‘One of the nation’s most reviled culinary creations’ - we look back at the British Rail sandwich

The butt of countless 1970s jokes, the sandwiches invariably featured – or so the folk memory goes – stale bread curling up at the edges. They have been described as “one of the nation’s most reviled culinary creations”. Even so, eight million of them were sold in 1993.

They offered fillings that now have a distinctly vintage tinge: luncheon meat, brawn, tongue, brisket, cucumber (just cucumber, nothing else), tomato (ditto). “Though we still do boiled ham today,” says Chel Logan, head baker at York’s National Railway Museum, who is standing by to recreate a few retro recipes. Stand by for novel ways of folding boiled ham slices.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

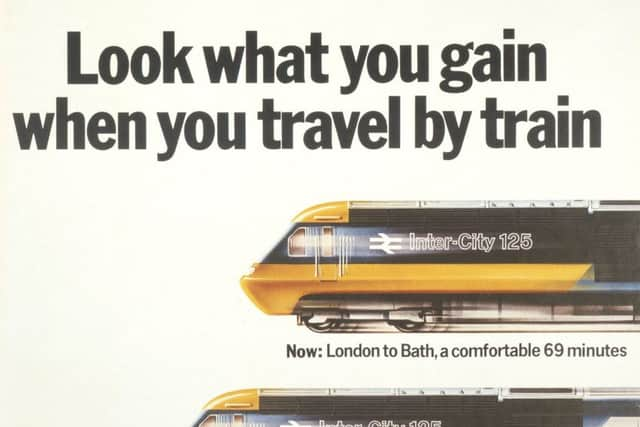

Hide AdAnd why not? We’re very much in Seventies mood as the first Inter-City 125 engine to speed off the production line in 1975 goes on display. Two hundred were built up to 1982, and they’re instantly recognisable. Travelling at 125mph, they were nicknamed “The Flying Banana” thanks to their yellow (and blue) livery.

They’ve been the backbone of the railway network for the past 40 years, powering the High Speed Trains that were once the fastest in Europe and held the world speed record for diesels (148 mph). Crucially, they were more comfortable than the trains they replaced. “A standard no other railway in the world will offer you,” was the boast.

Now, however, these “power cars”, as they’re more correctly known, are being gradually withdrawn and the first of them can take its place among the other historic locos on show at the museum. It may not have the sheer glamour and charisma of, say, the Mallard (also on show), but, with its wedge-shaped nose cone, it still looks streamlined and “modern” 40 years on.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdRepainted in its original colours, this sleek, gleaming beast is the most recently built engine on show. It offers a fine contrast to the oldest: Stephenson’s legendary Rocket. All clanking pistons and rivets you wouldn’t argue with, the pioneer engine was built in 1829 and was capable of travelling at 30mph.

The museum’s 125 is named after its designer Sir Kenneth Grange, who for decades has helped define functional style with his Anglepoise lamps, Kenwood mixers, Morphy Richards irons and Kodak Brownie and Instamatic cameras.

“The 125 was part of a complete design makeover of the railway system – top to bottom: uniforms, menus, clock faces, everything,” says Bob Gwynne, the museum’s associate curator. “It was the railways’ fightback against the big car economy; they needed to see off the growth of the motorway network in the 1970s.

“Most people’s aspiration was to get a car – the company car was a badge of honour - and people could also fly from Manchester to London. But the 125 changed people’s attitude to rail. They saw it as go-ahead, dramatic and radically modern.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAs a rail slogan proclaimed: “This is the age of the train.” Whether or not, it was certainly the age of the slogan. They came thick and fast in 125 marketing. Let the train take the strain... We’re getting there... The changing shape of rail...The Journey Shrinker... Inter-City 125 makes the going easier.

“See a Friend This Weekend,” urged a poster, with a picture of an ecstatically happy blonde nuzzling against the tweed jacket worn by her husband/boyfriend/lover.

Badges boasted: “I’ve been on the 125!” And there was a plug for the Travellers-Fare menus brought in by celebrity chef Prue Leith (also of Bake Off). “The Journey Fillers” was the slogan, accompanied by images of buffet car fare delivered on plastic trays – burger and chips; sausage, bacon and egg; toasted sandwiches (we’re coming to the sandwiches: Chel Logan is ready and waiting).

