Interview with artist Norman Ackroyd

It’s fair to say that Norman Ackroyd’s father wasn’t thrilled to hear that his son wanted to be an artist but he took some comfort in knowing that he’d always have butchery to fall back on.

“My dad had a butcher’s shop and he insisted that me and my brothers learn the trade so we’d always be able to make a living,” says Ackroyd, now 80, who has never had to swap his paintbrush for a meat cleaver.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAfter leaving the family home in Hunslet, Leeds, to take up a place at the prestigious Royal College of Art in 1961, he not only earned a living, he built a reputation as one of Britain’s best printmakers.

“My mother encouraged me and it helped that I had a very good art teacher at Cockburn Grammar School.

“My father was generally too busy working to provide for us five children to think about it too much, but I think he was worried I wouldn’t be able to make any money at it,” he says.

A celebration of Norman Ackroyd’s talent is being held at the Yorkshire Sculpture Park in a solo exhibition of 68 works that runs until February next year.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

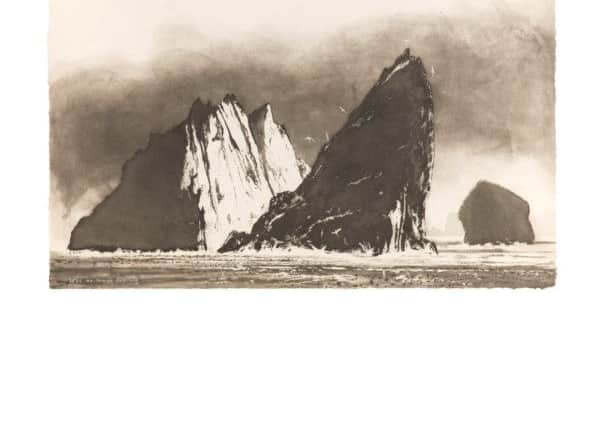

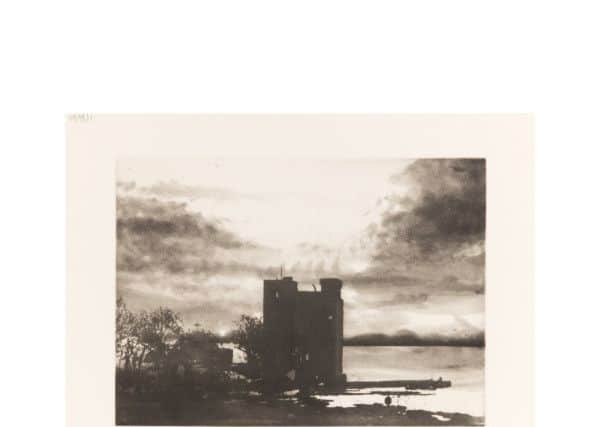

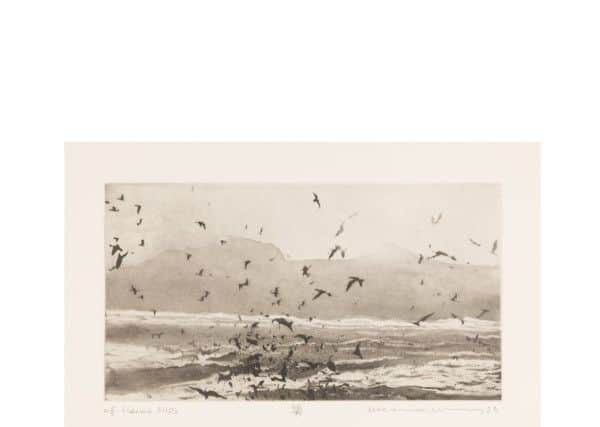

Hide AdThe Furthest Lands showcases a vast range of intricate aquatint prints and a small collection of watercolours. They capture the western edges of the British Isles while highlighting Ackroyd’s love of exploring and researching the history of the places he visits. The wilder and more remote, the better.

Starting in the extreme north of the Shetland Islands, the exhibition journeys south more than 950 miles to the far south-west point of Ireland, through a display of intricate aquatint etchings and a small collection of watercolours.

Ackroyd’s characteristic muted, mostly monochrome tones, are powerful and allow the viewer to feel the energy and essence of both familiar and faraway landscapes without the distraction of colours.

