Exposing the literary history of England's most famous houses

Towards the end of the tour, Christine Beevers points to a cardboard box on the table in front of us. “Someone got in touch about that a month ago and said we might like it,” she says, and takes the lid off. Inside, looking rather forlorn, is a stuffed Little Owl. Little but literary, as most things are here at Renishaw Hall, on the Sheffield-Derbyshire border.

The 400-year-old house, with its glorious gardens, was the family home of the formidable Sitwell trio of high-born, high-flown writers – Edith, Osbert and Sacheverell – who took London by storm in the Twenties. In its own park (and its own world) up a long drive near the village of Eckington, it will be hosting the first of a new series of literary tours tomorrow.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdSo the owl’s arrival, in its cardboard coffin, turns out to be very timely. “It was a spoof prize which the Sitwells sent to the person who had written the dullest literary work of the year,” says Christine, Renishaw’s archivist, who will be leading the tours.

She unfolds a slip of paper tucked in beside the bird. On it is the name Charles Sewter, an art historian and editor of the prestigious Burlington Magazine. And there’s a poem:

“The candidate the critics rate

Nor fish nor flesh nor fowl

Upon a date receives a crate

Of desiccated owl.”

Isn’t that so typical of the Sitwell siblings’ – indeed the whole family’s – famed eccentricity, I suggest? Christine demurs: “I’d say they were independent-minded. I’d go for quirkiness instead of eccentricity.”

Well, up to a point... The first time I visited Renishaw, about 20 years ago, I was taken round by its then owner, Sir Reresby Sitwell, son of Sacheverell. In a voice as rich as vintage port, he described how his “auntie” (Dame Edith) made “absolutely lethal Martinis”. Puffing a fat cigar, he buffered round an exhibition of pictures by John Piper, an old family friend (“Look at this... Touch of Picasso, Blue Period, Cubism and so on...”).

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHe was expecting a telephone call from a man in London he wanted me to talk to. “Why don’t you go and look at the garden?” he said. “I’ll ring you when he rings and you can scamper back to the house.”

I said I didn’t have a mobile phone. “Oh no, I mean I’ll ring you with this,” he said, picking up a huge brass hand bell and ringing it furiously like a teacher bringing playtime to an end. When he inherited Renishaw, the house’s gain was the music hall’s loss.

Sir Reresby died in 2009 and the house passed to his daughter Alexandra, who has organised four special Sunday tours over the summer as part of a new Literary Trail launched by the Historic Houses Association.

More than 40 of the association’s houses linked to writers or their works are taking part in the trail, including Norton Conyers near Ripon, which reputedly inspired Charlotte Brontë to create Mrs Rochester, the “mad woman in the attic” in Jane Eyre.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdFor its part, Renishaw is sometimes said to have inspired Wragby Hall in Lady Chatterley’s Lover. DH Lawrence probably never set foot in the house – he once turned up on spec, but no-one was at home – though he did visit Montegufoni, the Tuscan castle which the trio’s father, Sir George Sitwell (MP for Scarborough), had bought.

“Frieda, Lawrence’s wife, went round jumping on the beds, which horrified Sir George,” says Christine Beevers.

Edith, looking ghostly-Gothic with her extravagant turbans and ring-encrusted hands, subsequently denounced Lady Chatterley as “a nasty, dirty little book of no literary merit whatsoever”.

Her own work sometimes attracted vicious criticism. In a 1930 Yorkshire Post review, the poet Geoffrey Grigson lambasted her biography of Alexander Pope as “negligible” and full of “manifold inaccuracies” and “absence of original research and shallowness of thought”.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdSeven years earlier, there was a great rumpus at the first public performance of Facade, Edith’s collaboration with the composer William Walton, another family friend. In her wraith-like voice, she recited her poems accompanied by Walton’s often larky music. The headline on one review memorably dismissed the work as “Drivel They Paid to Hear”.

