Back to the roots of British folk clubs

Julian Bean called in at The Greystones the other day. The pub is up a steep hill just outside Sheffield city centre and is worth the climb – local beer, food, fashionable bare wood floors and, most distinctive of all, live music nightly.

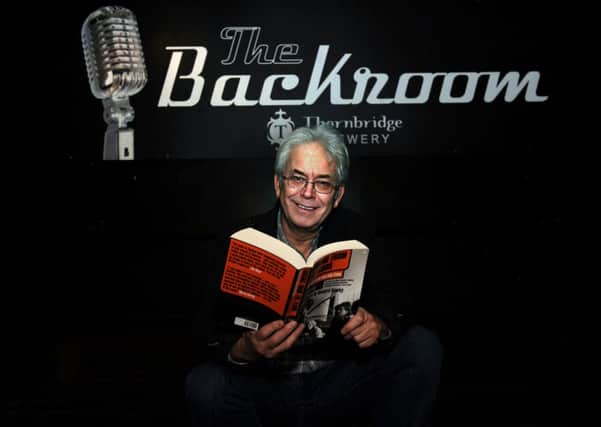

In a large space at the rear, The Backroom, they have a top musical set-up with an international programme six nights a week. Luminaries like Richard Hawley, Sheffield’s favourite singer-songwriter, feature on the old gig posters plastered on the walls.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe pub was not like this when Julian Bean first dropped by as a teenager. Then it was the Highcliffe Hotel and home to a folk and blues club started by a local schoolteacher, Win White. It opened in 1967, one of numerous such clubs which had been popping up all over the country since the mid-50s, lifted by a tide of interest among urban youngsters like Julian.

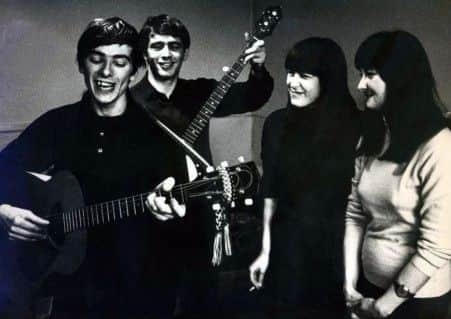

His first intoxicating folkie experience was on a Saturday night in 1966. Aged 16 he rolled up at the Barley Mow above the Three Cranes pub in Sheffield and with 140 others squeezed into an L-shaped room large enough for 40.

It was a life-changing experience, one which untold numbers of young people were joyfully embracing in overcrowded dives up and down the land. “It was a world of upstairs rooms, beeriness and cheeriness,” recalls Julian who says every Saturday night at the Barley Mow seemed like Christmas Eve.

Within a couple of months he had seen Ewan MacColl and Peggy Seeger perform there. Up at the Highcliffe Hotel, Ralph McTell was a regular club guest and they also gave an English debut to a Glasgow shipyard welder and banjo player, unknown south of the border, called Billy Connolly.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdNow fast forward 40 years. Julian, who has kept up with the folk scene, decides a comprehensive account of British folk clubs needs to be written before the memories of those who performed in them are lost. So he sets out on a four-year odyssey around the country to pin down as many key figures as possible for face-to-face interview and get their stories down on tape. There’s no incentive for Julian by way of a commission from a publisher. He just does it on spec.

“It was a bit barmy really, madness,” he says.

It was a huge undertaking, 140 interviews conducted all told, some of them four-and-half hours long. The tapes now occupy sundry shoeboxes stashed under the interviewer’s bed.

The end product of all the commitment and the hard miles travelled is a real achievement. Some might expect to find here a definitive catalogue of trainspotter-style scholarship, a work of consuming interest for fellow enthusiasts, but maybe not a book for a wider audience.

The opposite is the case. It’s a real page-turner. The only times when it isn’t may be when the reader is too limp with laughing to continue.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdBean pulls it off by keeping the authorial voice mostly out of the pages and leaving the stage to the performers. He skilfully snips each first-hand account into pieces and then gives them a thematic re-working. The voices are juxtaposed to give an impression of conversations.

Differing views and judgments are aired about, let’s say, the rise of an influential institution like the Singers’ Club, or the impact of significant artists like Ewan MacColl and Peggy Seeger. Sometimes the voices are friendly, sometimes hostile, salty or scathing. They are invariably compelling, coming as the do from people whose talents usually include a sharp eye for the significant detail.

The performers’ passion and dedication shines through and their anecdotes capture the flavour of the fun and also the hardship of long nights on the road with little money for creature comforts. They earned maybe £10-£15 for a gig and their relish for the job seems undiminished by the passing of time.

“I travelled all over the country and yes, it could have been dangerous…when I had young children and travelled back on overnight trains,” says Shirley Collins, who had her first breakthrough in 1964 and is now president of the English Folk Dance and Song Society.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“Some of those trains were grim and unnerving. At least some of my fellow passengers were. But I survived. I had a hot temper and a heavy banjo case for emergencies. Looking back, I wonder why I put myself through it. But I suppose it was because I had to sing.”

