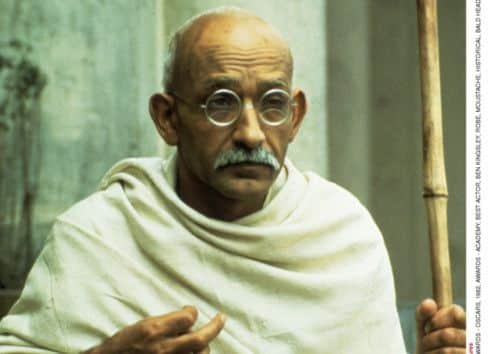

The Big Interview: Sir Ben Kingsley

Sir Ben Kingsley is ruminating on the nature of screen villainy and the eternal question of whether Englishmen make the best bad guys. “Classic villains have a great sense of righteousness and destiny.”

And in a 30-year screen career that rocketed into life with Gandhi his life has been dominated by extreme shades of dark and light.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdFrom the Mahatma to silent movie pioneer Georges Méliès by way of gangster Meyer Lansky, the monstrous Don Logan of Sexy Beast and now terrorist kingpin The Mandarin in Iron Man 3, Kingsley has brought purity to his screen heavies and heroes.

Like Laurence Olivier, who found it hard to play peasants, preferring kings and princes, Kingsley doesn’t do ordinary. Even Itzhak Stern, the right-hand man to Liam Neeson’s armaments magnate in Schindler’s List, is extraordinary in his ordinariness. Kingsley can’t help it.

Now, pushing 70, Kingsley is at the heart of the current fashion for brash, cacophonous, eye-popping comic strip extravaganzas, bringing his own brand of precision to bear on a timeless tale of good versus evil.

“Drama has to be the light and shade, braided together and pulled really tight,” he says. “This is what is lovely about this franchise. There is always a really threatening dark moment and then a moment of tenderness and vulnerability or comradeship, irony, wit, self-deprecation.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“Richard III begins by saying [to the audience] ‘This is all wrong and I am going to sort it out. Stay with me’. In Sexy Beast, my Don Logan was an abused child who was never held and went on to abuse others. That was my key into Don. And I think our Mandarin has to have a profound sense of right.

“What I have to do as an actor is push the ‘villain’ word right to the back and bring forward, however distorted, their absolute sense of right and sense of destiny, which the mandarin had to have throughout. A deep seriousness and dedication to his cause. And it must become the world’s cause.”

Kingsley’s watchwords have been seriousness and dedication. An actor since the early ‘60s, he is proud to say he has never earned a farthing in any other occupation.

He was 20 when he successfully auditioned for Theatre in Education. From there he entered the waning world of repertory before moving on to Chichester. Finally there was the Royal Shakespeare Company. “I am deeply fortunate,” he muses. “I have never turned my hand to anything for monetary gain, other than pretending to be somebody else.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe son of a Kenya-born Gujarati doctor and an illegitimate Russian/Jewish mother he was born Krishna Bhanji in Snainton, near Scarborough, on New Year’s Eve, 1943. The family later moved to Manchester. It was expected that he would follow his father’s profession but there was never any real risk of that.

For years he was reticent to discuss his childhood and the choices he made later as a young man. When his mother died, aged 96, three years ago, the floodgates opened.

“It’s very difficult to be objective about one’s childhood and childhood experiences,” he says robustly. “You have no perspective on it, whatsoever. It was my childhood and I have nothing to compare it with. The only way I can lead a comparative life is to portray other men. In earning my money pretending to be someone else, it has stamped me with what the actor is: tribally central and totally peripheral.

“I enjoy this status so much, feeling that I’m close to the heart of the tribe, whatever that means, as an actor and a storyteller and a troubadour, but socially quite distant, because I don’t fit into any comfortable slots. There’s always a part of me that is migrating.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHe was a late starter in film. Notwithstanding a supporting role in the 1972 thriller Fear is the Key, it would be another ten years before he made his significant debut, aged 38, in Richard Attenborough’s mighty epic Gandhi.

In the years since he has skipped between light and dark with ease. He was Nazi hunter Simon Wiesenthal in Murderers Among Us and the South American torturer in Death and the Maiden. He played Moses and will soon portray Herod. He has been Fagin and Merlin, Sweeney Todd and Dr. Watson. But always the conversation comes back to Gandhi and the role that won him an Academy Award.

“Certainly it is an absolute fact that was the golden key to that gate through which I walked into the film industry after 15 years in the theatre,” he says of that long-ago breakthrough. “I am eternally grateful for that. Everything comes from that.”

Does he ever wonder what his life would have been like had he never played the Mahatma? Kingsley doesn’t miss a beat.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“The only thought I have about Gandhi [and my career] is a story I concocted where I was walking down the street and my friend said ‘See that man over there? That is the man who played Gandhi’. I thought, ‘Thank God it was me’. Thank God it has never happened and that I have never had to look at another portrait of him other than the one that Richard Attenborough and I and Jack Briley created.”

Kingsley’s single-minded pursuit of his calling – “I’m completely in love with film and the minimalism it produces” – has garlanded him with awards. He has one Oscar to his credit and was nominated again for Bugsy, Sexy Beast and House of Sand and Fog. He has a BAFTA and a Golden Globe (plus four more nominations) and a quartet of Emmy nominations, too.

Yet the thrill of winning the Oscar pales when compared with being knighted in 2002. “I was in mild shock on both occasions,” he recalls when asked which meant most. “From when John Travolta read my name out [to] going to receive [the Oscar], I can’t remember a thing. I do believe Her Majesty used the sword which her father used when he was Commander in Chief of our armed forces during World War II. To see that sword move over my head was absolutely thrilling and beautiful.”

He adds: “It is quite hard to separate the two because I think they are connected. It is all part of having a blessed journey. It did feel there was a difference between the two. One is from your peer group and the other is from your nation, which I love deeply.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“The Brits are quite reticent about praising you. They don’t go barmy with enthusiasm so one wonders, being a Brit actor, if anyone has ever noticed what we’re doing. Then you get this extraordinary embrace saying ‘We have seen you. We have heard you’. It’s completely overwhelming.”

Kingsley has said he will not return to the stage. Instead he has half a dozen movies slated for release including Ender’s Game, a chunky slice of sci-fi co-starring Harrison Ford. Kingsley plays Mazar, an ancient warrior-cum-teacher who sports Maori tattoos on his face.

He calls it “quite different from the challenge of the Mandarin” and hints at the level of special effects to be achieved by computers. “With Mandarin I was very rarely involved in green screen. In Gandhi we had none. We actually had 4,000 people on screen for the funeral. In Ender’s Game we had a lot.”

In between Iron Man 3 and Ender’s Game are the WWII Nazi drama Walking with the Enemy, the 11th century period adventure The Physician, the animated monsters of The Boxtrolls and a modern-day version of Ibsen’s A Doll’s House.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIt’s a varied slate. Kingsley’s response is straightforward. “I am at the mercy of what arrives on the desk, as it were. My wife Daniela and I have a production company. To a certain extent we can create what we want to put on the screen. Aside from that it is quite a random process.”

Times and movies change. Doesn’t he ever long for a simpler life?

“I am not very good at looking back,” he smiles. “I am very much in the present. You have to be between action and cut.”