Bringing the house down

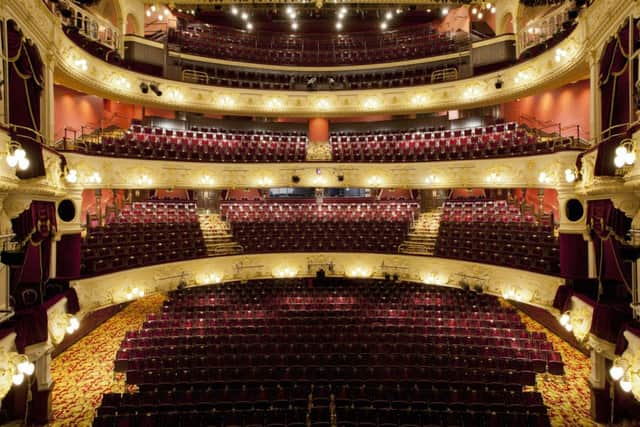

There are some pivotal moments when a disaster can turn into triumph. On Christmas Day in 1985, the Newcastle fire brigade was alerted that smoke had been seen billowing from the historic Tyne Theatre, which was being painstakingly restored. The Tyne was a Victorian building in the centre of the city, with ornate plasterwork and, more importantly, had one of the few remaining backstage areas with all the original equipment for lifting, raising, lowering and shifting scenery.

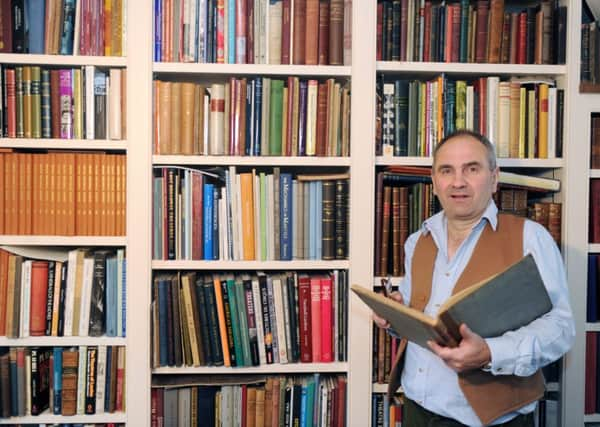

“I remember being contacted that day and being told of the fire,” recalls Dr David Wilmore. “For me, it was a tragedy, because I’d just spent three whole years working on the area, and I knew it intimately. Had all that effort, all our painstaking work, gone up in smoke?.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdMiraculously, someone had had the foresight to bring down the fire curtain after the Christmas Eve performance, and that, along with the timely arrival of the firefighters, had prevented the blaze from reaching out into the auditorium. The damage was still substantial, but nowhere nearly as bad as it might have been.

For David, who now lives in Dacre, near Harrogate, that blaze proved a decisive moment. While he had started off studying for a geology degree in Newcastle, a PhD in theatre research at Hull proved more to his liking.

“History for me was more fun when it was about the more immediate past, and not several million years ago. That fire was the final realisation that theatre and all things theatrical were my passion”.

David, who grew up in Beverley, is now one of the world’s leading theatre experts. If someone wants advice on how to restore a historic theatre or a performance space, wants information on its history, or just wants to know how it can fit in with today’s cultural scene, then it is more than likely to be him who gets the call.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIn Yorkshire alone he has been called in to give his advice on buildings as diverse as The Grand in Leeds, Harrogate’s Royal Hall, The Georgian Theatre in Richmond, The Theatre Royal in Wakefield and the “sleeping beauty” that is The Grand in Doncaster. There are many more on the list.

After we talk, he’s driving up to Settle to meet a team in the town who want advice on re-imagining their own little theatre. Tomorrow he could be in London, in talks with Andrew Lloyd Webber’s Really Useful Group – David advised on the removal and storage of the stage machinery at Her Majesty’s Theatre, home for many years to the long-running Phantom of The Opera. When that show closes (if it ever does), he will be called in to put it all back again.

Next week he could be in Middlesbrough, where he wants to see the old Empire returned to a theatre. Or Darlington, where a plan to save the beleaguered Civic seems to be making headway. “That’s all part of the fun,” he says.

“You never know when someone is going to call and ask for advice or support on some project or other. It could be anywhere.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHe is also a conservator, historian and collector on a grand scale. Those people who loved the now-vanished Scarborough Opera House, might like to know that it hasn’t disappeared completely. Under Wilmore’s careful supervision, the complete auditorium was dismantled, and is now laying safely in special crates in a Bristol warehouse.

“We couldn’t save the entire building, but we could rescue much of the inside,” he says.

