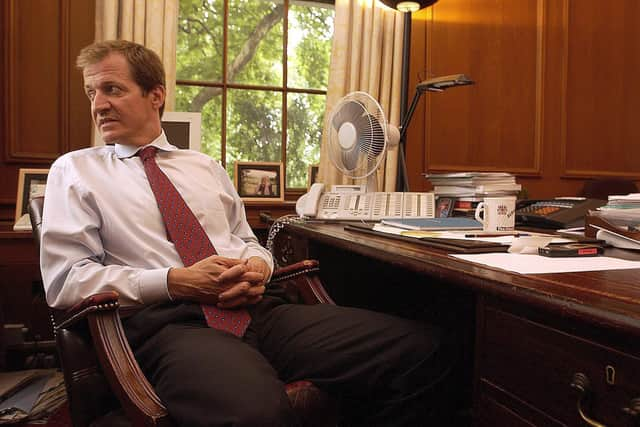

Why Alastair Campbell is opening up about his family’s history of mental health struggles

Followers of Alastair Campbell’s career will already know he has mental health issues. In 1986, while working as a political journalist, the Keighley-born Campbell suffered a psychotic episode in the middle of the Scottish Labour Party Conference. After a night of heavy drinking he found himself standing in the foyer “enveloped in a kaleidoscope of sound” – some of it real, some not.

Though treatment helped him kick his alcohol abuse, deeper problems remained. During his years in government they bubbled beneath the surface before returning with a vengeance when he (nominally) left politics.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdA nadir came during a walk on Hampstead Heath, when a particularly punitive depression left Campbell hitting himself in the face. It was also a turning point: “Even as I was punching myself,” he remembers, “I was saying to myself, ‘You are f***ed unless you get some help’.”

Since then his mental health campaigning has pushed his problems into the public eye, but his family history with mental illness is less well-known.

Older brother Graeme lived a self-destructive life, and lost both his legs – “one for the booze and one for the fags” – before dying prematurely. Oldest brother Donald “loved people and loved life,” but suffered from severe schizophrenia.

Both siblings were 62 when they died – Campbell’s age when he started writing Living Better, his new book on living with depression. He’s now 63. The book is an attempt to rationalise and utilise this journey, and it starts starkly: “On a dark Sunday night last winter, I almost killed myself.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdYou might think the ensuing pages would have been tough to write, but Campbell found the experience cathartic, even agreeable. “I’ve never shied away from talking about this stuff,” he says, “and I like writing about mental health. The only difficult bit was writing about family members – apart from that, I enjoyed it.”

He’s made several programmes and spoken at any number of events, but writing a semi-memoir gave him the space to delve into the detail.

Campbell is not an ordinary person, but he’s at pains to point out his problems are.

“There’s not a single family in the world that doesn’t have someone who’s struggled with mental health,” he says, “and part of the purpose of the book is to lay that wide open.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHis current mental state is “generally good”, but depression is a beast he’s learned to live with rather than conquer. “I accept the depression is part of who I am,” he says, “and that requires me to put in place things to help me stave it off. I do that pretty well – most of the time.”

When it does come, it’s “a dark grey cloud… that fills me with dread”, Campbell says, though he admits it’s difficult to describe it accurately. When he wrote the book he was “in pretty good shape”, and when you’re not in the dark place, it can be hard to rationalise what it was like.

In print and in person Campbell is characteristically solutions-based, and he spends the book’s latter half marshalling a dizzying array of tools and coping mechanisms, spanning conventional medications to electric shock therapy and genetics.

He’s tried all sorts: mindfulness, gratitude lists, a best-worst log, dream diaries.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIndeed, just about the only thing he hasn’t tried is the so-called ‘croft plan’ – a pet project of his psychiatrist’s that would see him live in an attic for a month with zero contact with the outside world.

He laughs when it’s brought up: “I saw [my psychiatrist] two days ago, and he said, ‘So, are we ready for the croft yet?’ He really swears by it, but no, I’m not.”

