Fear that tipped the Western world into a recession

But for some at that IMF gathering in Washington DC five years ago, it was the first time in their professional lives that they simply had no idea what to do.

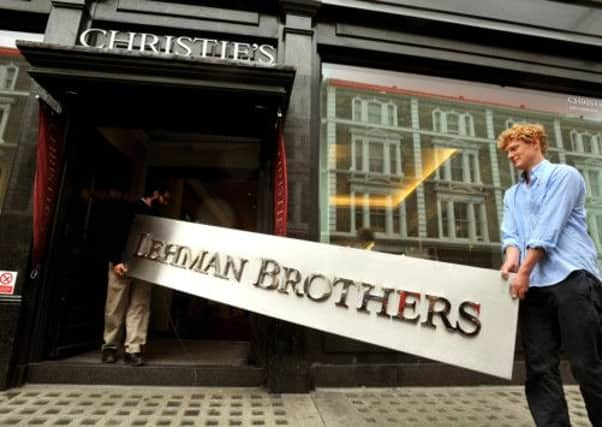

Lehman Brothers had collapsed, sending shockwaves through the international financial system, and no-one knew what would happen next.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdJohn Hooper, who was representing National Australia Bank’s global institutional business, remembers the atmosphere as “a bit tense”.

“It was an unprecedented situation,” said Hooper, who is now chief operating officer at Yorkshire and Clydesdale banks.

Discussions centred on whether to recapitalise banks. The Australians and Canadians didn’t see the need; by and large their institutions had not dangerously over-stretched themselves.

The Americans introduced the Toxic Asset Relief Programme, a US Treasury fund designed to shore up its lenders.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdBut it was Britain, under former Prime Minister Gordon Brown, that led the way in the Western world with its rescue package for banks.

Hooper recalls the “slightly unreal threat that if measures put in place failed then the banking system would fail”.

“That was very hard to contemplate, without sounding like Jeremiah or Henny Penny,” he added, referencing the prophet and folk tale about a chicken who believes the world is coming to an end.

But fear alone was enough to tip the Western world into a deep recession.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdJohn Stewart, the former chief executive of NAB, illustrated the effect of that fear with this analogy: a disease is spreading, it is transmitted by human contact and it is impossible to tell who is carrying it. “Now I want you all to shake hands,” he told a room full of bankers.

The global financial system, a vast, inter-linked network of parties and counterparties, had become contaminated, a challenge for NAB, which was in the habit of raising money offshore and swapping it into Australian dollars.

At the time, it used four big investment banks to provide this service. One was Lehmans.

Hooper had to renegotiate swap deals with other banks and try to understand the risks involved with each counterparty during a time of unfolding crisis.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“The key was making timely decisions with very limited information in an environment where everyone was nervous about each other.”

For NAB the challenge was systemic, rather than specific, unlike institutions like Halifax Bank of Scotland and Bradford & Bingley for whom the seizure of the wholesale funding markets had near fatal consequences.

FIVE years ago, Tom Riordan was the chief executive of Yorkshire Forward, a Labour government-funded regional development agency.

He recalls a regional strategy review the organisation held in 2007, the year before the crisis, which flagged up “a worrying downside risk” to the economy.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“But no-one predicted what happened, although people knew there were concerns,” he said.

The immediate threat for the RDA was the “massive potential impact” that the financial crisis could have on businesses in Yorkshire.

The Lloyds rescue of HBOS was announced just days after the collapse of Lehmans, sparking fears of enormous job losses in this region.

The following week brought the news that the Government was nationalising Bradford & Bingley in an another hammer blow for Yorkshire’s financial services industry.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdFortunately, one of the board members at Yorkshire Forward, the well-connected industrialist Lord Haskins, knew the chairman of Lloyds, Victor Blank, and managed to arrange an emergency meeting.

“That day on the train down we had a feeling of the importance and gravity of that meeting. There were so many people employed in Halifax. It would be devastating to the town if the Halifax was to close.

“Those were the thoughts we were having, given what had happened to Lehman Brothers.”

The meeting took place at the top of the ten-storey Lloyds HQ in Gresham Street in the City.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdBlank was awaiting them, so was Helen Weir, then the head of retail and a key decision-maker at the bank.

Riordan and Haskins pressed the case that the Halifax brand was the major asset that Lloyds would be inheriting and they could not decimate the town, or Yorkshire more generally, or they would lose that brand.

“They got what we were saying,” said Riordan. “They didn’t give any guarantees over jobs because they couldn’t but they did agree to work closely with us and they did recognise what we were saying about the quality of the workforce.”

Rosie Winterton, the former Labour minister for Yorkshire, helped open doors and made sure that decision makers in London knew the importance of Yorkshire, said Riordan.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdShe arranged a meeting between Yorkshire Forward and Alistair Darling, then the Chancellor, about Bradford & Bingley, the ailing mortgage lender.

“We were trying to stabilise the company and make sure again that we did not have a major collapse of a significant institution,” said Riordan.

In the event, the collapse of HBOS and Bradford & Bingley led to the loss of thousands of jobs in financial services sector, but Yorkshire operations still remain at the heart of the Halifax brand and UK Asset Resolution, the Crossflatts-based ‘bad bank’ managing the loans of B&B and Northern Rock.

IN September 2008, financial markets went through seismic adjustments which were felt by institutions of all shapes and sizes throughout the world.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIn a market town in North Yorkshire, David Cutter watched the events unfold on the news.

Cutter, soon to become chief executive of Skipton Building Society Group, recalls a sense of excitement and apprehension at his impending promotion at a time of such turmoil.

“Some markets were impacted overnight,” he said. Faced with the closure of the wholesale market and ratings downgrade, Skipton, along with many other institutions, joined the scramble for retail funding.

It made acquisitions and sold assets to raise funds and stay profitable during the crisis, which had a “profound effect” on the group, said Cutter.

Asked about the biggest lesson learned during the crisis, he said: “Cash is king.”