“That means that if someone wants to build a new theatre, but one with a traditional interior, we have one ready and to hand. It is not unfeasible that it could be bought by some organisation somewhere else in the world. Dunfermline’s old theatre was taken down brick by brick, to be rebuilt in Sarasota, Florida. It can happen – and it does.”

Perhaps surprisingly for an expert in theatre conservation, David has much praise for the pub chain Wetherspoons.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“The company has done so much to keep distinguished buildings in so many towns open, rather than having a demolition ball knock them down. They may be pubs now, but who’s to say that a lot of the Wetherspoon property portfolio couldn’t be returned to original use? At least places like the Prince of Wales Theatre in Cardiff, the Opera House in Tunbridge Wells and the Winter Gardens in Harrogate are still standing.

“Let’s not forget that at the end of the First World War, there were more than 1,100 theatres across the UK. Today, there are not even 200. Over a thousand have been smashed into rubble, often wilfully and shamefully, and that is nothing short of a national disgrace.”

He believes that his obsession with the country’s theatres may have come from his grandparents, who were both professional singers, and then music teachers.

“I’d sit on my grandfather’s knee in front of the piano when I was about four or so, and the music must have soaked into me,” he says fondly. He is also an expert on the lives and works of Gilbert and Sullivan, and has just taken part in the International Festival dedicated to the writer and composer of the Savoy Operas, which was held in Harrogate. And he loves an ironic quote by Gilbert, who once said of a collection that he “saved it for the nation – which means that it will never ever be seen again!”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdDavid says: “He hit the problem right on the head – so many great collections of interest are donated by their owners to museums, galleries, whatever, and that’s it. They remain out of sight and only accessible – often after a lot of pleading and hard work – to people doing research. They should be more readily on view.”

As for his own collection, it now numbers more than 100,000 drawings, plans, photographs, programmes, catalogues and ephemera. It occupies much of the top floor of the home he shares with his wife Katherine and three children.

Stories rattle out of him. How he was involved in the TV production of JB Priestley’s novel Lost Empires, which starred a very elderly Sir Laurence Olivier and a very young Colin Firth.

“Sir Laurence got out of his car at the theatre where we were shooting, and had to be helped to his dressing room by two nurses.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“When he want required for his scenes, he tottered feebly to the side of the stage. He was very, very frail, and I thought ‘He’ll never last until lunch!’, and yet, when the director shouted ‘action’ it was as if he had been given a charge of electric vitamins. He stood up, marched forward, and was magnificent – and word perfect.”

There’s another about how he went through 10,000 architectural drawings to try to discover the original designs for the Leeds City Varieties. How two of his most treasured possessions are a pair of watercolours by the great theatre designer Frank Matcham, and how he discovered the whereabouts of several surviving backdrops of the legendary Howard and Wyndham pantomimes.

Then there’s the tale of his realisation why, when some theatres had been restored, the sight-lines for the audiences had been ruined – the reason was that the original seats had been ripped out, and new ones put in, and the replacements were of a different shape and size, altering the designer’s intentions completely.

He believes that theatres are sustainable if they are for and of the communities around them. They have to be supported by shops, pubs and bars. They have to radiate outwards, and be invitings. And he sings the praises of most of the Yorkshire councils which have championed old theatres. “I think that we are, by and large, in pretty good shape when it comes to conservation and restoration and thank heavens for the Heritage Lottery Fund and their incredible support, but at the back of my mind is the line that ‘It may be here today, but if it goes, it is gone forever’, and that is always a tragedy.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdDavid’s specialist company is Theatresearch, which can be a one-man-band (him) one week, or employing 20 to 30 specialists when a project is under way. And he is committed to training apprentices in vital creative theatre skills. In Yorkshire, he’d love to help get the Doncaster Grand up and running again, and one of his favourite venues of all is the Barnsley Theatre Royal.

“It now functions as a night club. But it still functions, and is cared for, and that always gives you hope. My belief, my work, is about conserving the past, but delivering something for the future use of all.”

If he could find just one supposedly lost theatrical artefact, what would that be? He says, without a second of hesitation, “The autographed copy of Gilbert and Sullivan’s manuscript score for their first operetta, Thespis. That’s from 1871. I believe that it was lost in a fire – but there is always hope that it may turn up somewhere.”

If it does, then it is almost certain that it will be Dr. David Wilmore who discovers it. And where will that priceless collection of his go when an inevitable time comes?

“The University of Hull is in the frame,” says David, “but that’s not set in stone. It’s a ‘maybe’. God willing, I’ll be given a good many more years to make up my mind.”