Starman who shot the ’60s

THEY were known collectively as The Terrible Trio. Terence Donovan, a hearty pillar of a man, liked to entertain his subjects. David Bailey’s modus operandi was to put those he photographed somehow on the back foot. And then there was Duffy.

Brian Duffy was the third of the laddish triumvirate and arguably the most edgy and experimental. His routine was to engage intellectually, get an argument going, calling black white if necessary.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdJoanna Lumley, who in her early days modelled for Duffy many times, remembers him as “...very frightening, but he was the business.” He often made his models sing while they worked.

The threesome took the world of magazines and advertising by the scruff of its neck. Until then photographers had been fey gents in three-piece suits, epitomised by Norman Parkinson, who referred to the three as the “black trinity”. They were mates but also rivals.

Later given the sobriquet The Man Who Shot The 60s, the boy who’d been rubbish at school was saved by an enlightened cultural programme aimed at young troublemakers. Duffy, who was brought up in north London by Irish parents, found his metier via St Martin’s art school, switching from fine art to fashion design.

He turned down a job with Balenciaga in Paris because his wife June was pregnant. Instead he took to fashion illustration for glossy magazines.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdOne day he saw some contact prints on an editor’s desk and decided to give photography a whirl, figuring it was a lot less labour intensive than drawing and had the added bonus of involving beautiful women.

When it came to fashion Duffy had the knack of creating the illusion that the models inhabited the clothes by taking them out into the streets and snapping them with a new-fangled 35mm camera.

This young gun in a black leather jacket saw himself as an artisan, yet in the 60s it was the photographers who were the stars, not the jobbing models who turned up to pose for them carrying their own holdalls of make-up and accessories.

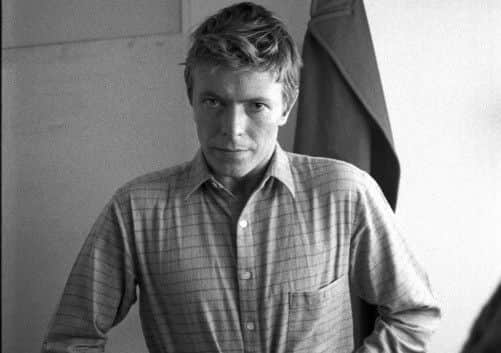

Brian Duffy’s restless, innovative and mercurial talent was used to photograph a roll call of those who were at the heart of the 60s cultural zeitgeist.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“He photographed Jean Shrimpton, Terence Stamp, Tom Courtenay, Peter O’Toole, Sammy Davis Jnr, Reggie Kray, Paul McCartney, John Lennon, Peter Sellers, Yves Montand, Michael Caine, Brigitte Bardot, Harold Wilson... so many,” says Duffy’s son Chris, who has curated the Duffy Archive since his father died of degenerative lung disease in 2010. A selection from the archive will arrive in Leeds next month.

Chris, 56, remembers the revolving door of celebrity at his father’s studio in the basement of the family home.

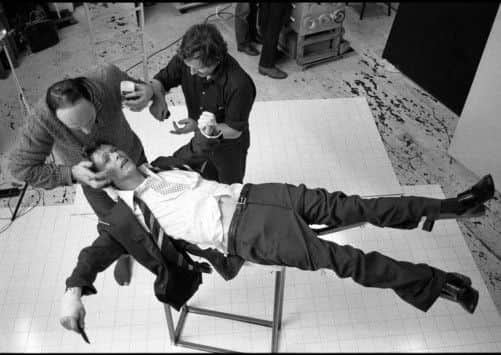

“Peter O’Toole and Terence Stamp were always popping round and we children just thought that was normal. They all knew each other, and Duffy (he always refers to his dad by the professional handle) was loved by clients and subjects because he was a risk taker, interested in setting himself technical challenges and working them out.”

