10 and 12 million people were displaced as a result, triggering a huge refugee crisis as well as large-scale violence that claimed as many as a million lives.