Most useful was the so-called ‘jam jar’ – an imagined container that holds all the different aspects of his life, and helps him work through them.

His most frequent ally is his ‘depression scale’, a one to 10 rating he gives himself every morning, to assess his prospects for the day ahead. Two is full of the joys of spring. Seven is “the signal to cancel meetings, stay indoors, avoid people”. Eight means stay in bed.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdCampbell has hit nine on several occasions, but 10 is “out of bounds”.

Now a seasoned mental health campaigner, strangers sometimes stop Campbell in the street to ask his advice. “I’m not a doctor, I’m a spin doctor,” he tells them, but he does pass on practical suggestions and, if possible, puts them in touch with suitable professionals.

For those that last saw him stalking the corridors of Downing Street and savaging opponents on Newsnight, this more intimate portrait of Campbell may seem difficult to reconcile.

“Anybody with a big public profile gets cut down to a cartoon,” says Campbell, “and my caricature was the shouty, ranty, Malcolm Tucker, control freak. There’s an element of truth there, but people are always more complicated.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe intense pressure of his job seemed a buffer against, and catalyst for, his problems. “I can never tell why a depressive episode comes on,” he says, “but I can see why people might see top level politics as a laboratory for psychiatric struggle.”

Campbell has long argued against public cynicism about government, but he’s currently finding it hard to practise what he’s preached. He found lockdown comparatively tolerable (“I had two bad spells, and one manic,”), but hated watching the news.

“My daughter found me watching TV one afternoon when I was a bit low. She said, ‘Dad, what are you doing, that’s self harm’. I said, ‘I’m watching Matt Hancock’s briefing’. She said, ‘Exactly’.”

He’d certainly make some changes if his hands were on the levers of policy – reforming the Mental Health Act, for starters, and investing heavily in child mental health services – but he’d like to see shifts across society.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHe’s adamant about the power of language, and the differences between how we discuss mental and physical conditions. “I remember talking to one of [my brother] Donald’s doctors,” he says, “and he said one of the hardest things when someone is diagnosed with schizophrenia is stripping all the things the family think it means.”

‘Committing suicide’ is another bugbear, as, he points out, the phrase dates from when suicide was a crime. “You don’t say, ‘He committed influenza,’ or, ‘He committed a broken leg’.”

There has been some progress – “people talk about it more, and there is less stigma” – but Campbell is clear there is “a long, long way to go”.

Campbell is not ready to rest on his laurels, but when he looks back over his life, he feels fortune over pride or regret. “I’ve been incredibly lucky with my family,” he says, “and being able to operate at a level where you can really make change – whether Northern Ireland, Kosovo, or winning elections. But I really, really want to make a difference in the mental health space.”

Friend’s loss hit home

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAside from his own struggles, Campbell has experienced a staggering weight of bereavement, from the loss of his parents and brothers, to friends and co-workers.

Prominent among them was Philip Gould, a long-time Labour strategist and one of Campbell’s dearest friends. “I never really understood the phrase ‘a good death’ until Philip,” says Campbell, who grew up in Yorkshire and attended Bradford Grammar School. “He really was extraordinary. He used every day to try and make things better for his wife and kids. I hope I get to that. At the moment I’m not in that zone at all.”

Living Better: How I Learned To Survive Depression by Alastair Campbell, is published by John Murray, priced £16.99. Available now.

Support The Yorkshire Post and become a subscriber today.

Your subscription will help us to continue to bring quality news to the people of Yorkshire. In return, you’ll see fewer ads on site, get free access to our app and receive exclusive members-only offers.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdSo, please - if you can - pay for our work. Just £5 per month is the starting point. If you think that which we are trying to achieve is worth more, you can pay us what you think we are worth. By doing so, you will be investing in something that is becoming increasingly rare. Independent journalism that cares less about right and left and more about right and wrong. Journalism you can trust.

Thank you

James Mitchinson

Comment Guidelines

National World encourages reader discussion on our stories. User feedback, insights and back-and-forth exchanges add a rich layer of context to reporting. Please review our Community Guidelines before commenting.