Kim Cotton: Why I am still proud to have been Britain's first surrogate mum

When Kim Cotton became Britain’s first surrogate mum, she gave birth to a baby girl weighing 7lb 13oz amid a wave of criticism from MPs, a deluge of negative headlines and the threat of prosecution.

It was January 1985. Band Aid was still number one with Do They Know It’s Christmas?, but charity was in short supply when it came to reports of how the 28 year old was to be paid £6,500 for the child by a Swedish couple she had never met. The deal had been brokered by an American surrogacy agency and Kim was portrayed as a woman who had put her womb out for rent.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“It might have been only 30 years ago, but it was a very different world,” says Kim, now 60. “People didn’t understand it, so they automatically thought it was wrong. I’m just glad that Facebook or Twitter didn’t exist back then. It was one thing being vilified in the press, but it would have been quite another to have been hung out to dry on social media. Someone had to be the first and we were pioneers, but at the time it was very difficult.”

As the controversy mounted, Margaret Thatcher’s government felt compelled to order an enquiry. Headed by the ethics expert Dame Mary Warnock, her subsequent report effectively made commercial surrogacy illegal.

“I think it shows just how far we’ve come that Dame Mary has since admitted that she did surrogacy a great disservice,” says Kim, who had two children of her own and is now a grandmother of five. “She was swayed by public opinion and the laws passed in 1985 were a knee jerk reaction to newspaper headlines like ‘Born to Sold’.”

While there are no exact figures, it is estimated that one surrogate child is born in the UK each week, but the controversy has never quite gone away. Just this week the High Court heard the case of one surrogate mother who had refused to hand over the child despite an agreement with the girl’s genetic father and his wife. While she had failed at an earlier hearing to regain care of the little girl, judges have now ruled that she can see the youngster twice a year.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdFollowing the birth of her first surrogate child, Kim admitted that her own experience hadn’t exactly been a happy one and it was the reason she decided to set up the support group Childlessness Overcome Through Surrogacy (COTS).

“After I gave birth I had to leave the child in hospital as she had been made a ward of court. I have never attempted to make contact because I’m aware she may not know that she was born through surrogacy. Every time it’s her birthday I do feel a little wistful, but if she has been told the details of her birth then I would be fairly easy to track down. It has to be her decision.”

When Kim became a cause célèbre there were fears that surrogacy would turn babies into commodities to be bought and sold. Now the procedure is legal as long as mothers are not paid more than ‘fair’ expenses, which tends to be about £15,000. However, if problems further down the line are to be avoided, it’s not just money which needs to be discussed.

“The important thing is that the couple and the surrogate are like-minded and are absolutely open with each other about all possible outcomes,” she says. “In the early days of COTS we would arrange initial face to face meetings, but now it is often done by Skype.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“There are things people prefer not to think about, like what happens if the child is stillborn, but it’s important that all parties know what the next step will be so that nothing comes as a surprise. At the end of those discussions we advise that a written agreement is drawn up so everyone knows where they stand.”

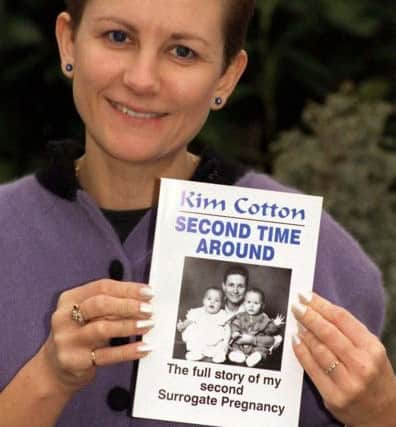

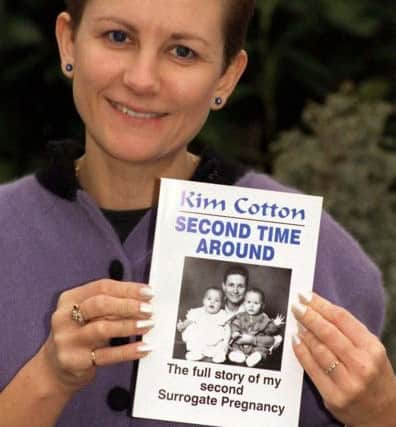

In 1991 Kim went through a second surrogate pregnancy giving birth to twin girls on behalf of an infertile friend. It was she says a far better experience and she is still part of their lives.

“To them I feel like an aunty or a close family friend. I am absolutely not their mother, but it’s been lovely to see them grow up. Everyone is different, but many of the couples who have been supported by COTS have remained friends with their surrogate. It absolutely can work.”

Recently COTS celebrated its 1,000th birth. Amy Croft, who was born without a womb, and her husband were introduce to mother of two Gemma Sanderson after they were referred to the organisation by a fertility clinic. By the time baby Theo arrived earlier this year, the two women had become extremely close with Amy attending all the developmental scans.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“That was really lovely to see, but we know there are many other couples out there who we haven’t been able to help,” says Kim. “We are regularly forced to close our books because there is such a dire shortage of surrogate mothers. Changes in the law to allow same sex couples to marry and adopt children mean we have been inundated with gay men wanting a child.

“Our experience has shown these couples make wonderful parents and many surrogates particularly choose to work with our gay couples. That’s great, but it means our waiting list has doubled but the number of our volunteer surrogates hasn’t.”

While the idea of a gay couple having a surrogate child would have been unthinkable in the 1980s, there are some things which haven’t changed.

“When a surrogate baby is born many hospitals won’t allow the handover of the baby to its new parents in the actual ward,” says Kim. “Often it has to happen in the carpark and that makes everyone involved feel they are taking part in something clandestine and sordid, instead of something wonderful.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“There are also issues around the application for legal guardianship. The paperwork can take six months to process and until then even if the baby was conceived through IVF host surrogacy and is genetically unrelated to the birth mother in the eyes of the law she is still regarded as the mother. Worse still if the surrogate is married her husband is classed as the birth father and both their names are put on the first birth certificate.

“Most surrogates aren’t happy with this situation and we would really like to see all court officials involved in the process working off the same page. At the moment there are no set guidelines and mistakes can not only cause more expense, but also unnecessary emotionally upset.”

Kim, who lives in Milton Keynes with her husband Geoff, would also like to see infertility talked about in schools, alongside sex education and contraception, but despite the misconceptions which still surround surrogacy she says she has no regrets about the life changing decision she made three decades ago.

“Surrogacy is empowering,” she says. “It’s a wonderful thing to be able to bring a life into this world. And that’s something you should never have any regrets about.”