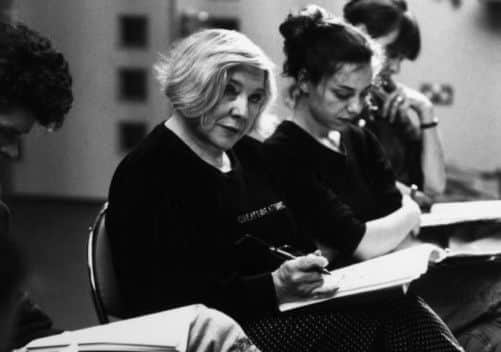

The Big Interview: Fay Weldon

Fay Weldon is one of life’s gigglers. She has this girlish, airy-fairy voice that’s always on the cusp of laughter, ready to give full vent at the slightest excuse.

She launches into a sentence, then a wave of mirth can erase the end of it. You sometimes just have to get the gist. All of this can make what she’s actually says sound fanciful. Mind you, she has admitted in the past that a sizeable chunk of what she says to journalists has more to do with whimsy than truth. She likes to amuse herself.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdShe’s just turned 82, and shows no signs of hanging up her quill nor her merry attitude to life. It’s all potential copy to her, and some of the dramatic episodes in her older novels, which charted the vicissitudes of women in modern times with a wit that was often savage, are influenced by (but not necessarily based on) her own experience.

The Fat Woman’s Joke, Female Friends, Praxis, Puffball and The Life and Loves Of A She-Devil portrayed women who chafed against the straitjacket of their lives, didn’t necessarily love their children and took some pretty desperate measures to escape their situation.

The author of 34 novels, several collections of short stories, many radio and stage plays, innumerable pieces of journalism and essays, Weldon still turns out a book a year from her study at home atop a windy hill in Dorset.

She has four sons, step children, seven grandchildren – but says she’s not a model grandparent – and bats on with her busy working life aided by two new knees. One, the right one, is an older, titanium model. The other, only three years old, is made of lightweight nylon. Both have played their part in putting their owner back on her feet relatively painlessly. After the last op she was back at her desk in days and at church (following decades as an agnostic she was baptised into the Anglican Church about 10 years ago) having missed only one service.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdEver the writer, Weldon kept a diary of her thoughts and feelings before and after the last knee op, and the ensuing article appeared in Saga Magazine. Now she’s a sort of poster girl for how an alien spare part can give you renewed energy and purpose.

She says that, compared to gall stones, childbirth and frozen shoulder, knee replacement is a breeze. “And you get to show off your neat little scar to anyone too polite to say no,” she says, with a little burst of laughter.

Her tendency to laugh suggests she might have been the ringleader in rather a lot of mischief long ago at South Hampstead High School, where she was a scholarship girl.

Born in Birmingham to a literary family – her grandfather Edgar Jepson was a writer, and her mother Margaret published novels under a pseudonym – Fay Weldon’s family emigrated to New Zealand when she was very young. When her parents’ marriage broke up, Fay and her mother and sister travelled back to England by ship, arriving on her 15th birthday. Her mother had to work to support the family, and got a job as a housekeeper in London.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“She was a brave and very valiant woman,” says Fay. “She had become a very successful novelist in New Zealand and writing had changed her life. But when we got back to England and were penniless, she had to do what she could to earn money straight away and never returned to writing.”

Fay’s memories of living in at a smart London address in the late 1940s while her mother ran the household are of darkness and bars on the windows in the lower parts of the house where “the help” lived.

However, the happy-go-lucky Fay didn’t feel disadvantaged among the children of some of the North London literati at school, and she was consistently near the top of her class before moving on to study psychology and economics at St Andrews.