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdPhilip Benham, BR area manager based in York from 1982 to 1986, recalls those pioneer days. “I was surprised that there were people living in the York area who commuted to London every day,” he says. “We had one passenger who commuted from Bridlington to London. He must have got up at 4.30am and got home at 10.30pm. Looking back, the 125 was a step-change in the history of railways.”

The conversation turns – as rail enthusiasts’ conversation so often does – to Dr Richard Beeching and his 1963 Report, which recommended the closure of 2,300 stations and 5,000 miles of the nation’s 18,000-mile rail network.

“Beeching is misunderstood,” says Gwynne decisively. “He wrote a report for the government; he didn’t close any railways. He said they needed to concentrate on what they were good at – inter-city services and bulk loads.

“There’s a nostalgia for the old sleepy branch lines. The fact is that people were deserting the trains in droves. It was all about ‘driving along in my automobile’. So the 125 is unbelievably important because it basically brought people back to rail and allowed it to survive.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

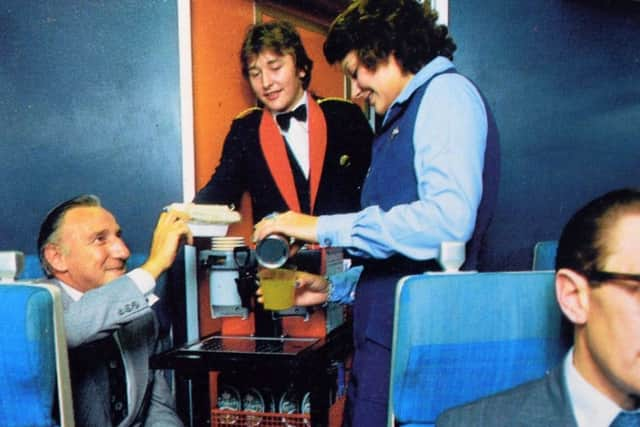

Hide AdAnd to offer food-in-motion on what was marketed as “The Haute Cuisine Train”. Travellers-Fare gave passengers two options – eat in the restaurant car or buy something at the buffet bar (“an attractive ‘pub-on-wheels’”) .

The restaurant’s First Class menu – which can prompt sighs of nostalgic rapture from passengers who remember it – included kippers for breakfast, and asparagus soup and gammon steak with glazed peach and “golden fried chipped potatoes” for lunch or dinner. Children under 13 paid half-price and, as the menu said, “Diners are requested to refrain from smoking immediately prior to and during the course of the meal.”

Passengers could, however, opt for a buffet menu of sandwiches and filled rolls. Catering staff had to follow exhaustively meticulous preparation instructions in the vast “Corporate Identity Manual” issued in 1971.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThis guide to making the perfect sandwich had a six-point plan which Chel Logan is gamely following, point by point. “It would always be white-sliced bread,” he says, as he reads Point One: “Cream the butter to a smooth and even consistency to facilitate spreading.” Around one-sixth of an ounce should be used, the manual said.

Nothing was left to chance: “Place approximately two-thirds of the filling to cover the whole surface of the bread... Place the remaining third of the filling diagonally across the bread where the cut is to be made.” As Philip Benham says: “If you put the filling in the middle of the sandwich, it looks as though there’s more.” A sandwich using just two slices of ham would appear to have three. Fiendish.

And when the sandwich was finished: “Sandwiches will be wrapped. Every effort should be made to display them in such a way as to show the filling.”

As for toast: “A cut 42-ounce catering loaf giving slices of approximately four inches by four inches is recommended.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdLogan makes me a cheese and tomato sandwich (wrapped in cellophane); simple it may be but it’s surprisingly fresh and tasty. And he scans the Seventies sandwich menu.

“None of the focaccia with roasted peppers we do these days,” he smiles and shows off the museum’s 2019 sandwich display. Chicken ciabatta, vegan salad, hummus focaccia... what would Seventies commuters have made of them?

As I leave, I have another look at Stephenson’s Rocket. It’s surrounded by awestruck rail enthusiasts taking photographs. “What an astonishing achievement this was,” says one. It really was Rocket science.