Poet’s own story feeds into new play

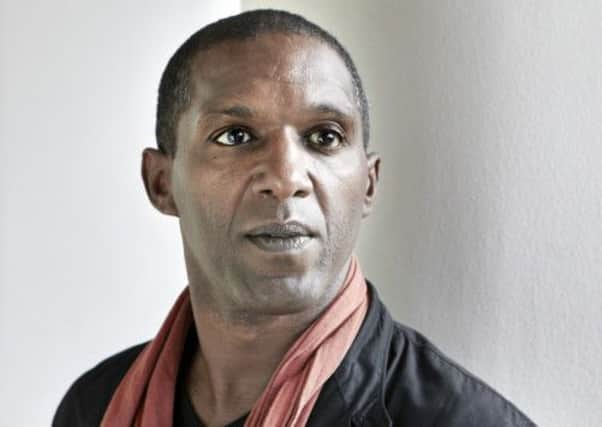

Lemn Sissay is wearing bright red-rimmed, dark-lensed sunglasses. It is not a sunny day in London.

The glasses couldn’t be more appropriate, even though the weather renders them ostensibly entirely counter-productive. The brightly coloured glasses with a darkness sum up perfectly the outlook of Sissay, one of our most celebrated poets, and a man with an unflinchingly positive view of the world – despite some of the real darkness he has seen.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHow are you? is a perfectly normal opening pre-question to our interview, once we arrive at an Ethiopian café Sissay insists we find, mainly because “Ethiopian coffee is the best in the world”.

The question prompts the answer: “Yeah I’m alright, today’s a good day.”

He repeats it, almost as though he is saying it to himself: “Today is a good day.

“I tend to live in a ‘today’s okay, tomorrow may be a disaster’ sort of state. That’s just how I look at it.”

Pessimistic?

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“No, no. When I say that, I mean now is good. Tomorrow could be brilliant, it could be terrible, but now is good. People ask me how I am I always say that now is good, it’s a reminder that today is good and in this moment, it’s important to recognise that.”

It’s little wonder that Sissay has to remind himself that ‘today is good’. Growing up he had a good many days where ‘today’ was not good. An Ethiopian by birth, Sissay was given to Manchester social services and was fostered by a very religious English family. Sissay has previously said that he didn’t realise when he was younger that his white parents were not his actual parents.

“My foster parents were essentially training me to be a missionary at the time. It was naive rather than evil. Everyone wants to give their child what they think is their greatest gift, they hadn’t had a child before and I think their belief was that their religious beliefs were the greatest gift they could give.

“They did horrific things, but I’m sure they thought they were doing the right thing. What’s that phrase about the road to hell being paved with good intentions,” says Sissay, with a staggering absence of anger. “I’ve been angry. I think anger is something to work through – it’s an expression of the search for love.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdSissay, born in 1967, was given to be fostered by his Ethiopian mother and was taken in by Manchester Social Services. He was fostered until he was 11, but then the parents who took him in and raised him as their own returned him to the care of Manchester Social Services when he was 11-years-old. He spent the next seven years living in the care of social services.

It was only when he was 18 that he was given his birth certificate and discovered he was Ethiopian and later, for a BBC documentary called Internal Flight, he travelled to Eritrea to find his mother and her family.

“It dawned on me that I’d been betrayed. I got to see that betrayal and experience it in its fullest. How was I? I was hurt. I was a hurt kid who didn’t understand what he’d done,” he says.

Despite the hardships he had experienced by the time he was a teenager, somehow Sissay had discovered writing and had his first collection of poetry published at 20. When he was 21 he and his work was the subject of a double-page spread in the Guardian, lauded as an entirely new voice. It seems an obvious question to wonder if writing was some kind of escape from this extreme life he found himself living.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“I’ve heard this idea of writing as an escape, as therapeutic or something, but I don’t recognise that, for me it has always been an exploration,” he says.

“I see poetry, and my use of it over the years, as an exploration of the landscapes of imagination – and I consider imagination as real as the pen and paper you’re writing with. It’s an actual landscape you can explore with writing and with poetry.”

Sissay’s latest project is an adaptation of Benjamin Zephaniah’s novel, Refugee Boy for the stage. The play made it’s debut this week at West Yorkshire Playhouse.

The story centres on 14-year-old Alem, brought to Britain from a war-torn African state as protection from the civil war raging back home. Sissay, who finds parallels in the story of the Refugee Boy with that of his own story, could not be more perfect to adapt the story.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“Everything in writing is autobiographical. The way I describe this coffee is different to the way you describe this coffee,” he says.

“With an adaptation it is slightly different. I talked to Liz Lochhead (National poet of Scotland) about this and she said that for an adaptation you have to disrespect the original text. Benjamin has done his job, it’s mine to turn the work into something for the stage.

“It’s an incredibly exciting process – at once restrictive, because it’s a story that you owe something to, but liberating because you are exploring what is relevant to you from a particular story that already exists.”

It’s not just the passion Sissay has for the project that makes him the perfect person to be working on it – nor his existing relationship with Zephaniah. The reason Sissay is perfect to tell the story of the Refugee Boy is because of the unique personal experience he brings to the situation he is writing about.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“The idea of migration is something that people do from the moment we are born,” he says. “We migrate from our mother’s womb, from childhood to adolescence. There has never been a time in history when people haven’t migrated.

“It is anti-human to deny or not accept migration. Our anti-immigration notions are based on nothing more than fear. The wind doesn’t need a visa application.”

Behind the glasses, Sissay looks on the world in a powerfully unique way.

A poet and playwright

Lemn Sissay is a poet and playwright. He’s an associate artist at London’s Southbank Centre.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHe is an honorary Doctor of Letters, awarded by Huddersfield University. He is also the town’s Literature Festival Patron.

He curated the world’s first Literature Festival of The Sea. His poems appear on buildings in Manchester and London, including The Royal Festival Hall. His Landmark Poem Gilt of Cain, commissioned by the City of London is based near Fenchurch St station and was unveiled by Bishop Desmond Tutu in 2006.

He is author of five books of poetry spanning 25 years. Refugee Boy, West Yorkshire Playhouse, to March 30. 0113 2137700.