For many years he was a staff photographer for Vogue, but later worked for Elle and Harper’s Bazaar, before tiring of fashion and moving on to advertising. One Sunday morning the teenage Chris came downstairs to hear his father playing a new record. It was Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders From Mars by David Bowie. Duffy had been taken on board to photograph the androgynous young star from Bromley, in what was to become a close professional and personal relationship spanning a decade and collaboration on five albums.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“Tony DeFries, Bowie’s manager, introduced Duffy to Bowie,” says Chris. “Tony really created Bowie in a sense, and got him signed to RCA then steamed them for a lot of money. When it came to shooting the images for Aladdin Sane, Tony said ‘I want this to be the most expensive LP cover ever’.

“His thinking was that if marketing Bowie was costing them a mint then they’d have to work very hard at promoting him to get their money back. And it worked beautifully – the team were put up at the Beverly Hills Hilton, the most expensive materials and dye transfer techniques were used and the prints were done in Switzerland.”

The album cover is up there with the handful of most memorable images in pop history. “Bowie was obsessed with Elvis,” says Chris Duffy. “He told Duffy that he was interested in the lightning bolt logo often used by Elvis, and although the make-up artist Pierre Laroche was there, he drew the shape he wanted for the lips himself.

“Over 10 years Duffy did five big sessions with Bowie, including The Thin White Duke, Lodger and Scary Monsters. Bowie is like a sponge, a magpie absorbing a range of ideas and working them into something else. But no artist works in isolation. The two stimulated each other’s creativity, and Bowie trusted Duffy to come up with the right concepts, whether for the elaborate set and rigging for The Lodger shoot or the plainer set for Scary Monsters, where the idea was more around the outfit.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThere was a time when the pop superstar would turn up in a limo for tea with the Duffy family, and young Chris would invite his Bowie-obsessed mate John to come and meet his idol. “But he’d hide in my bedroom, too overawed to come downstairs. I think it’s the biggest regret of his life.”

When Brian Duffy died, David Bowie sent a fond message of respect and condolence to the family.

Not long after their last collaboration, Duffy became utterly disillusioned with photography in general.

He felt the technical challenges of image making had been answered, and that he’d said all he had to say (although he’d also dabbled briefly in film, including co-producing O! What a Lovely War with Richard Attenborough and Len Deighton).

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdOne afternoon in 1979, he “just blew”, says Chris. Duffy took his archive of negatives and began to burn the lot in a metal bin at the back of his studio. Alerted by the fuming smoke of the slow burning film, someone called the council and a little man turned up to tell Duffy he had to quench the fire.

No-one is sure of how much was lost, but the remaining material – still a considerable amount – was kept in storage by the family. Meanwhile Duffy disappeared from public view for 30 years, concentrating on his other love, the restoration of antique furniture.

In 2005 he was diagnosed with pulmonary fibrosis, possibly linked to the chemicals used in his furniture work. In 2008 Chris Duffy, who had been working his way through his dad’s images from decades ago, persuaded him to have his first ever exhibition.

The show, staged in London in 2009, was a huge success, and no less than his father deserved, says Chris. Duffy’s images are currently also at the centre of David Bowie is, the biggest selling exhibition ever held at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London. Before he died, the BBC also screened the documentary The Man Who Shot The Sixties, in which Duffy took new portraits of subjects from way-back-then Joanna Lumley and David Puttnam.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdWhile tickets for the Bowie exhibition in London are now rarer than hen’s teeth, a gallery in Leeds has scored the coup of securing a 10-week show of 20 David Bowie images by Duffy, including previously unseen pictures of the star behind the scenes and the precious original (and only) Aladdin Sane print.

“It’s a thrill to get these two names, Duffy and Bowie, together in one show and especially to be able to show some images exclusively, “ says Sharon Price, co-creative director of White Cloth Gallery.

“His legacy has been a little bit swallowed up by those of Donovan and Bailey because they continued in photography long after he gave up.”

Chris Duffy, himself a very successful photographer who learned his craft as his father’s assistant, is pleased at the chance of taking Duffy’s work beyond London.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad““I have felt very strongly that artistically his legacy had been lost because he turned his back on the profession so long ago.

“I simply want to make sure he is reinstated in public perceptions as one of the most important photographers of the 60s.”

The Duffy Collection will be at White Cloth Gallery, 24-26 Aire Street, Leeds LS1 4HT, from May 2 to July 17. Information: 0113 218 1923 or www.whiteclothgallery.com