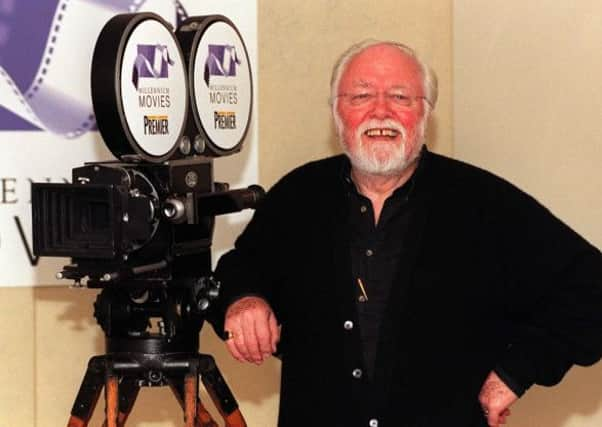

Trademark twinkle of Dickie Attenborough

IT WAS a mistake to be taken in too readily by Richard Attenborough’s cuddly exterior.

For if darling Dickie (or Lord Attenborough to give him his formal title) greeted everyone with a smile and a handshake, inside the velvet glove were knuckles of steel.

By his own admission Attenborough was a slogger.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHe struggled for almost 20 years to make a film about Gandhi but even when the studios sought to sabotage the project – “Dickie, who on earth wants to see a film about a little brown man dressed in a bed sheet carrying a bean pole?” one executive asked – he ploughed on, seeking finance and backing wherever he could get it.

He was in Yorkshire in 2001 for the sixth Bradford Film Festival. Strolling through the National Museum of Photography, Film & Television he was mobbed by fans who recognised him from Brighton Rock, The Great Escape and Jurassic Park.

And he greeted each and every one like a long-lost friend. That was Attenborough’s magic, his gift and his appeal. That innate sense of community and accessibility.

I had seen it previously at a preview of Shadowlands at the old Leeds Odeon in 1993. Then Attenborough strode into the auditorium with a microphone to greet the audience and introduce the film. He waved and smiled, winking and making the most of that trademark twinkle.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdOn the way out he pointed at me and gave me a thumbs up. The girl I was with nudged me violently in the ribs, as if I hadn’t noticed. He didn’t know me but, for a moment, I was the most important person in the theatre. It takes class to make a person feel like that. My girlfriend talked about it all night.

Attenborough enjoyed an extraordinary evolution. He began as an actor pigeonholed as “an idiot little spiv or a quivering psychopath. I was stuck with both those for quite a long time and being stuck with those really decided me, later on, to give up acting.”

But before he quit performing to concentrate on the Gandhi project he produced some stinging films rooted in social commentary. The Angry Silence, a damning indictment of union intransigence and their stranglehold on British industry, was one. Oh! What a Lovely War, an excoriating musical on the futility of conflict, was another.

Delivering movies with a message became Attenborough’s forte. He played Halifax-born serial killer John Christie in 10 Rillington Place, an authentic portrait of a monster that the actor described as “this poor, demented man”.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAnd in A Bridge Too Far he directed a stellar cast in the last great anti-war movie of the 1970s.

“I don’t make innovative movies,” Attenborough once told me. “I make craft movies – they have beginnings, middles and ends.

“I’m not interested in the pornography of violence. In fact I’m distressed by it.

“I’m not interested in special effects. I’m interested in people, human beings and relationships.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“I have tried to make films about the dilemmas and the problems and sacrifices that human beings are involved in. I’m not an auteur.

“I’m not a great filmmaker. I’m a craftsman. And I can’t contemplate the idea of retirement.”

Lord Attenborough, who moved to a care home in 2008, died at lunchtime on Sunday aged 90, his son Michael said.

BAFTA described its former president as a “titan of British cinema” who set an example of “industry, skill and compassion”.