The line that great granddad built

This weekend, descendants of the Victorian pioneers who made it possible will gather in the Dales to revisit it.

It will be an understated event – in stark contrast to the one in the US earlier this year, which marked 150 years since the pinning of the ceremonial gold spike at the spot where the train line coming west from the Atlantic Ocean joined the one going east from the Pacific.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

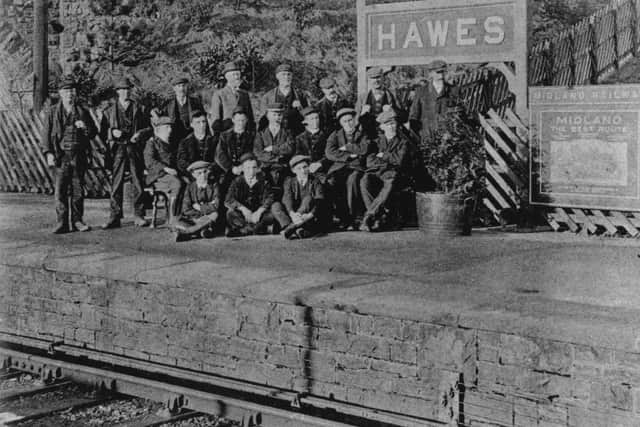

Hide AdIn the Yorkshire version, a small crowd will gather for a guided walk along an abandoned, seven-mile branch line and a series of talks at the Dales Countryside Museum – a collection of neat, stone buildings where Hawes Station once stood.

The spur to there from Garsdale was the last of five contracts on the mighty Settle to Carlisle route to be completed by the engineering firm run by Sir Abraham Woodiwiss.

For Susan Tripp, a retired London teacher and Sir Abraham’s great granddaughter, the event will a first chance to meet distant relatives, united by a shared industrial history. They will share pictures and pore over a restored copy of the enormous “book of bridges” that catalogued the construction of the line through the Dales.

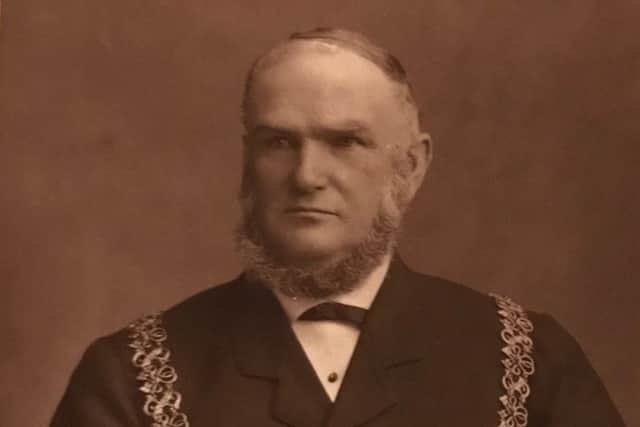

Mrs Tripp, who will speak about the Woodiwiss family history, said her millionaire ancestor had enjoyed something of a rags to riches ride through Victorian England – growing up with eight siblings in a workman’s cottage and working in his father’s rented quarry before becoming a titan of the emerging railways and a two-time mayor of Derby. He had 10 children and died at 54, of rheumatic gout.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIt will be her first visit to Hawes, though she has been to the disused Queensbury railway tunnel between Holmfield and Queensbury in West Yorkshire, which Sir Abraham’s firm also built.

Family legend had it that the unusual surname was derived from the Anglo Saxon for “mad, I think”, she said.

“I’m not a railway buff, but because Abraham’s fortune was made in that way, a lot of people have kept the memories alive,” Mrs Tripp said.

Alan Rhodes, a great great grandson of James Woodiwiss, Sir Abraham’s brother and business partner, was unaware of his genealogy when as a boy he took down the numbers of steam trains near his home at Keighley.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“I discovered only later that there was a connection,” said Mr Rhodes, also a retired teacher.

“Abraham was a giant of the industry. At one point he had 10,000 men working for him.”

Ruth Annison, who has organised the weekend’s event, In Search of Mr Woodiwiss and the Garsdale-Hawes Branch Railway, said it was open to all, but with “a special welcome for descendants of the contractors”.