Nostalgia on Tuesday: Hall's glory days

In the latter category were death duties and by the early 20th century these weighed heavily on a deceased squire or lady’s dependents. Such was the case at Sprotbrough Hall, South Yorkshire, where an extraordinary sequence of events took place in the 1920s.

Under the stark headline Death Separates and Reunites – Sprotbrough Squire and Lady Die within Four Days, the Doncaster Gazette, June 29, 1923, sensationally reported the deaths at the Hall of both Brigadier-General Sir Alington Bewicke-Copley and his wife Lady Bewicke-Copley.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdLady Bewicke-Copley died on the day of her late husband’s funeral. General Bewicke-Copley, it was understood, had been suffering from bronchial trouble for a few days, and attended a Yorkshire cricket match at Sheffield, where he caught a severe cold, and pneumonia rapidly developed. Her ladyship, who was 67, appears to have contracted the complaint while nursing him.

The couple’s son, Robert Wolseley Bewicke-Copley, took control of the hall and estate but this was short-lived, as they were subsequently sold to meet heavy death duties. The hall, together with a large part of the richly wooded estate, was bought by F S Gowland, a member of a firm of Ripon solicitors, for £5,100.

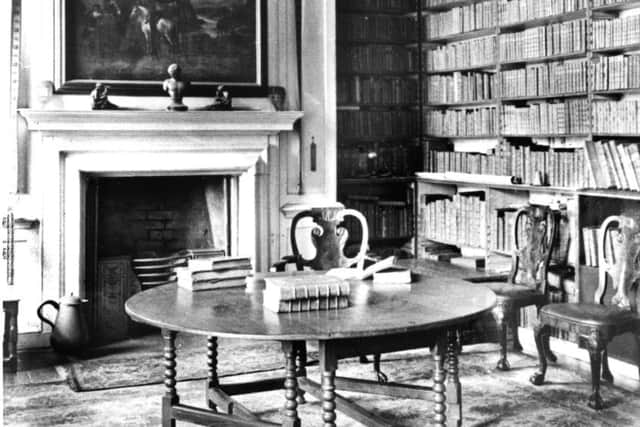

Its contents were sold in October 1925 and among the treasures were over 60 pictures including works by Rembrandt, Raphael and Van Dyck. The library’s contents were sold at Sotherby’s and this yielded a first-edition copy of Paradise Lost, 1667, bought for £270.

By mid April in 1926, newspapers were reporting the demolition of the property was under way.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdOf course many interesting accounts linger about a demolished house’s former splendour, its contents and occupants. Sprotbrough Hall is no exception and much is to be recalled about the builder Sir Godfrey Copley, 2nd Baronet (1653-1709). He was the son of Sir Godfrey Copley (1623-1677) who was created baronet by King Charles II in 1661, and he succeeded to his father’s titles and estates in 1678.

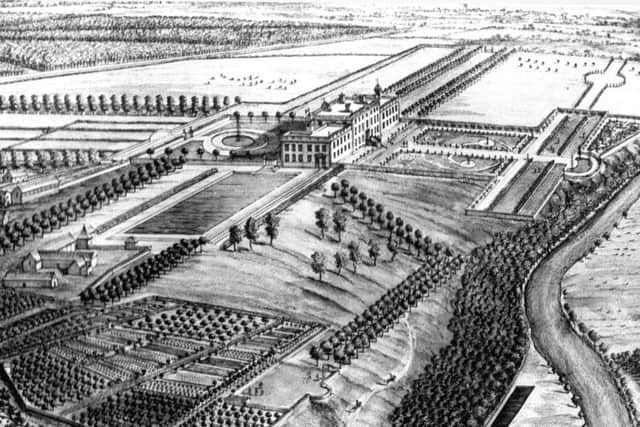

Built around 1685, Sprotbrough Hall sat comfortably amid formal gardens in the Dutch and French style, commanding a wide view of the surrounding countryside.

Country Life of February 11, 1922, comments on the Hall’s style: “The tradition that the house is a copy of a wing of Versailles cannot be corroborated by fact. No doubt Versailles brought home to the Yorkshireman’s mind the grandeur of that style but when he returned from his Grand Tour to his native little country, little more than a vague impressions would seem to have remained with him. These confused with English Carolean tradition, combined to produce Sprotbrough Hall.”

The building was erected from local limestone. The ground floor contained a dining room,and ante-room, library, drawing room, music room, boudoir and a gun room. The first floor included 11 principal bed and dressing rooms, the second floor 14 bedrooms.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdSir Godfrey was MP for Aldborough from 1678 to 1681. He was again elected to Parliament, this time for Thirsk, in 1695. Apart from politics, he also found time to pursue his interest in hydrostatics, constructing a magnificent ornamental fountain in Sprotbrough Hall’s grounds in about 1703. This followed a visit to the Duke of Devonshire’s Chatsworth House where an Emperor Fountain boasted a 290ft jet. At that time it was the second highest in the world. Despite engineering difficulties, Sir Godfrey was determined to produce a fountain comparable with that at Chatsworth.

He designed a method of raising the water 150 feet from a low near the river Don to a tank on the flat roof of Sprotbrough Hall. He was assisted in the project by George Sorocold, an eminent engineer who was much in demand for building waterworks for a number of towns and cities.

Sir Godfrey’s hydrostatic improvements around the Sprotbrough estate led to one material comfort being added to the hall – a bath. The extent to which he enjoyed this can be gathered from a letter sent to a friend on September 3, 1707, and published in Notes and Records of the Royal Society of London.

Sir Godfrey wrote: ‘I have succeeded past my expectation in making such a bath for pleasure and convenience as I think no one in this kingdom hath ye like. It is between 34 and 35 foot long and about 16 foot broad with a convenient pair of stairs to go down and sides lined with lead and holds water six foot and four inches deep. Two or three faggots and a sack of coales doth warm it equal to ye heat of your body but we can make it hotter if we please. I have never met with a bath more agreeable’.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdWhen he died in 1709 he left a bequest of £100 to the Royal Society. This provided funding for an annual award, the Copley Medal, the Society’s premier award for scientific achievement. It is Britain’s oldest scientific honour, a prestigious forerunner of the Nobel Prize.

There followed a succession of Copleys at Sprotbrough.The estate, including two villages, was eventually sold in 160 lots during 1925. The Doncaster Gazette reported: ‘Sprotbrough Hall estate, now a wilderness, ready for the miscellaneous builders’ heaps that inevitably precede the erection of houses, will soon be nought but a memory to those who have lived within a stone’s throw of the once stately old country residence recently demolished.’

Today, the only visible remains of structures, once in the immediate vicinity of the hall, include a balustrade facing the river, a stable block (now converted for housing) and stonework once forming part of the engine house feeding water to Sir Godfrey’s fountain.

Thanks to Hugh Parkin for help with this piece.