The enduring story of English pubs, how they have changed and why they are so important

The Moon Under Water may have been fictional, a composite of the author’s favourite London pubs, but Orwell was precise in what it was like – a small establishment with no music, china pots with creamy stout and most importantly, a convivial atmosphere.

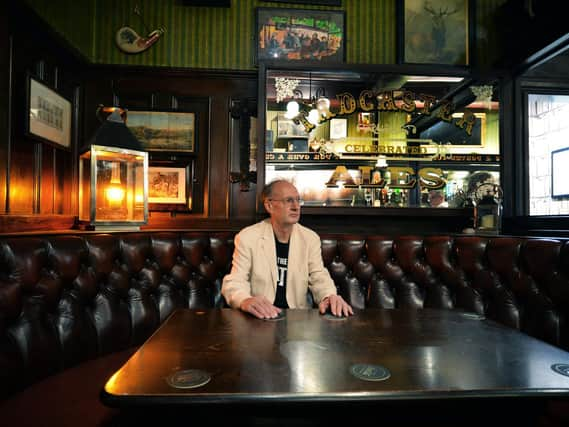

Drinking dens in one shape or another have been an intrinsic part of our social fabric for centuries and their story and evolution is told in historian Paul Jennings’ meticulously researched book The Local – A History of the English Pub which has been reissued and updated (it was originally published in 2007) to look at the impact of the pandemic.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIt charts the story of pubs from the 18th century to the present day taking in the early coaching inns and the Victorian backstreet beerhouses, right up to the modern gastro pubs that we recognise today.

The pub landscape is constantly changing and is a tale of contrasting fortunes. On the one hand, many of what we might recognise as traditional boozers, the kind that used to pepper our towns and cities, have disappeared, but at the same time the number of so-called micro pubs and craft ale houses has mushroomed.

“There’s a greater variety in places where you can drink alcohol but there are fewer places you would identify as pubs,” says Jennings.

“Pubs have been in decline for a long time and numbers have been going down in particular since the 1950s. It’s to do with slum clearances and changing populations, all kinds of things.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdJennings says the number of pubs in Bradford, where he grew up, has dwindled. “If you go to some of the main thoroughfares like Manchester Road there used to be something like 35 pubs along the route and there are a handful now, if that.”

It’s a similar story across many northern towns and cities. “All those working class men who worked in factories, or foundries and coal mines, were the mainstay of many pubs and that lifestyle has gone. The neighbourhoods that once had pubs on every corner have gone, people’s leisure habits have changed and the demographics have changed.”

It was while teaching adult education courses in Bradford that Jennings started running a class looking at the history of English pubs, which became the kernel of the idea for the book.

“I’ve always liked going to pubs and I worked in one, The White Lion, up in the Lake District for a time, so it’s something I’ve always been interested in.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIt’s easy to wallow in misty-eyed nostalgia for the pubs that have gone to the great tap room in the sky, but the truth is there used to be a lot of grotty places. “I remember going into pubs and waves of hostility would travel across the room towards you,” says Jennings.

Pubs, he feels, are better now by and large, because they have to be. “People’s expectations are so much higher. The average person doesn’t want to sit in some dingy pub full of cigarette smoke. And there are some pubs that are a pleasure just to go in, like Whitelocks in Leeds, or the Adelphi across the bridge.”

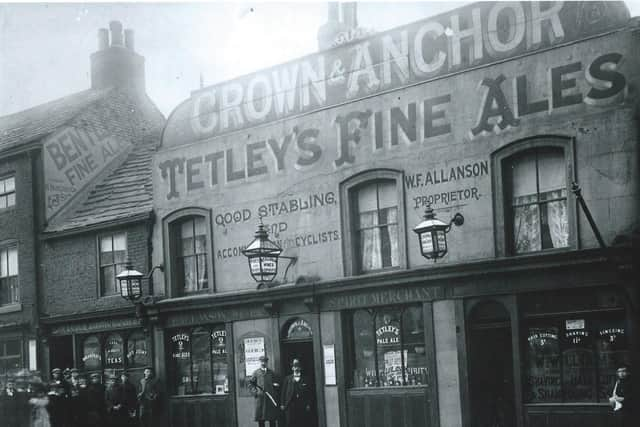

The story of public houses in this country has several roots. “One of them is the coaching inn of which there aren’t many left these days. Places on the old Great North Road like Doncaster and Wetherby were full of inns for travellers, and if you think of some of towns like Thirsk, Richmond, or Knaresborough, the marketplace would have been full of inns, not just for travellers but people coming to market,” says Jennings.

The coaching inns began to wane with the advent of the railway and development of railway hotels in towns and cities, but they weren’t the first precursors to pubs.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“The most common drinking places from medieval times were the local ale houses, which might just be somebody’s front room or a cottage where they sold beer to make an extra living.

“Then in the 18th century you had the start of the gin craze and all these gin shops, usually in bigger cities, which gradually developed into something identified as the public house.”

Another key moment came in 1830 with the introductions of the Beer House Act, which meant any householder could obtain a licence to sell beer. “The consequence of that was you had thousands and thousands of these little beer houses that could only sell beer.”

It wasn’t until the 1860s and 70s when drinking establishments began to get called pubs. “Other countries have drinking places. Ireland has pubs, but they’re a bit different. A lot of them were run and owned by a proprietor which is why you find so many called ‘Finnegans’ and ‘Murphys’. Scotland has pubs and bars but generally they’re not quite the same. America had its saloons and France its cafes, it’s the way they evolved from those other institutions.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAttitudes to pubs have changed over the years. “There was vast opposition in Victorian times with the temperance movement and you go from that to the pub being a perfectly acceptable place to go. Today, women are regular pub goers, but in the past they were a minority. Now you get families going and Wetherspoons have done good business catering to families as well as other pub goers.”

When the smoking ban came in 2007, many believed it would kill off pubs. “I’ve always been of the view, though I can’t prove this empirically, that it had less effect than some people have claimed,” says Jennings. “Pubs that were on their way out, the dingy backstreet ones, were precisely the ones that tended to be full of smokers.”

Similar predictions have been made about the impact of the pandemic, though Jennings says it’s hard to gauge. “I suspect what we’ll see is a continuation of the trends that were there before. Some pubs have shut and won’t reopen, on the other hand new ones have opened.

“There will be a net loss but whether this number is greater than if the pandemic had never happened I rather doubt,” he says.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“What was unprecedented was the fact they were forced to close completely. Even in the flu pandemic after the First World War, when a lot more people died, they didn’t shut pubs completely. Even if you go back to the plagues of the 17th century they had curfews but they didn’t close ale houses down.”

So what does the future hold for the English boozer?

“I think we’re likely to see a continuation of where we are now. It will keep being diverse because the word ‘pub’ contains such an array of different establishments, from somewhere like the Duck and Drake in Leeds, a real ale pub with an emphasis on music at night, to Starlings in Harrogate, which is basically a restaurant that sells real ale, to these tiny little craft beer places.

“Drinking places will continue to be an important part of people’s leisure time but the old kind of pub world has gone and won’t come back because we lead different lives.”

The Local – A History of the English Pub, published by the History Press, is out now.