The heartwarming story of how Yorkshire folk hosted German prisoners of war for Christmas

The story was not quite the same, however, for the thousands of prisoners of war - largely German - who would remain behind the wire of Britain’s numerous prisoner of war camps for years after the war’s end.

To much criticism from the public and other MPs, Clement Attlee’s post-war government ignored the Geneva Convention and slowed repatriation efforts for German prisoners - leaving some in Britain until as late as 1948.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

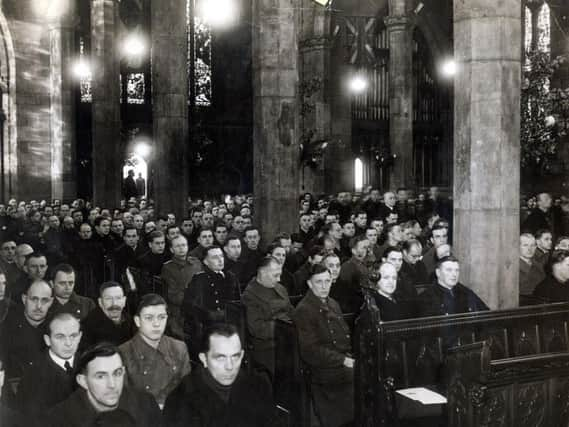

Hide AdThough many records detailing the locations of prisoner of war camps have been lost, by most estimations it was Yorkshire that was home to the highest number of prisoner of war camps in England.

While there was certainly some lingering hostility towards the prisoners of war, many local people in Yorkshire and beyond grew to feel empathy towards the prisoners’ plight of being stuck in a foreign land - especially over Christmas.

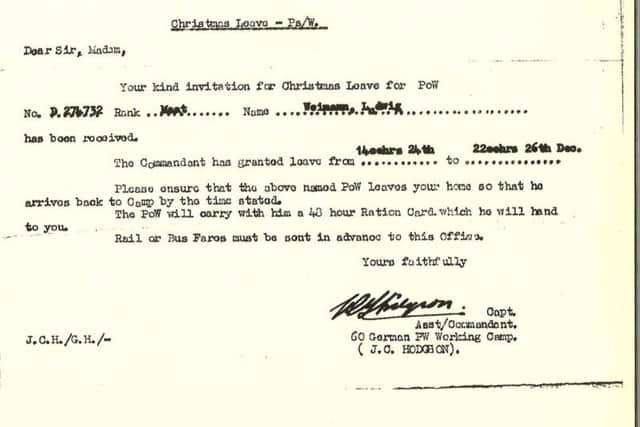

A ban on fraternisation between locals and prisoners of war was lifted late in 1946 just in time for the festive period, and what followed was a mass, heartwarming show of goodwill fit for a Hallmark film.

Local people decided to open their homes to prisoners of war over Christmas, sharing their food and hospitality with the men in spite of strict rationing still in place and the dust barely settled on the chaos of the war.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThough many British families did not speak German and many German prisoners of war did not speak English, it is reported that locals and prisoners muddled along with bits of sign language and pointing.

Even more extraordinary, in the case of one Sheffield family, a German prisoner was invited to a Christmas dinner before the war’s end - while one member of the family remained abroad fighting the German army.

It’s a memory passed down the generations to Bet Brooke, whose grandmother and grandfather, Mr and Mrs Goodyear, were head of the household on Bramley Avenue, Sheffield.

The family had come into contact with the prisoner, Josef Grudel, through Bet’s father (Mrs Goodyear’s son-in-law), who was working as an engineer maintaining vehicles in Finningley when his superior came to him one day with a man to help him with his work.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“When Dad came out from under the lorry, Joe was stood there in his prisoner of war uniform. They started talking and quickly became firm friends.”

As a result, says Bet, Mrs Goodyear invited Josef over for Christmas dinner - in spite of her own son still fighting in the navy on anti-submarine boats.

“My Dad had to find Joe a coat to cover his uniform as he was not allowed out in it, and he spent the whole day at my Nan’s.”

The family went on to befriend another prisoner of war, and Bet says the family remained friends with the two for the rest of their lives.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“As kids we went over to Germany to spend our holidays with the two families. I think I went about nine times in total.”

It’s a touching story of kindness, and far from unusual in Yorkshire. In January 1948, German prisoners of war stationed at Redmires camp near Knaresborough threw a belated Christmas party for 100 local children as thanks for the warm hospitality they’d received in the area.

The children were gifted with hand-crafted toys made by the prisoners, from little cars to carved animals. One prisoner of war even took on the role of Father Christmas, while a group of musicians played music for the community to sing and dance to.

While the government was failing prisoners of war, it was the goodwill of local people that lifted the spirits of so many prisoners of war stuck in Britain after the war.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThousands even chose to stay on instead of returning to Germany - so much so that the government had to adjust their target for the scheme offering settlement for the POWs.

It was the Christmasses in particular, however, that stuck in many POW’s minds for years to come. Like the brief Christmas truce of World War One, it was a moment when ordinary folk in Yorkshire and beyond put aside prejudice to bring joy to those who were once “the enemy”.

As one ex-POW put it, the act of human kindness shown by these people represented an entire nation, and his Christmas at a strange English home was one he wouldn’t forget “to my dying days”.

Read more on Yorkshire's prisoner of war camps and their locations: