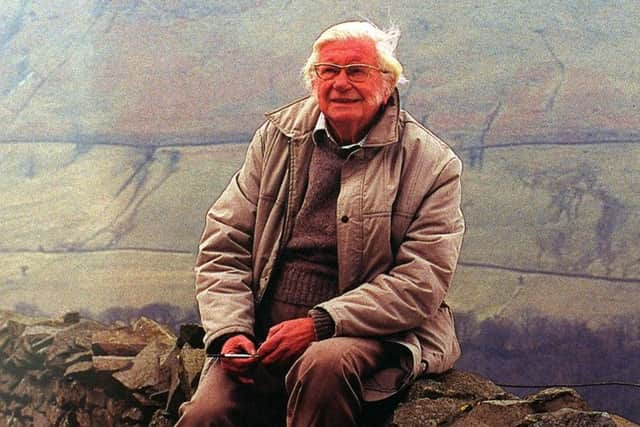

Words with Wainwright: Off the beaten track with the guidebook guru

The mood eventually lightened, he says, but when they went for a walk in nearby countryside Wainwright once again showed his irascible side. “When a particularly vociferous trio of ramblers strode past,” Brabbs says, “he started chuntering to nobody in particular about the peace and tranquillity of the countryside and the unnecessary blazoning of more than one path through walkers not maintaining single file.”

Back at the hotel, unpunctual or not, Brabbs was trusted with the job of photographing Wainwright’s walks in the Lake District and along the Pennine Way, and three decades later he now recalls that first encounter with the author in a book compiled by over 200 people who knew or met him.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdBrabbs believes Wainwright’s surliness was the defence mechanism of someone who was actually shy and modest, and adds: “[He] was a perfectly amiable companion to those admitted through the protective barriers of gruffness and apparent indifference towards strangers.”

For someone known to be a recluse, though, he seems to have met an awful lot of people and there are numerous stories bearing out Brabbs’s assessment. Another photographer, Mike Bralowski, arranged to meet him to take a photo that would end up on the front of an Ordnance Survey map but, he says, the assignment got off to a bad start when, on hearing his voice – Bralowski lived in Devon – he immediately sensed Wainwright’s antipathy towards southerners.

Things got worse when a woman who was walking her dog recognised the author and asked for an autograph, only for her request to be “rudely rejected.”

Others who encountered Wainwright paint a picture more in line with Brabbs’s assessment of amiableness. Roger Scruton, who photographed him for a Sunday newspaper, remembers someone who was “easy to get on with, patient, and came across as a kindly gentleman”.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdJohn Burland, a scout leader in Otley, wrote asking if some of his drawings could be used in a newsletter. Wainwright replied not only granting permission but enclosed “a substantial cheque” to help subsidise the scouts’ weekend camps in the Lake District. Several great anecdotes illustrate Wainwright’s character. One is from January 1967 when he turned 60 and gave up the job of Kendal Borough Treasurer. His 16 staff decided to throw him a retirement party, bringing in sandwiches for a buffet and ordering a large cake with a figure of a mountaineer on the top.

Roger Bingham, a local councillors, recalls: “He refused to come out of his office and take part in the usual courtesies on his last day at work. Eventually, they took a slice of the cake to him, and he ate it in his office, worked on until 5pm and then left.”

Another Wainwright story comes from Andrew Nichol, who printed early editions of the famous seven-volume Pictorial Guides to the Lakeland Fells. In 1985, he says, it was calculated that the one millionth guidebook was due to be printed, and to mark the occasion the publishers decided to hide a specially marked copy among all the books going out for distribution. In its pages would be an invitation to have lunch with the great man.

It was sent out to a shop in Manchester with only Nichol and Wainwright knowing its location. Weeks passed and no one had claimed the prize, and finally Wainwright phoned to say he had gone off the idea and wanted the book back. Nichol drove him to Manchester where the author went in and bought the book. Why did he have second thoughts? “It was because he could not face the idea of eating with strangers,” says Nichol.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe transformation of Wainwright from recluse to TV star was remarkable. He did, however, make strict demands on anyone who wanted to make use of his fame. Take the sculptor Clive Barnard, who in the book performs the remarkable feat of putting the names of Alfred Wainwright and Jimi Hendrix next to each other (they were both turned into busts by him).