After getting pregnant and delivering a son at 22, she returned to London and married a headmaster 25 years her senior who was not the child’s biological father. They divorced when she left a couple of years later. In order to support herself and her son, Weldon started working in the advertising industry. She was exceptionally good at it. As head of copywriting for a leading agency at one point she was responsible for publicising (but not actually coining) the phrase “Go to work on an egg” but couldn’t get them to back the slogan “Vodka gets you drunk quicker”.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAt 29 she met jazz musician and antiques dealer Ron Weldon. They married and had three sons, and it was early in this marriage that Fay began to write for radio and TV. Her first novel, The Fat Woman’s Joke, was published in 1967, and in 1971 she wrote the screenplay for the pilot of Upstairs, Downstairs.

“I was pleased and keen to do it because the drama was set at a time when there was great upheaval in British society and great renewal and interest in how the world worked,” she says.

Nearly 40 years were to pass before she returned to writing about the workings of the English upper class and their servants at the turn of the 20th-century. Weldon worked hard, despite four boys and their racket around the house. She describes motherhood and bonding as “a lifetime sentence to anxiety”. Her boys were spaced across 25 years, and she had a succession of au pairs, but recalls some severe difficulties in meeting deadlines.

“It helped to have a good strong girl around, but I can remember sitting writing on the stairs, sometimes with a couple of children crawling all over me. The stairs were handy because they could see you were near, without actually being in the room with them. But if they wanted to they could come and find you for reassurance.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdShe thinks one of the reasons behind the development of her trademark style of short sentences and short paragraphs was that she was so often interrupted. “Sometimes you were lucky to get ten minutes’ writing done at one go.”

Ron Weldon was keen on therapy and it was his astrological therapist who advised him that he and Fay were not astrologically compatible. He and the therapist were, apparently, and the 30-year marriage ended. Fay subsequently married Nick Fox, a poet and writer who is also her manager, accountant and minder.

In recent times she has moved away from novels and the odd factual book that in some way deal with making your way as a woman in the world, back to history and the quaking plates of society before the First World War. She’s just publishing The New Countess, the final part in a trilogy about an English dynasty and their servants.

It’s soft stuff compared to her pithy earlier work, but she seems to have enjoyed describing costumes and decor, the saving of the family fortunes thanks to an American heiress, and the readying of the family’s country seat for a visit by the King and his mistress. The most interesting character is Rozina, the daughter who marries for love and is then liberated in many different ways by widowhood.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdFay Weldon “doesn’t care at all” that her work has never won big literary prizes, and says she has judged enough prizes to know that “the most boring book with no jokes” will win. After decades of having her work associated with feminism, she brought opprobrium down on her own head by saying that there were worse things than rape for a woman – such as death.

She weathered that storm, then went on to opine – years ahead of anyone else – that men were the new victims of the gender war.“In the 70s men were behaving badly (towards women), but they have improved. As more women went out to work and carved out careers, men became more put-upon and a bit downtrodden. But now the balance is better.”

Do we still need feminism? “We do, in the sense that the price of freedom is eternal vigilance, but I think the greatest use of feminism now is to look beyond ourselves in our society to those countries where women don’t have the liberty we enjoy.

“Women in this country have most freedoms, except the freedom to work (or not). In general women are getting better at recognising that men are people too – although some still don’t believe it.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHas disapproval ever bothered her? This evokes an unexpected giggle.

“Everyone wants to be liked, but you have to stand by what you really think.”

She finds time to be professor of creative writing at Bath Spa University.

Her approach is no-nonsense: “You can’t teach courage and you can’t teach what to think. You can teach them that they must not be frightened of upsetting people.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“Of course you have to know your craft extremely well by doing it every day... and you have a duty to your reader not to bore them.”

The New Countess by Fay Weldon is published on November 7 by Head of Zeus, £14.99. Fay Weldon will be special guest at the inaugural Harrogate History Festival, and will talk about her work at 11.30am on Saturday, November 26 at the Old Swan Hotel.

The Festival runs from October 25-27, and other guests include novelists Kate Mosse, Rose Tremain and Lindsey Davis. 01423 562303, www.harrogateinternationalfestivals.com/history.