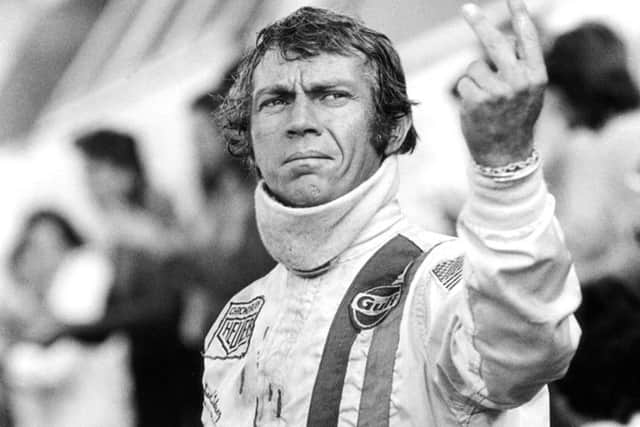

Steve McQueen and the need for speed

It was the oldest, most famous race in the world: the 24 hours of Le Mans. And Steve McQueen wanted to put it on the screen.

The idea was to film the entire Le Mans race and then recreate it over three months with the same drivers. McQueen wanted to deliver the ultimate racing movie, a film that presented the smells, the vibes, the excitement, the thrills, the sheer nerve-bending energy of Le Mans.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAnd to direct it he invited John Sturges, the filmmaker who had given him early breaks in Never So Few and The Magnificent Seven, and turned him into a star in The Great Escape.

“This is the story of racing, man. This is the guts!” recalls assistant director Les Sheldon. “You’ve got motor racing and you’ve got Steve McQueen. What have you got? You’ve got everything!”

In his career McQueen had been linked with a string of films that for a variety of reasons never got made. There was Roy Brightsword, a Western, The Yards at Essendorf, a war story, Man on a Nylon String, a thriller about mountaineering. And Yucatan, a tale of treasure-hunters and motorbikes in Mexico. But the movie that became McQueen’s obsession was Le Mans. And it was to break him professionally, personally, psychologically and financially.

The motoring Press asked the same question in unison: would the 40-year-old actor – the biggest movie star in the world at that time – race for real at Le Mans? At a Press conference a weary McQueen answered them.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“If I weren’t so rotten inside for money I would probably tell them to go screw [themselves]. But I need the money to make the film so I will not race in Le Mans.”

The cold fact was that the risks were too high. Drivers died all the time in the high-speed, high-risk world of motor sport. McQueen’s insurers were adamant he would not join that tragic tally.

To shoot the real race McQueen developed a camera car to capture genuine footage of competing drivers. It was a unique point of view from a driver’s perspective: from McQueen’s perspective, crammed in that tiny cockpit. He wanted the audience to have the authentic experience. At race speeds.

McQueen famously had no sense of danger. So in asking drivers to perform a ballet, a choreographed recreation, was pushing the boundaries to the extreme. British driver Derek Bell suffered facial burns when his car burst into flames during one sequence. Motor racing was a blood sport and to McQueen the blood that was spilt was a price worth paying to achieve his dream.But later when driver David Piper, filming a scene twice to cover the requirements of what the script might be, crashed and had to have part of his leg amputated, the film took on a grimmer mood. McQueen felt responsible.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdMcQueen was under immense pressure, much of it of his own making. Effectively co-directing the movie, as executive producer he was also the employer of Sturges, his old friend and mentor.

But when the film was revealed as a succession of lengthy race sequences with very little plot, Sturges left the project. At the same time McQueen’s increasingly open dalliances with other women put paid to his marriage to wife Neile. He was taking drugs. And after the Manson Family murdered his friend Sharon Tate at a party to which he had been invited, his paranoia skyrocketed and he began packing a pistol.

“There was really no script,” says one crew member. “We were winging it. In the meantime until we got somewhat of a script we were just shooting footage.”

By that point it was July 1970, McQueen was five weeks into production and one-and-a-half million dollars over budget.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdMcQueen had a mental picture of a documentary that offered viewers an immersive view from the steering wheel. Hollywood tradition demanded a dramatic story. Despite multiple writers being hired, there was none.

McQueen would later comment: “We tried to show in the film, rather than trying to explain it, why a man races, the feelings that he gets from it. It’s a great sense of freedom. It’s a high of one sort or another.” But that didn’t translate to a standard movie. The only option was to take over the picture. Thus McQueen was persuaded to give up his salary and sign over his producer’s involvement. The dream was over. But McQueen didn’t quit. He couldn’t. He had to finish Le Mans. So after a two-week hiatus he accepted unknown director Lee Katzin as Sturges’ replacement. The film wrapped in November 1970.

When it was released in 1971 McQueen didn’t bother to attend the premiere. “He was sort of melancholy, I think,” remembers Neile. “He said, ‘It’s done.’ I’ve never seen the movie. It’s so difficult for me. Steve lost his wife, lost his marriage, lost the film... Lost everything. The world just became a different colour to him after that film.”

Over the next few years McQueen did some of the best work of his career in films such as Junior Bonner, Papillon and The Towering Inferno. But he gave up racing, remarried and moved to a secluded beach house in Malibu. He died from cancer, aged just 50, in 1980.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdPart of McQueen’s racing legacy involves son Chad, now 54. Son followed father and in 2006 had a devastating accident that left him with injuries to his spine and neck. Says Chad: “I broke everything in my body. Would I change anything? No. There is nothing better. Motor sports is the strongest drug in the world.”

Like father, like son.

Steve McQueen: The Man and Le Mans is released today.