When Wainwright was brought to the Lake District studio by Andrew Nichol, Barnard was warned not to worry if the author walked out on him. “I’ll get him back,” Nichol told him. It just means I’ll have to drive him to Harry Ramsden’s in Yorkshire for some fish and chips, and stop at a pub where he likes the beer,” a trip Nichol described as “the placation run”.

In the event, a drive across the Pennines wasn’t necessary, but the TV and radio presenter Sue Lawley didn’t have it so easy when she tried to get him on Desert Island Discs.

“He would consent to appear only on certain conditions,” she writes. “To begin with he wasn’t coming to London. He’d been there once since the war, hadn’t liked it and didn’t intend to return. So we agreed to record the programme in the BBC’s Manchester studios – but here, too, there was a condition. If Wainwright were to travel that far south (remember that if you live in the Lake District, Manchester is in the Midlands) his journey would have to include a detour to Harry Ramsden’s near Leeds.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad• Encounters With Wainwright, compiled and edited by David Johnson. Published by The Wainwright Society, price £15.

ALFRED WAINWRIGHT GAVE HIS FIRST-EVER NEWSPAPER INTERVIEW TO THE YORKSHIRE POST. ROGER RATCLIFFE RECALLS WINNING AN AUDIENCE WITH THE FAMOUSLY RECLUSIVE GUIDEBOOK AUTHOR.

He didn’t want to be interviewed, and didn’t want to be bothered again, thank you very much, but after three months of trying my persistence paid off and I managed to extract a promise to meet me. He laid down one condition, though. The Yorkshire Post must publicise a donkey sanctuary at Ramsbottom.

It was a small price to pay, and an article about the Bleakholt animal charity in North Lancashire duly appeared. So a week later, in November 1976, the venue this Howard Hughes of the Lake District chose for the interview was a back room at Kendal Museum.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAnd there he sat for the best part of an hour, tamping Three Nuns tobacco in his pipe, releasing clouds of pungent smoke and listening to the scattershot of questions that I was asking with increasing desperation to try and elicit more than his curt replies of “Yes” and “No”.

My exclusive interview was turning into a disaster. Here was the great Wainwright, a best-selling author whom few people knew much about and even fewer had ever seen, and he was giving nothing away.

His reticence verged on Trappism, and to try and get a conversation going I began to recount my own experiences on the Lake District fells he had described, sketched and mapped with such genius. Suddenly, names like Mickledore and Jack’s Rake seemed to have the effect of magic incantations, and he began to talk. When finally he paused to relight his pipe I dared to suggest a bar lunch and without answering he picked up his cap and coat.

Next door at the County Hotel we ordered food and half pints of bitter, and I tried to continue the interview. But now I had to compete for his attention with young women who were coming into the bar.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“She’s got a beautiful face, don’t you think?” he asked me more than once.

“Yes she has.” I always had to agree with him, because his eye for beauty was not confined to landscapes. But I was then aged 23, and it felt strange sitting in a bar eyeing up the talent with a 69-year-old man.

When the girls finished their lunches and left I managed to concentrate his mind on my questions. He did most of his walking in Scotland, he said, because the Lake District fells were now too busy. “I don’t like crowds. The people who are coming here aren’t the right type. You get coach parties, groups of children trailing round the villages looking for the next ice-cream shop.”

Which was my cue to land a question I was holding back to the end. Had his guidebooks made the Lakes too busy? Did he accidentally ruin the solitude he cherished?

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHe tapped a matchstick on his pipe stem for age and I wondered if I’d gone too far.

“People say so,” he said finally. “The erosion of some paths is causing a lot of problems. They are being kicked away. I didn’t think what might happen.”

I gave him a lift home, knowing he’d enjoyed watching the girls in the bar at the County more than he had the interview. It would be another decade before Wainwright agreed to become public property by submitting to the razzmatazz of TV cameras, Press agents from a big London publisher, and Desert Island Discs. And only then to sell books that would raise money for donkeys and other unwanted animals.