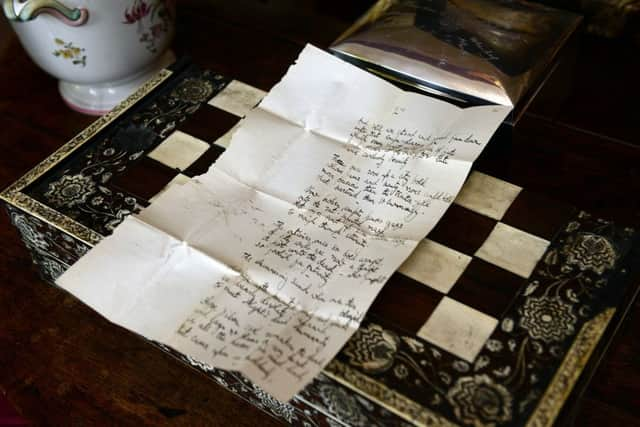

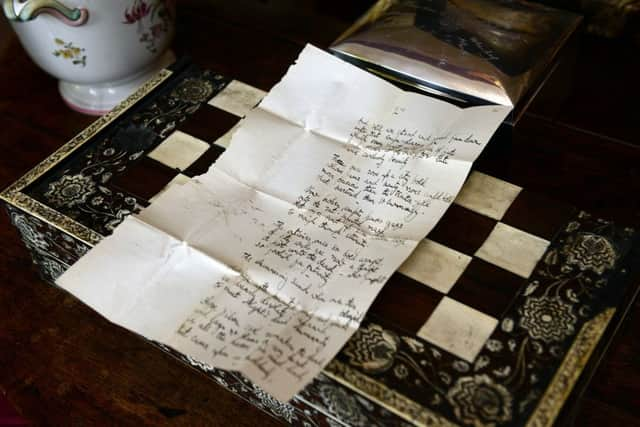

Edith, with what Cecil Beaton described as “eyebrows like tapering mouse-tails”, could give as good as she got. Christine hands over a letter berating the promoters of a later performance of Facade, in which she had taken part.

To get onto the stage, she wrote, “I was told by the porters that I must vault over what looked like 20 drainpipes... in the full view of the audience.”

Worse than that: “The billing of my name in small letters on the advertisement for the concert... was a piece of unbelievable insolence... There is no possible apology you can make me for the gross disrespect with which I have been treated... I will have nothing further to do with any of you and shall read no letter you may write to me.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIt’s a choice item from the 400 sizeable boxes of Sitwell manuscripts, diaries and letters over which Christine presides. Her tours promise tales of Evelyn Waugh, Wilfred Owen, Dylan Thomas, Siegfried Sassoon, and many other luminaries who visited the house or knew the Sitwells (but then, the Sitwells knew everybody).

Mementoes include a childhood lock of “Miss Edith’s hair” and one of her specially printed luggage labels. With every new honorary Doctorate of Letters she was awarded, she added another DLitt after her name. A late label reads: “Dame Edith Sitwell: DBE. DLitt. DLitt. DLitt. Dlitt”, like over-excited birdsong.

There’s a poem about soldiering written by Osbert in the First World War trenches. He sent it to his brother with a note on tissue-thin paper: “I enclose some rot I’ve written.”

Less predictably, there’s a book of knitting patterns. “Edith was a great knitter,” says Christine. “She knitted Alec Guinness a pair of socks and a jumper for John Piper. They were both too big.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdWe tour some of the 60 or so rooms in the house, which was once so cold in winter that Osbert and Edith wore thick overcoats indoors and Reresby and his wife Lady Penelope sometimes retreated to their car to keep warm while they read the papers.

It looks grim, almost prison-like, from the front, but is charm itself at the back, with a garden panorama dominated by a fountain.

Much altered around 1800 by the unimaginatively named Sir Sitwell Sitwell, Renishaw is grand but comfortably homely. “The minute visitors come in, they say: ‘Isn’t this wonderful? A family home!’ People like it because it’s not like one of the big stately homes.”

Few of those, after all, have a hallway guarded by life-sized statues of camp ancient warriors, one wearing a pair of NHS specs left behind by a visitor.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdWhat’s it like, I ask Christine, to be steeped in the Sitwells every day of your working life? “There’s never a dull moment. Whether you call them eccentric or not, they’re very interesting people.”

There’s a danger that the Sitwells will be remembered more for their personalities than their books (Sacheverell alone wrote more than 130). The literary critic Cyril Connolly summed them up: “For all their faults, the Sitwells were a dazzling monument to the English scene. They absolutely enhanced life for us in the Twenties.”

Christine reckons that “apart from the gardens, the trio were Sir George’s most significant achievement.”

Not to be outdone by his children, he was himself an author. His works include Lepers’ Squints, The History of the Fork and Acorns as an Article of Medieval Diet. Eccentric? Not a bit of it.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdLiterary Tours (May 28, June 25, August 13 & September 3) must be booked in advance: 01246 432310; www.renishaw-hall.co.uk. House & gardens open until October 1; Wednesday to Sunday (£6.50 with concessions).