“It’s like a poem that can say something more than a 500-page novel,” he explains.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe exhibition features Skellig Sunset composed on the Skellig islands eight miles off the coast of Kerry in 2007 and his most recent, Off Hermaness, Shetland, completed this year.

“I was always fascinated by maps as a child and I loved geography and art at school. Somehow, I’ve combined all that,” says Ackroyd.

He has been intrepid to say the least but also respectful of the dangerous seas that surround the places where he finds most inspiration.

“There are some uninhabited islands where only the best local boatmen can land, so I find who they are and let them take me. They also provide me with snippets of oral history that you can’t find in books.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“I have been to some amazing places in the Orkneys where there are remains of ancient villages that are 5,000 years old.”

He is still sprightly for an octogenarian and he puts that down to walking a lot and playing golf, though age has imposed some limits.

“In some places the boat can’t get close enough to land so you have to jump onto a slippery rock and I’m not quite sure I’d manage that now, but I am still planning trips. Next year I am going to a couple of islands off County Mayo where the earliest Christian pilgrims landed,” says Ackroyd, who works plein air – outside in all weathers, making a watercolour in situ before creating an etching and ensuing prints in his home studio.

He made his first etching at Leeds College of Art 60 years ago.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“It had a wonderful etching workshop and was a very forward thinking art school. One of the tutors, Harry Thubron, knew all the contemporary artists and got them to visit, so we had talks from Victor Pasmore, Trevor Bell and Terry Frost. It was an exciting time.”

Storm Over Gildersome, completed in 1959, was made just before he moved to the RCA in London. The etching on steel depicts the skyline of the Leeds suburb. Never shown before, it will make its public debut in the YSP exhibition, along with a new limited-edition etching of the sculpture park’s landscape.

He visits the area often, coming up to visiting his sister in Leeds and his close friend John Bell of Thirsk-based gallery Zillah Bell.

He attributes his love of the region’s rural landscape to his brother, who was 12 years older than him and a keen fisherman. They used to catch the 4am milk train from Leeds up to Settle and while his brother cast his line onto the River Ribble, Ackroyd opened his sketchbook.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“I’d draw the surface of the water and a misty Ingleborough with no distractions. There were no iPhones and no radios back then. It was incredibly contemplative. I’d also pick mushrooms to make the best bacon and mushroom sandwiches I have ever tasted,” he says, adding that later, as a teenager, he often cycled into the Dales with his school pals. “I once got as far as Malham, which was a heck of a way from Hunslet.”

His emotional response to the landscape is there in his prints, which have been described as “brimming with atmosphere and a sense of place”.

Drawing, he says, underpins everything. “I see watercolour as a drawing medium and, of course, etching is all about drawing.”

He paints what is in front of him and he does it fast, often seated on a rocking boat looking towards the land.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe watercolour is then turned into an etching on copper plate. He also uses an aquatint box to creating tonal shading.

The etching and printing process is beautifully explained by Ackroyd in an interview by his friend and fellow explorer Robert McFarlane in a recent edition of Only Artists on Radio 4, which is available on catch-up.

In it, he also reveals a creative process many artists will find familiar: “Sometimes I can’t remember how I did it. I’m working in a trance. Some things don’t need an explanation,” he says.

The programme is recorded in his studio, which is attached to his home in Bermondsey. He has lived in London for most of his adult life.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“I have lived all over London but I really like this part. It reminds me of Hunslet as it was the industrial area where the dirty jobs got done,” he says.

He loves his live-work lifestyle and has no intention of retiring thanks to a compulsion to create and a workaholism instilled by his father and, he believes, by his working-class Yorkshire roots.

“There were 15 of us from Yorkshire at the Royal College of Art in the early Sixties, including David Hockney and Norman Stevens.

“We brought our Yorkshire accents and our work ethic with us.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“We were always first in at 8am. That was largely unheard of before we arrived but we all had that same commitment to hard work and that can’t be a coincidence can it?”

The Furthest Lands, an exhibition of work by Norman Ackroyd CBE, RA, starts today and ends on February 24, 2019, at Yorkshire Sculpture Park.

The artist will host a series of events at YSP, including an etching demonstration on February 16. The following day, Ackroyd will be in conversation with long-term friend John Bell from Zillah Bell Gallery, Thirsk.