From Whitby to Australia: Recreating the voyage of Captain Cook

The idea had been to sail the vessel from Whitby to the other side of the world. It would have been a recreation of the explorer’s 1768 voyage and arriving in 1988, the year of Australia’s bicentennial, there would be cause for a double celebration. “Cook’s Endeavour had been built in the Fishburn yard in Whitby in 1764, but by the time I picked up the book again the plans to build a replica had faltered,” says John. “Over a pint I declared if the council couldn’t bring the project to fruition then I would. I knew there was no way I would be able to afford to build a replica, but I reckoned I could build a modern steel yacht and sail the same route Cook had done all those years ago.”

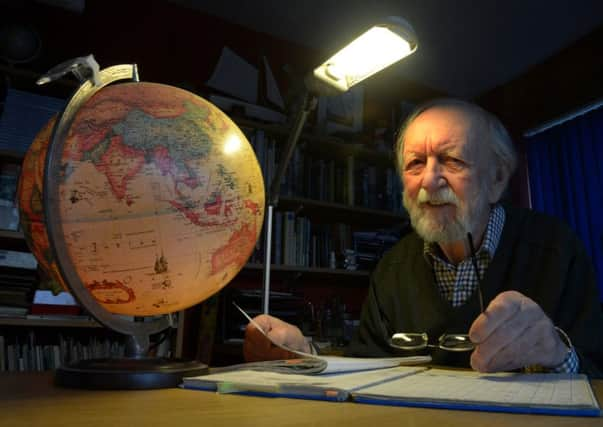

It was the middle of 1986 and the Cook’s Wake project was born. John, from Kirkbymoorside, near Helmsley, wasn’t a particularly wealthy man and had no lucrative backers. What he did have in spades was enthusiasm and a healthy disregard for those pessimists who said his plan was impossible.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“I’ve always had an affinity with water and I’ve always been pretty practical,” he says. “When I was 12 years old I built my first canoe out of orange boxes and I guess I have always thought about what’s possible rather than impossible.”

John also wasn’t a complete novice. A qualified yachtsman instructor, a few years earlier he and his family had spent more than a year sailing to the Red Sea and back in a boat they had appropriately named Ambition. That journey, while memorable, had also had its fair share of hair-raising moments and one particularly bad storm in the Mediterranean meant John’s wife, Brenda, was unwilling to set sail again.

“Had I known just how difficult it would be, who knows whether I would have ploughed ahead? But I was a man on a mission. I just knew it was something I had to do.”

With the words of Captain Cook, who had once said: “I who had ambition not only to go farther than anyone had been before, but as far as it was possible for one man to go”, ringing in his ears, John began the long and arduous process of turning his dreams into a reality.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe couple sold their bed and breakfast business to fund the building of the yacht and John began scouting for prospective crew members, who would pay up to £3,500 for a place on the boat.

“The scale of the project quickly became apparent. Our first boat which had taken us to the Red Sea and back had almost succumbed to storm conditions in the Eastern Med, so this next boat required a brand new design. I was confident that I knew what needed to be done, but until you see it launched into the water there is always a little nagging voice in the back of your head.”

The steel hull arrived at John’s home in Kirkbymoorside a year before the sailing date and having been placed on the lawn next to the family home it became something of a local landmark. The Pauls’ garage was turned into a temporary shipwrights workshop and when John wasn’t teaching art classes at a nearby primary school, he spent all his spare time fitting out the boat.

“On the day of the launch, the boat was driven across the North York Moors to Whitby harbour,” says John, who has only just got round to chronicling his attempt to follow in the explorer’s wake in a new book. “Making our way past Cook’s home territories was quite poignant and when Ambition II was finally lifted into the water we knew there was no going back. I was going to be away from home for two years. It made no economic sense and there were certainly enormous physical dangers, but I suppose that was all part of the adventure.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdCook’s Endeavour had a crew of 94 and was able to carry enough food and water for up to 18 months. John’s boat was significantly smaller. While there was space for up to eight crew, six was ideal and there would only be enough provisions on board for eight weeks.

“There were a lot of what ifs,” says John. “I didn’t know how she would fare in a storm, I didn’t know whether the sails would be adequate or whether all the various instruments would work.”

Back in the 18th century, communication between a ship’s crew and home was by letter which could take months, sometimes years to arrive. In 1987, technology had moved on, but John’s ability to call home was still limited.

“Today we are so used to being able to pick up a phone and call home from wherever we are, but when you’re in the middle of an ocean it really is just you and the waves. Of course much had changed since Cook’s day, but we notched up the same average speed and sailed beneath the same stars.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdWith John having secured his first crew mates, Ambition II sailed out of Whitby on a journey that would take them to the Canary Islands, Brazil and the Falklands and onwards towards New Zealand and finally Australia.

En route the boat faced storms with gale- force winds, John was forced to ask one of the crew to leave for repeatedly ignoring orders and seasickness also took its toll.

“The first days at sea after a stopover are often the worst. There is no solution except to hope it goes away and while it lasts jobs below deck are onerous in the extreme. The heat below, the smell of food, diesel and unwashed crewmen can act on seasickness like a time bomb.

“When you are on board a boat there are certain things you can plan for, but each day there are problems which have to be solved. One of the crew members was profoundly deaf. He could lip read, so I didn’t think it would be a problem, but when night fell that was it, we were scuppered. We worked round it, we had to and those are the moments you realise just how important team spirit is.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe sheer physical effort of keeping the boat moving took its toll and chances to sit back and relax were few and far between. However, as well as the surging waves and the heavy downpours, there were also some once-in-a-lifetime moments.

“There was one day I’ll never forget in the South Atlantic. I looked out ahead and saw eight whales, their backs arching above the water. Clouds of warm breath steamed from the blowholes. These were very big creatures and we were, by comparison, quite small. Suddenly one leapt vertically from the water. It was a breathtaking sight and I think we all felt incredibly privileged to have seen them so close.”

On August 2, 1988 John and the rest of the Ambition II crew finally sighted Australia. Like Cook they wanted to begin their visit from Botany Bay and were greeted by various civic dignitaries and reporters keen to interview the English adventurers. “It was an incredible time. We spent the next nine months visiting schools and sharing our experiences, but there was still the return journey to do and money was fast running out.”

To insure the boat for the full route would have cost £6,000. It was money John didn’t have, so he took the risk of paying for just the most dangerous sections. “Fortunately the gamble paid off. It could have gone dreadfully wrong, but we arrived back on British shores in December 1989.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdA few years later, John sold the boat which he had sailed around the world for £50,000. He went back to teaching and later set up an architectural design business. Every so often he was called upon to skipper a boat and occasionally secured spells of work as a sailing instructor.

“We now have six grandchildren and I would like to think that if they can learn anything from my adventures it is that there is nothing wrong in attempting something that at the outset seems almost impossible, beyond reach.”

• John Paul will launch his book Sailing in the Wake of Captain Cook’s Ship Endeavour at the Moorside Room in Kirkbymoorside on April 9&10 where there will also be an exhibition of his artwork.