The boy who never grew old

The play premiered in London in December 1904, ran for 145 performances and was subsequently staged annually for many years in front of large audiences.

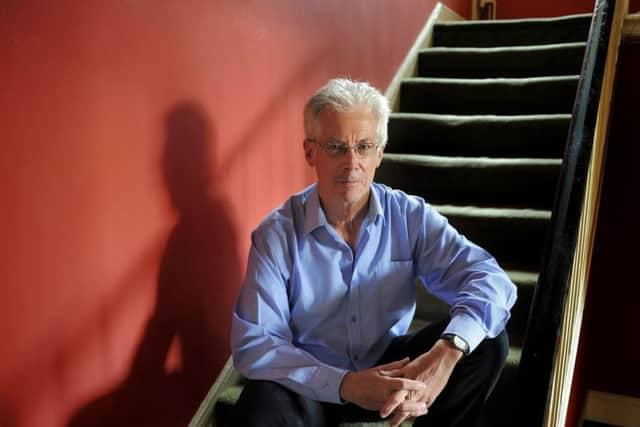

Since then it has been produced regularly on stage, on film and even in dance – Northern Ballet’s production last Christmas was a hugely popular family show. Regent’s Park Open Air Theatre has just completed an acclaimed run of the play transposing it to a First World War setting; Harvey Weinstein’s musical version of the 2004 film Finding Neverland, starring Johnny Depp as Barrie, opened on Broadway earlier this year; and there is a new ITV drama adaptation in the offing starring Paloma Faith as Tinkerbell and Stanley Tucci as Captain Hook. The fascination with Peter Pan continues, speaking to the eternal child in us all. However, the story behind the creation of Barrie’s most captivating and enduring character is quite dark and complex, and one which North Yorkshire author Piers Dudgeon has delved into with his latest book The Real Peter Pan – The Tragic Life of Michael Llewellyn Davies. In it Dudgeon explores the complicated relationship between Barrie and the five Llewellyn Davies boys to whom he became guardian and took into his own home after the death of first their father Arthur in 1907 and then their mother Sylvia Du Maurier in 1910.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdBarrie had befriended the family some years earlier – getting to know the boys before the parents on their trips to Kensington Gardens with their nanny – and as Dudgeon explains in the introduction to his book the boys, and Michael in particular, were to become Barrie’s “gateway to the magical world of childhood, which he longed to recapture”.

The seeds of Dudgeon’s book were sown in 1989 when the author – who has written numerous biographies of novelists including Barbara Taylor Bradford, Catherine Cookson and Maeve Binchy – was working with Daphne Du Maurier on a book about Cornwall, the spirit of the place and how it inspired her novels.

“It was a very successful book but I always felt at the end that we hadn’t really got to the nub of the matter,” he says. “When it was the 100th anniversary of Daphne Du Maurier’s birth in 2007 I contacted her family again and said I would like to do something as I had found that few people had mentioned the Du Maurier family’s connection with JM Barrie.”

Out of Dudgeon’s research came his 2008 book Captivated: JM Barrie, the Du Mauriers and the Dark Side of Neverland. It was a controversial work which apart from highlighting the depth of influence that Daphne Du Maurier’s writer grandfather George had on Barrie and Barrie’s subsequent influence on younger generations of the Du Maurier family, also exposed a side of Barrie that many did not want to see.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“In that book I was the first person to show how important JM Barrie was to Daphne in forming her imagination,” says Dudgeon. “And that led me further into Barrie. Of all the stories connected to him, Michael’s was the most tragic. It is so incredibly sad and in a way it gets to the heart of what Peter Pan is all about. The Llewellyn boys, and Michael in particular, were the muses of JM Barrie.”

In the book, Dudgeon contends that Barrie was a controlling individual who, while ensuring that the boys had every material need looked after, nevertheless seems to have used them for his own means – feeding off their innocent imagination to fuel his own creativity – and in such a way that it affected them all deeply and, in some cases, adversely.

“There was a menace about him,” says Dudgeon. “The five Llewellyn Davies boys all benefited from Barrie’s patronage, but if you actually look at what happened to them, you can begin to dig into this tragic story.”

In 1905, a year after Peter Pan’s extraordinary opening success, Barrie was looking to revise the play with the intention of adding new material which made Neverland – Peter’s realm and home to the lost boys, Tinkerbell, mermaids and pirates – more of a focus. So he summoned the then five-year-old Michael because, as Dudgeon explains in his book “Barrie needed to become a boy again, to re-enter that unconscious, unreflective, mysteriously self-contained mind-set of boyhood”. This meeting provided some of the material for what would become the new Act III of Peter Pan in which Peter and Wendy are marooned on a rock in the mermaids’ lagoon and seem certain to drown. Significantly, given Barrie’s fascination with the afterlife, Peter contemplates drowning, concluding famously that death would be “an awfully big adventure”.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“You can see why the boy started having nightmares and wouldn’t go near water,” says Dudgeon. “I have written about a lot of writers but I have never met anything like this. Barrie took an entire family and consumed it. He wrote not just Peter Pan but other plays where he used Michael – he was part and parcel of the whole process of creation; it’s really unique.”

Throughout his childhood and teenage years Michael was the intense focus of Barrie’s attention, particularly after George, the eldest Llewellyn Davies boy and Barrie’s first key muse, was killed in action in 1915 during the First World War.

“I drew from friends of Michael who knew him when he lived with Barrie,” says Dudgeon. “They felt that Barrie wanted Michael to himself and that he was incredibly possessive; that was ultimately the greatest tragedy.”

The mermaids’ lagoon episode is sadly resonant as a foreshadowing of Michael’s own early death. In 1921, at the age of 20, while a student at Oxford, Michael drowned in Sandford Pool with his close friend and probably lover, Rupert Buxton, in an apparent suicide pact.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdShortly before the incident Michael had attempted to break away from Barrie – he had decided to leave Oxford and go to Paris to study art – but Barrie wouldn’t allow it. The verdict of the inquest was accidental death but many thought otherwise, including Michael’s younger brother Nicholas who is quoted as saying in an interview in the 1970s: “I’ve always had something of a hunch that Michael’s drowning was suicide – he was in a way the type i.e. exceptionally clever, with varying moods.” Dudgeon’s own views on the matter are clear. “I don’t think he wanted to commit suicide, but he was drawn into drowning by Buxton,” he says. “He dragged him to his death. And then of course it was all covered up.”

Barrie was devastated by the news of Michael’s death and never really recovered. “He physically crumbled – it almost destroyed him,” says Dudgeon. “I think that when it was all over and two of the five boys had died even Barrie felt the guilt.”

In 1928 Barrie finally published the script of Peter Pan, changing the ending. “At the end, Wendy’s mother puts bars on the windows of the nursery so that Peter Pan can never get back in – that certainly wasn’t in the original play,” says Dudgeon. “The close of the play originally took place in Kensington Gardens and Peter Pan and Wendy fly off together. I think the change of ending is significant.”

• The Real Peter Pan: The Tragic Life of Michael Llewelyn Davies, by Piers Dudgeon, published by The Robson Press, £20.