Memorial at last to the Barnsley pit children time forgot

He had thought his ancestors were from Wales. He did not know that a tragedy on his doorstep had consumed them.

John Hinchliffe, his great-great uncle, was among the 10 miners killed in 1821, in a pit accident at Norcroft, in the heart of the fertile West Riding coalfield.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHis name would have been just a sad footnote on the industry’s role of honour, except that John was only eight when disaster struck.

It has taken until today, exactly 198 years later, for his gravestone to be unveiled.

A campaign to construct a permanent memorial to the victims of Norcroft was begun last year after local historians began to piece together the details of what had happened.

Six children, including two other eight-year-olds, and four adults had died when, at the end of their shift below ground, they climbed into a basket to be hauled back to the surface.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe chain carrying their weight snapped, and they fell 60 yards to the bottom of the shaft.

Such was the acceptance of the occupational hazards of the mines that the next morning the papers mentioned it only briefly, and did not record the age of the victims.

Mr Hinchliffe, who was Wakefield’s Labour MP for 18 years until 2005, had helped lead the campaign to raise enough money for a headstone outside the parish church at Cawthorne, a little over half a mile from the scene, where seven of the bodies were placed in unmarked graves. This evening, he will speak at a service to mark its dedication. Some 200 people from around the area are expected to attend.

“What happened at Norcroft 198 years ago to the day has until very recently been almost totally forgotten,” he said.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“Until now, nothing has marked the 10 fatalities of 1821 or the graves of the six children and one man who lost their lives at Norcroft and are buried at Cawthorne. There have been no gravestones, no memorial, nothing.”

It had been “very moving” to have been in the churchyard two weeks ago when the newly commissioned headstone was put in place,” he added.

But if the tragedy had resonated through the generations in his own family, the effects in the neighbouring community of Tivy Dale were even more profound.

Three brothers, Charles, Robert and Benjamin Eyre, aged 16, 12 and 10, died together. Their sister Charlotte’s husband and his 13-year-old brother were also killed.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“That disaster cost Charlotte her husband, her three young brothers and her brother-in-law,” said Mr Hinchliffe, who served on the board of the National Coal Mining Museum in Wakefield after retiring from the Commons.

A detailed record of what happened is contained in a letter written the day after the disaster by Jeremiah Gilbert, a local preacher, which will be read tonight.

“Eleven men were ascending from one of the pits at Norcroft... and after having nearly reached the top, the brig gave way, and the chains breaking, the whole were unfortunately precipitated to the bottom,” Gilbert wrote to the mother of the one survivor, Thomas Fox.

“The two surviving were Thomas Fox and Thomas Townend (who died shortly afterward), who were so dreadfully fractured that their lives were despaired of.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdGilbert also recorded that a fourth Eyre brother, William, helped retrieve the bodies of his siblings, and quoted onlookers as saying the sight was “the most awful and affecting that they ever saw in the whole of their lives”.

Mr Hinchliffe said: “We can have no way of knowing, in the days long before our modern social security system and compensation for industrial accidents, just how these local families such as the Eyres and Townends continued to manage following the loss of so many of their wage-earners.”

“To the best of my knowledge there is no existing record of any inquests into the deaths, any finding or acceptance of responsibility for what happened perhaps by those working the pit – or any mention of lessons being learned.”

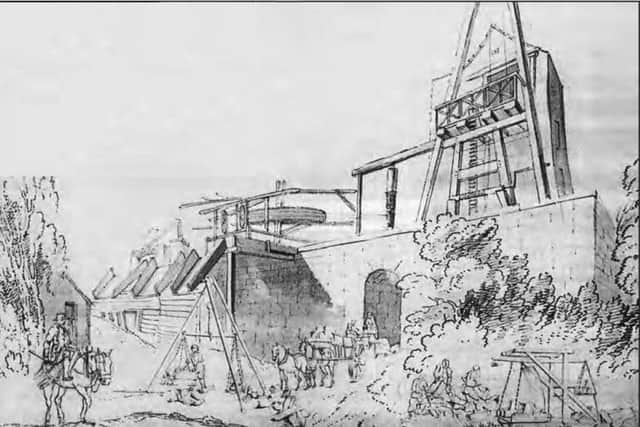

A field of barley now grows at Norcroft where the mineshaft had stood. The deaths of six children, all working underground, prompted no outrage or reform, and it took a second disaster, a mile away at Huskar, to bring change.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdOn that occasion, 17 years later, 26 children – girls and boys aged between seven and 17 – died after heavy rain disabled the winding engine.

A subsequent commission reported that children as young as five had been working in the pits of the West Riding.

“It is to be hoped that those living to the 1840s gained some small comfort that by then there was at least some recognition of the need to take account of the human consequences of the industrial revolution,” said former MP David Hinchliffe.

Tonight’s service at All Saints Church in Cawthorne will begin at 6.30.