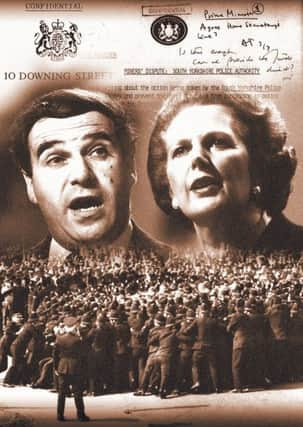

Tom Richmond: Orgreave memo shows need for truth about a dark hour for a divided nation

The date is July 3, 1984. The country is still reeling from the violent exchanges outside the plant the previous month and Leon Brittan – the then Home Secretary and Richmond MP – has sent a three-page briefing document to the PM explaining how Peter Wright, the embattled force’s Chief Constable, had been forbidden by Labour-controlled South Yorkshire Police Authority from incurring any costs policing the picket lines outside Orgreave without “their express authority”.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdProposing that the Government bypasses the police authority, and South Yorkshire County Council, by making emergency funding available, Mr Brittan concludes: “I am sure we need to move quickly in this way, to forestall public speculation that police operations against the dispute will be hampered, or even that the Armed Forces would have to be brought in instead.” Typed on the Home Secretary’s official headed paper, he signed the letter with his initials L.B.

Sent to 10 Downing Street, it was received by Andrew Turnbull – Mrs Thatcher’s private secretary – who studied the contents and wrote at the very top: “Prime Minister. Agree with Home Secretary’s line?” The words “Prime Minister” are underlined for emphasis and it is signed “AT 3/7” before being placed in a red box for the Tory leader to peruse later that same evening in her Downing Street study.

She clearly did. Before returning the Brittan memo to Mr Turnbull the following morning, Mrs Thatcher wrote on the correspondence in her own unmistakable handwriting: “Is this enough. Can we provide the funds direct?” These remarks are signed “MT”.

This is re-enforced by the letter that Mr Turnbull then wrote to Hugh Taylor who was Mr Brittan’s private secretary at the Home Office. It began: “The Prime Minister has seen the Home Secretary’s minute of 3 July. She agrees that the Chief Constable of South Yorkshire should be given every support in his efforts to uphold the law.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThough many will be sympathetic to Mrs Thatcher’s steadfast insistence that the “rule of the mob” must not supplant “the rule of law”, a fresh inquiry is now integral to South Yorkshire Police’s attempts to draw a line under those corrosive controversies, past and present, which have been so damaging to its reputation.

With The Yorkshire Post revealing last week suspected links between the police’s handling of the Orgreave aftermath, and the tragic events at Sheffield Wednesday’s Hillsborough five years later when 96 Liverpool football fans were unlawfully killed in Britain’s worst ever sporting disaster, Mrs May is under mounting pressure to release all Orgreave documents. She should not hesitate to do so.

Of course, the clock cannot be turned back, but total transparency will help to shed new light on the reasons why prosecutions against picketing miners at Orgreave collapsed because of unreliable evidence and any communication at the time between the Thatcher government and police force.

After all, these momentous events preceded the advent of 24-hour news channels so Ministers in London were either getting their information from edited packages on the evening news, the print media (a clipping from The Yorkshire Post of South Yorkshire Police Authority’s deliberations featured in the aforementioned Brittan memo) or briefings from police chiefs and others.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdDocuments preserved by the Margaret Thatcher Foundation certainly highlight the then PM’s determination not to surrender to the miners and trade unionists. They also paint a vivid picture of a country at war with itself.

As the miners’ dispute escalated, Mrs Thatcher went on a walkabout at the cattle market in the Oxfordshire town of Banbury on May 30 when she told onlookers that “the rule of the mob” would not prevail “because of the magnificent police force well trained for carrying out their duties bravely and impartially”. These remarks were evidently greeted by loud cheers. The bravery of the police, and their re-enforcements, is accepted, but how did Mrs Thatcher come to the view that the police were acting “impartially”. Was this taken on trust – this was an era when the integrity of police chiefs was rarely called into question – or from official briefings? Even with the passage of time, this question remains a tantalising one, not least because the police’s operational order for Orgreave, setting out the parameters for patrolling the picket lines, has never been published.

On the day after the so-called Battle of Orgreave on June 18, 1984, Mrs Thatcher struck a defiant tone at Prime Minister’s Questions.

In words that could only be heard – and not seen – because they preceded the televising of Parliament, Mrs Thatcher is recorded as saying that the “violent tactics” were not working at Orgreave. “They have failed. The lorries got through, the coal is getting through.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIn subsequent exchanges indicative of the highly-charged political battle lines at the time, Tory MP Cranley Onslow, who represented Woking in Surrey, referred to “disorders at Orgreave and elsewhere” and sought “criminal charges against those responsible for controlling and directing these riotous mobs”.

The very next question saw Martin Redmond, the then Don Valley MP, ask: “Will the Prime Minister inform the House when she has sufficient blood on her hands to satisfy her hatred of the miners?”

The Tory leader dismissed this but the defiant language used by the Prime Minister does prompt one to consider whether South Yorkshire Police – on the frontline of a year-long dispute to determine whether the Tories or trade unions governed Britain – did conclude, erroneously, that it had sufficient political cover to take short cuts with the criminal process?

A profound question then, it is equally profound today because of the extent to which Yorkshire’s one-time mining communities feel betrayed by their police force and those officers drafted in from around Britain. Did 10 Downing Street and South Yorkshire Police believe that any communication and correspondence would never be disclosed? After all, this period in history came at a time when the Official Secrets Act was sacrosanct and classified material could not be released for 30 years. Now Freedom of Information laws have transformed political transparency in this country.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdTwo weeks before the Battle of Orgreave, the aforementioned Mr Turnbull – now a House of Lords peer – wrote a confidential memo to Mrs Thatcher which talked about the then British Steel Corporation taking civil action to stop the pickets. Reference is made to a meeting attended by Norman Tebbit, the then Trade Secretary.

“You raised the question of whether it was right “to leave the police in the firing line” while no action was being taken in the civil courts. The key question is whether, apart from moral support, the police would be any less in the firing line,” wrote Mr Turnbull.

And, on the day after the Orgreave riot, Mr Turnbull received a two page letter – marked “secret” at the top – from Energy Secretary Peter Walker’s private secretary Michael Reidy talking about contingency plans to remove sufficient stock from Orgreave so Scunthorpe’s steel plant could continue to operate.

“It was further agreed that British Steel would immediately write to the Chief Constable of South Yorkshire to inform them of their plans to empty the Orgreave site,” wrote Mr Reidy. “The police would then, as necessary, be in a position to demonstrate that they were part of a carefully conceived and well-executed operation.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdMarked “File” in pencil, it is one of six copies. The other five recipients are unknown.

Yet such disclosures come back to that one recurring question: Did the tone of such correspondence, and the political backdrop to the Miners’ Strike, lead some in South Yorkshire Police – a force that could do no wrong according to Margaret Thatcher and senior Ministers – to conclude that it had the power to circumvent the law at Orgreave, and then Hillsborough with desperately tragic consequences five years later, in the gravest miscarriage of justice of all?

It is a question that should not be left unanswered any longer. Three decades on, total transparency is a prerequisite to the South Yorkshire force, and wider police profession, winning back lost public trust.