Foootball, Kes and Barry Hines: There's more to South Yorkshire's Hoyland than you think

They love their footie in Hoyland. Over the years the community – which is within the boundaries of bigger brother Barnsley – has had as many as six soccer teams. In no particular order, there’s been Hoyland Town FC, Hoyland Silkstone, Hoyland St Peter’s, The Rockingham Athletic Club, Hoyland Common Athletic and Hoyland Common Wesleyans – the last of which makes you wonder if they ever competed with the Hoyland Rather More Superior Wesleyans.

The moment of glory for Common Athletic FC was to attain the accolade of giving the Best FA Cup performance in the Third Qualifying Round. Those giddy heights were achieved in the 1949/50 season.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe question you’re all asking, though, where all of these teams played? For this neck of the woods has deep valleys and steep hills, with precious few level spaces. So where were the pitches? At many points, the views are quite spectacular, over lush woodland, and across the workings of what was the fourth Earl Fitzwilliam’s pioneering industrial complex at Elsecar – today it is the extremely popular Heritage Centre, with many attractions, which include its very own steam railway. It gives you an idea of the scale of vision that the Fitzwilliam family had – bringing together mines, a canal and later the railway, a unique Newcomen steam pumping engine, and everything that an industrial complex would require, on one site.

The aforementioned football teams must have had many ‘friendly’ rivalries. But that competitiveness was nothing compared to that between the two patrician landowners of the area. These were the Rockingham family, and the Fitzwilliams. Lord Rockingham was higher up the social pecking order, because he was a Marquess. One rung down the title ladder was the Earl Fitzwilliam. They were fiercely adversarial and tried to outdo each other in who could build the biggest number of follies. Between them, their families built and then extended the biggest private house in all of Europe, Wentworth Woodhouse.

The first Marquess of Rockingham died in 1750, and is buried in York Minster. According to one contemporary, his Lordship (who was Lord Lieutenant of the West Riding of Yorkshire) “drowned in claret”. His “five a day” were obviously bottles of good red wine. But he had been a keen sportsman, and ordered the building of Hoyland’s Lowe Stand, an 18th century folly, which is now in the hands of the Lowe Stand Trust. It looks rather like a picturesque tower but was first intended as a hunting lodge for the Marquess. And like most of the follies associated with the noble families, they had to be seen from their homes.

It’s a great shame that several of Hoyland’s smaller Georgian chapels, shops and cottages were swept away in the 1960s and 70s, but there are some gems remaining, and one is Hoyland Hall, once owned by William Vizard, an industrialist who owned a local pit, Hoyland Silkstone, a social reformer and a lawyer. He is one of those men who genuinely should have been recognised by a seat in the House of Lords, but he never achieved that, for he defended Queen Caroline against her husband George IV’s petition for divorce. The King demanded “Pain and penalties”. Vizard won the 1820 case, however he lost his chance of ennoblement. George IV never ever forgot anyone who opposed him, and he never forgave Vizard.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThere are still many notable buildings in Hoyland, and one has to be possibly the ugliest and most unprepossessing theatres in all of the UK. It is, however, culturally significant. It opened in 1893, however no-one knows who designed it. It may be that no professional architect wanted to admit to building what is, in effect, a square pink-red brick box. In its heyday, The Princess had over 1,000 seats, a full fly-tower so that scenery could be dropped in and out, and a large stage. By the time of the Great War it was converted into a cinema.

When it stopped showing movies in 1963 it became a bingo club, a snooker hall, and then a dance studio. Since 2014, a convenience store has used part of the space – but the dusty old theatre dressing rooms to the rear are still there. The Theatres Trust has The Princess listed as one of its buildings of interest. Its “little sister” can be found just along the road toward Elsecar. The Electra Palace was built in a cross-over style that is almost late Art Nouveau, and early Art Deco. She first welcomed locals in 1912, the year when the Titanic sank, and Barnsley won the FA Cup.

There were 600 seats when she opened, reduced to 440 when she was re-Christened The Palace in 1938. When she finally closed her doors in 1985, she was known as The Futurist, and is now a private home.

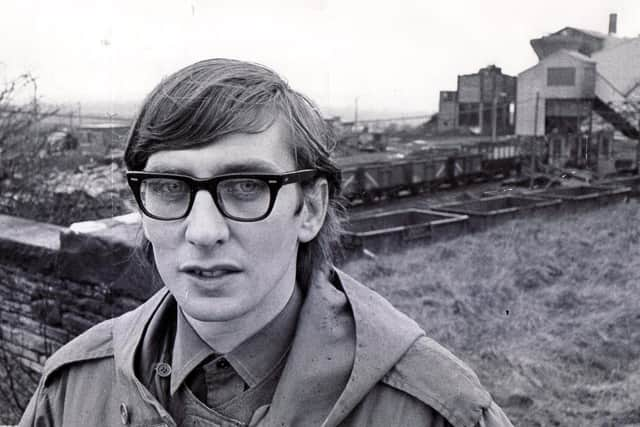

Both venues would have been known to author Barry Hines, and the comic and TV star Harry Worth, both of whom were born in Hoyland. A prolific writer, Hines (who was briefly employed as a miner, and who then became a teacher before writing full-time) is best remembered for A Kestrel for a Knave, which was later adapted for the screen as Kes, the remarkable film which was directed by Ken Loach.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdUnlike so many other film projects, Kes remained firmly rooted in Hoyland and Barnsley, for much of it was shot on location in the area, and which used local talent. The actors spoke in the authentic dialect of the community. When it was considered for the American market, executives at United Artists had a screening in Hollywood and later said they had a better chance of understanding it in Hungarian than the “incomprehensible” lilt of the Barnsley accent.

Hines, however, triumphed in the end, for his book has never been out of print, and is a mainstay of the English syllabus in many schools. The award-winning movie is in the top ten of the British Film Industry’s list of great British films. There’s also a blue plaque to commemorate Barry Hines in Hoyland Common.

Harry Worth was also the son of a miner, the youngest of 11 children – his dad died when he was only five months old, in a pit accident. He too went down the mines, and later confessed that he “hated every minute of it”. His salvation oddly enough was the Second World War, for he joined the RAF and became a member of one of a concert party, entertaining the troops.

He was originally a ventriloquist’s act, with a “bumbling” and apologetic presentation that was to become his trademark, and, while he was touring with Laurel and Hardy in the early Fifties it was the great Oliver Hardy who took Harry to one side and advised him to “drop the dummy, and concentrate on being a comedian”.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHarry took comic dithering to new heights, but he never ad-libbed, and stuck to his scripts. The result was a TV career that lasted until the late Eighties. Many people today can still quote his much-impersonated opening line (it never varied): “My name’s Harry Worth – I don’t know why, but there it is!”

Support The Yorkshire Post and become a subscriber today. Your subscription will help us to continue to bring quality news to the people of Yorkshire. In return, you'll see fewer ads on site, get free access to our app and receive exclusive members-only offers. Click here to subscribe.