Her response recalls something I once heard from Norma Waterson on the radio. Norma was explaining that she had not grown up with this sort of music but the first time she heard an English folk song and tried to sing it, “it felt like coming home”.

Julian found some artists trickier to bring to his tape recorder than others. “I spent 21 months trying to get Billy Connolly,” he says. “It was like knocking on a steel door. Then one day I got a phone call saying Billy will be at a certain hotel in Bawtry tomorrow. I had two hours with him, sitting and drinking tea and talking over the old days – I’d seen him play at the Highcliffe. He’s never lost his enthusiasm for that. No one I approached gave me short shrift.”

One contact would lead to another. So a chat with Eliza Carthy was followed by a subsequent text message from her saying uncle Mike was happy to talk to him. Julian promptly took his tape recorder up to a stricken Mike Waterson who spoke to him six weeks before he died.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe Watersons – Mike, sisters Norma and Lal and their cousin John Harrison – came from Hull and opened one of the first folk clubs there in the 50s in the Baker Street Dance Hall. In 1973 Norma married Martin Carthy, who lives at Robin Hood’s Bay and who last month received a lifetime achievement award in the BBC Radio 2 Folk Awards. The family are the closest you’ll get to folk royalty.

Folk is a broad church with many strands but one central conviction for its adherents: the music is what they believe in. At one time, possibly the word of praise a folkie sought most was ‘authentic’. As the evangelists saw it, authenticity was the opposite of the commodified, commercial music thoughtlessly consumed by the masses. High-mindedness however could be a folkie’s weakness.

The overbearing nature of certain key artists was not to Shirley Collins’ taste, for example. “I particularly disliked and distrusted the pretentious and arrogant way that Ewan (MacColl) performed,” she says. MacColl, despite a name resonant of Shetland crofters or the Highlands, was actually Jimmy Miller from Manchester.

Political ideology often played a part at the beginning. When, in September 1956, a Communist Party member called Alex Eaton opened the Topic folk club in Bradford, the police, sniffing sedition among the singers, raided it.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdJulian Bean reckons this is about the time when the term ‘folk club’ first came into general usage. A magazine in 1961 put the total number of clubs in the country at 36. Martin Carthy says he saw a survey just nine years later that indicated there were 400 of them in London alone.

Bob Dylan and Paul Simon put in an appearance on this first underground or alternative scene, neither agreed to speak to Julian about it. Instead he tracks down the man responsible for bringing Dylan to England, a former BBC TV drama director called Philip Saville, who is eventually persuaded to have a chat.

The obscure Dylan was working at the time at the Gaslight Café among others in Greenwich Village which features in the new Coen brothers film, Inside Llewyn Davis, about the early 60s New York folk scene. Philip Saville saw Dylan there and rather quixotically cast him in a BBC television play called Madhouse on Castle Street being made in London.

The story of what happened when a soon-to-be anointed music superstar was found to have no talent whatsoever as an actor is fascinating.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdPaul Simon was a more permanent presence and his trail is followed, via an interview with Tom Paxman, to a flat in south Kensington where unglamorous nights were spent by the two flatmates playing Monopoly.

Simon was struggling to get his foot in the door and offered his services to Brentwood Folk Club for £5 a week. The club weren’t sure but took him on after consulting Martin Carthy who thought that if the job seeker was American he might be ok because American kids were taught proper folk songs at school.

The trail heads north to Lancashire. According to legend, Paul Simon wrote his hit Homeward Bound during a long wait on a railway station platform at Widnes after a folk club gig. Julian Bean discovers the real story. He interviews Simon’s host during the time he stayed in the area and he reports that he drove the singer to the station for his return rail journey and they arrived only just in time to catch the train.

Having collected his material, Julian persuaded Richard Hawley to contribute a foreword. And Hawley, a former member of the rock band Pulp, also offered to bring the manuscript to the attention of the band’s main luminary and fellow Sheffielder, Jarvis Cocker, in the light of Cocker having been appointed to the title of ‘editor-at-large’ for the publishers Faber & Faber. The book was to be Cocker’s first acquisition for Faber.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe timing is pretty good too. The death of Pete Seeger last month focused fresh attention on the roots of folk and its social and political impact. The Coen brothers’ movie plus the award to Martin Carthy have probably made people more receptive to this sort of book.

Today folk clubs may not be quite what they were, although the Topic in Bradford remains as the UK’s longest continuously operating folk club and there are many others soldiering on.

Arguably interest in this sort of music is higher than ever, although what you would call folk is perhaps more broadly defined than was in the early days.

Performers have found that paid niches have expanded to accommodate them in pub bars and the growth of festivals that welcome folk music of one sort or another has been extraordinary.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAnd at places like The Greystones, the inclusive impulse lives on. One night a week is dedicated to giving anyone a chance to come along and sing.

• Singing from the Floor: a history of British folk clubs by JP Bean. Faber & Faber £17.99. Julian Bean will be talking about his book at Waterstones in Orchard Square, Sheffield at 6.30pm on April 2.