An object lesson in mourning at this Leeds museum

Death. It comes to us all at some point or another. But while we inevitably shuffle off this mortal coil, it’s not a prospect we tend to dwell on or talk about.

For a long time it was a topic that was off limits, and in some respects still is, though there has been a move to encourage people to open up about this sombre subject – death can now be studied at universities – and funerals, rather than being morbid affairs, are often celebratory.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

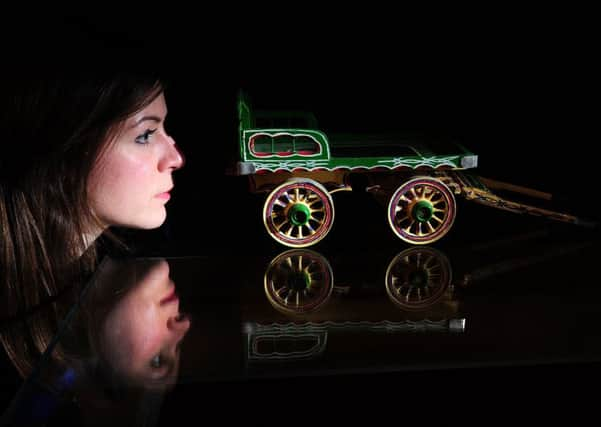

Hide AdIt’s the focus of the latest research project led by Dr Laura King, a social historian based at the University of Leeds. Living With Dying, funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Council, looks at how we mourn those close to us and Dr King, along with co-researcher Dr Jessica Hammett, has been working with Leeds Museums and Galleries on a new exhibition called Remembrance, co-curated by Abbey House Museum and the University of Leeds, that opened earlier this month.

The exhibition, which runs until the end of the year, features material from her research alongside that from the museum’s collection.

Dr King has been examining how people have mourned in the past and how society has changed. “It’s also about stories today and how people in Leeds grieve and remember their loved ones,” she says.

“One of the big questions is how people remember those close to them who have died and what they do day to day to help them remember.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThere are differences in the way we mourn today compared with our grandparents or great-grandparents. “There’s a trend now for using cremation ashes for tattoos, while other people make china cups and vinyl records using cremation ashes, and these kind of things weren’t happening earlier in the 20th century,” she says.

At the same time there is a common thread to our rituals that ties the two together. Objects, for instance, often take on particular significance.

“It might be a sea shell engraved in memory of someone who died, or it might be a simple object like a hat, or a child’s pair of clogs where a mother and child died and the father kept the boots as a memory of them.”

Places can also take on an added resonance when someone passes away. “It might be where someone’s ashes are scattered or the location of a gravestone, but it could also be somewhere special to a person that’s not formally marked.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“There’s also the things people do to remember which may involve keeping up a hobby like gardening which brings that person back to them, or playing particular pieces of music. And while these might shift over time there are similarities. People will always remember the people they love.”

There’s a perception that death is still a bit of a taboo subject but in many ways we’re more open than previous generations. “There are quite a lot of movements, like the Dying Matters campaign and the Death cafes, that are trying to encourage people to talk about it. So if you look for it there’s a lot going on at the moment,” says Dr King.

“At the start of the 20th century when infant mortality rates were so much higher it was difficult to ignore but there is quite a lot of evidence that it was still a bit of a taboo subject even back then and that people found it difficult to talk about, especially when children died.

“If you look at the personal testimonies and letters people wrote you find examples of people that didn’t know they had a brother or sister (who died before they were born) until after a parent died or they carried out some family history research. So there are ways death was hidden away.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdDuring the 1920s there was a surge of in interest in spiritualism and seances in the wake of the catastrophic loss of life during the First World War. People desperately looked for ways to somehow connect with sons or husbands who had been killed and were sometimes willing to suspend their disbelief in the process.

Mourning is often more complex than it might appear. “It’s not the case that it’s become more taboo over time,” says Dr King.

“A lot of people might be able to talk about death in an abstract way or about other people dying, but confronting your own mortality or what you want to happen at your own funeral, or that of a loved one, can still be very difficult.”

As part of her research Dr King spoke to various community groups in Leeds such as the Sikh Elders and as she points out there can be differences in the way different ethnic groups approach death and mourning.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“There are different practices towards mourning. Jewish people have their particular customs, while many Sikh people wear white rather than the traditional black that we’re used to and which was very important to the Victorians. We have a white outfit worn by a Sikh woman from Leeds called Satwant which she wore to her husband’s funeral.”

The nature of funerals have changed, too. “In the past if people couldn’t afford an outfit for a funeral they would wear an armband as a mark of respect and that still goes on today to some extent, though there’s a growing trend to wear brighter colours at funerals and make them less sombre events.”

It’s objects that we most associate with people, though, and Dr King came across the story of Amanda Reed, from Leeds, who kept an unusual memento of her father when he died, as she herself explains: “I held on to the last bottle of Old Spice I ever bought my dad, as from being a kid I always bought him this for Christmas, and every now and again I have a little smell of it because sometimes smells can remind you of people and it’s the Old Spice that reminds me of my dad.”

It highlights the different ways people remember. “For one person holding onto a plant might be really important, for others it might be visiting a place in the Yorkshire Dales or the seaside, but within that everyone’s basically doing the same thing, they’re finding their own way of remembering.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAnd she believes this is an important part of coming to terms with losing a loved one. “It’s something that happens to all of us and by understanding different traditions and the experiences of different groups of people we hope to encourage more conversations between younger and older generations.”

Dr King hopes the exhibition strikes a chord with people. “It’s a good way of getting people talking about death and dying without confronting it head on, it’s a positive way of thinking about it.

“It’s also a way of using history to explore how people want to be remembered in the future and by showing all the different ways this can happen it shows there’s no right or wrong way when it comes to remembering people.”

The Remembrance exhibition runs at the Abbey House Museum, Kirkstall, Leeds, until December 3.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIn 2009, the National Council for Palliative Care (NCPC) set up the Dying Matters Coalition to promote public awareness of dying, death and bereavement and to encourage people to make plans for the end of life.

Over the past seven years the separate Death Cafes have also been held across England, including here in Yorkshire.

The movement was started in 2011 by a former council worker Jon Underwood and his mother Sue Barksy Reid.

Inspired by the work of Bernard Crettaz, who established similar cafes in France and Switzerland, they wanted to create gatherings where people could drink tea, eat cake and talk about their mortality.