The remarkable rise of Grimethorpe choreographer Gary Clarke

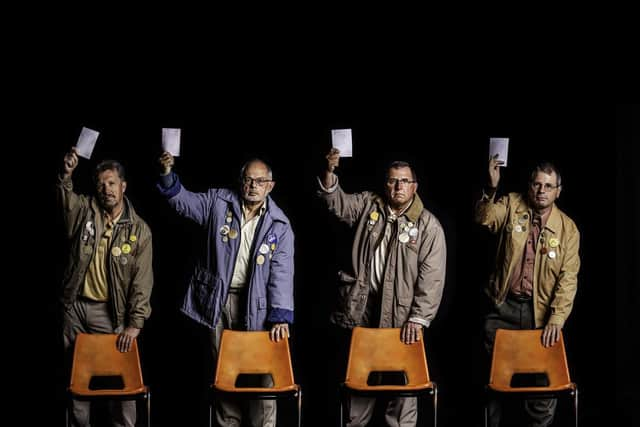

The acclaimed dancer and choreographer was mid-way through touring his latest work Wasteland, which had been receiving five star reviews, when the UK lockdown was announced.

“We were on the way up to Scotland when we got a phone call from the theatre saying ‘turn around’,” he says. “Then one by one we lost all the rest of the shows on the tour.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIt was a huge blow but Clarke quickly bounced back, securing funding to pay his dancers and launching GCC Digital in early May, a five-week programme of online classes, workshops, talks and activity.

Currently he is working on a new piece for the Lawrence Batley Theatre (LBT) in Huddersfield. The theatre has commissioned him and two other choreographers – Jordan James Bridge of Studio Wayne McGregor and Daniel de Andrade, associate artist at Northern Ballet – to create three site-specific works for camera exploring the theme of isolation caused by the international lockdown due to the coronavirus pandemic.

All three of the works in Locked down. Locked in. But living are being filmed in the empty theatre building, and will be made available online next month. Clarke has a long relationship with the LBT, having performed there many times over the past 20 years. It is also where, at the age of 16, Clarke saw his first live performance of contemporary dance.

“That’s what inspired me to want to become a dancer,” he says. “I feel there has been a real connection between my work and the theatre and its audiences, so I was thrilled when I got the phone call. The fact that it was a new commission responding to what has been happening felt like a really exciting opportunity in these pretty dark times.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdClarke’s piece, But living, will be a solo work performed by dancer Gavin Coward, a long-time collaborator and an old friend. “We met when we were training, so I have known him since we were 18; he is an amazing performer. Also, we are lucky enough to be working with Grimethorpe Colliery Band. By chance I had a phone call from one of the managers just after I got the commission. They said they were looking to do something a bit more experimental – I think the exact word used was ‘bonkers’ – and asked if I had anything in the pipeline.”

The band immediately got on board. Then having visited some of the spaces at the LBT that he might use as locations – such as the boiler room and stairwells – Clarke began formulating ideas for the project.

“I wanted to do something that was about escapism, that was fun somehow and had a narrative that audiences could be excited by.” He was inspired by watching the very first film version of Alice in Wonderland, a 10-minute silent short made in 1903, and felt that its themes of isolation, altered emotional states and escape chimed with the current situation while, in terms of storytelling, also allowed for a sense of playfulness.

Hugely respected as a multi-award-winning choreographer and regarded as one of the UK’s leading independent contemporary dance artists, Clarke was born and raised in the South Yorkshire mining village of Grimethorpe in the 1980s.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHe experienced first-hand the suffering and hardship endured by mining communities during the 1984-85 Miners’ Strike and lived through its devastating consequences. “Grimethorpe was known as one of the most deprived villages in Europe,” he says. “Growing up in that environment, art was something you just didn’t do, there was no provision for it, no money for it and as a young man I would have been expected to work in the mines or a factory.”

Clarke found his own way, through dance which he came to as a way of coping with what was happening around him. “For me dance was a kind of escapism. In the 1990s there was a lot of deprivation, crime, violence, domestic violence and drug-taking – it was pretty bleak. The whole village just imploded.

"A lot of my friends would go out and fight whereas I just used to lock myself in my bedroom and get out all my anger and frustration through movement. It was at the time when techno music came out and I was really into that – I used to go to raves and clubbing.

"My thirst for movement came out on the dance floor; it was a very visceral exploration of movement. Then I ended up going to Northern School of Contemporary Dance – that’s where I learnt discipline which I found very odd at first. For me dance was something instinctive and primal so to be told that I was going to have to wear tights and stand at a ballet barre was a bizarre experience.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdOne of the key points in his early career was being cast in Matthew Bourne’s brilliantly subversive, ground-breaking Swan Lake – in which the swans were all played by male dancers.

It burst on to the stage and instantly became a huge global hit. “It was a beautiful moment because, for obvious reasons, I was always getting the Billy Elliot comparison and at the end of the film Billy grows up and you see him getting the part of a swan in Swan Lake. It was my second job – I was 23 I had not really been anywhere and suddenly I was travelling the world meeting all these amazing people; it was just phenomenal. I feel very lucky and proud to have been part of that iconic work.”

He may have travelled the world, performed on some of the most prestigious international stages and worked alongside A-list movie stars like Tom Cruise, Brad Pitt and Eddie Redmayne in his role as a movement director on Hollywood films, but home is still in Grimethorpe.

That’s where he returned to after living in London for several years and then Belgium. “I ran away from home when I was 18, life was tough at the time and I got out, but I ended up coming back and I’ve not left. I get on really well with my family, all my friends still live here and I feel connected with the community in Grimethorpe. When I was away, I missed that community spirit I grew up with; being back here is a joy.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHe says that lockdown has allowed him to reflect on the future a little and given him the time to consider how he might expand and develop his company going forward. “We have been having conversations about our mission,” he says.

“As an artist I am making a commitment to create work that comments on and reflects working class history and culture. It is about representing real communities on professional stages, based on fact not fiction, using my platform of contemporary dance. It’s an unusual medium to do it in, but I see it as my duty as a working-class artist to communicate and help promote those stories.”

Locked down. Locked in. But living.

Available to watch online September 28-October 12. Tickets are £12.

To book visit www.thelbt.org

Support The Yorkshire Post and become a subscriber today.

Your subscription will help us to continue to bring quality news to the people of Yorkshire. In return, you'll see fewer ads on site, get free access to our app and receive exclusive members-only offers.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdSo, please - if you can - pay for our work. Just £5 per month is the starting point. If you think that which we are trying to achieve is worth more, you can pay us what you think we are worth. By doing so, you will be investing in something that is becoming increasingly rare. Independent journalism that cares less about right and left and more about right and wrong. Journalism you can trust.

Thank you

James Mitchinson