Going loco in a triumphant era for the railways

Eighty years ago cloth-capped and boiler-suited workers of all ages at Doncaster’s railway works, The Plant, were getting ready for a momentous occasion.

For months, small teams of riveters, blacksmiths, wheelwrights, boiler makers, brass finishers, sheet metal workers and a whole lot more had worked on a very special project. They lived in Coronation Street-type houses that radiated from The Plant and were full of enthusiasm as they had helped give birth to a very special steam locomotive.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdEvery Doncaster Plant man had put their patience and skill, not to mention long, unstinting, sweaty hours into the job for one man – Sir Nigel Gresley. Based in London, he was Chief Mechanical Engineer of the LNER, which employed thousands of hands up and down the East Coast Main Line. his design for this exceptional locomotive was the result of years of experimentation.

Gresley, born in Edinburgh, yet raised in Derbyshire, the son of a vicar, had spent many happy hours working atThe Plant during the first quarter of the 20th century. First he was Carriage & Wagon Superintendent, then Locomotive Superintendent, forging a unique and special relationship with the workforce which at one time numbered over 6,000.

In the early 1920s the Doncaster men and Gresley had built the world-famous Flying Scotsman, which is much celebrated today and still gathers vast crowds when up and running, trailing behind it clouds of steam.

Polished to perfection, at the Doncaster engine cleaners’ loving hands, the new engine, when unveiled in May 1934, was the largest ever built in Britain to haul passenger trains. Boasting eight massive driving wheels and a yawning firebox, it was constructed to work in Scotland, between Edinburgh and Aberdeen, on the LNER’s sleeping carriage traffic.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdExisting locomotives assigned to work were buckling under the strain. The stretch was particularly torturous, having an abundance of sharp curves, steep gradients and speed restrictions and shouted out for a powerful engine to keep to the scheduled times.

Thus, the new locomotive was aptly named Cock o’ the North, taking its name from General George Duncan Gordon, 5th Duke of Gordon, (1770 - 1836).

Naturally, when unveiled at exhibitions in Doncaster and Stratford, Cock o’ the North caused quite a stir in the railway world. A number of trials up and down sections of the East Coast Main Line were also carried out and the engine achieved quite impressive results.

In his work, Gresley was influenced by a number of eminent foreign railway engineers, perhaps most notably a Frenchman named André Chapelon. This man built a test plant at Vitry-sur-Seine, near Paris, to obtain data about locomotive performances. Gresley had advocated that such a facility should be provided in Britain, but this did not occur until 1948. Nevertheless, eager to show off the smart green liveried engine, exquisitely lined and with LNER emblazoned on the enormous tender, Gresley had it transported by ship to the French test plant. Wagons brimming full of Yorkshire Main coal also went along too, ensuring the engine was fed the ‘correct’ coal .

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdUnfortunately, the colossal locomotive encountered a number of problems at the centre, and the tests were cut short. But Cock o’ the North did run some relatively successful trials on the French line between Tours and Orléans.

Returning to the UK, the locomotive was put to work in Scotland, eventually being joined in service by five others built to similar specifications and grouped together in the P2 Class.

Gresley was beginning to take further strides in his locomotive designs by the late 1930s. His greatest moment occurred in 1938 when the streamlined Doncaster-built Mallard achieved the world speed record for steam locomotives of 125.88 mph. At this time Cock o’ the North also acquired a streamlined front end like Mallard.

When Gresley died in 1941, Edward Thompson became the LNER’s Chief Mechanical Engineer. As a result, and after a number of mechanical and operating problems, he decided to rebuild Cock o’ the North and its other P2 classmates.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe engine was altered beyond recognition in September 1944, ending a great period of innovation in locomotive design on the LNER.

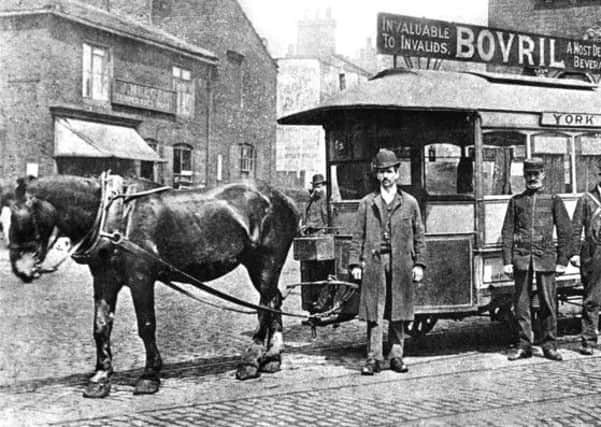

Yorkshire’s streetcars of desire and the horses that pulled them

It’s always fascinating comparing former modes of road transport with today’s modern buses. Let’s take horse-drawn trams.

Despite having no heating in winter, air conditioning in summer and a whole range of other provisions for comfort and safety, horse cars were a great improvement on the omnibus as the low rolling resistance of metal wheels on iron or steel rails allowed the animals to haul a greater load for a given effort and gave a smoother ride.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe first rail passenger services in the world were started in 1807 by the Oystermouth Railway in Wales. The first streetcar in the United States appeared on November 26 1832. These were hauled by horses and sometimes mules, usually two as a team and rarely, other animals were tried.

It took until 1860 before horse trams were introduced to Britain, in Birkenhead. It was the work of American, George Francis Train. He was subsequently jailed for “breaking and injuring” the highway when he next tried to lay the first tram tracks on the roads of London.

An 1870 Act of Parliament set the legal requirements for companies operating horse-drawn tramways in Britain for the next three decades.

After much debate, between Leeds Corporation and various companies, permission was given to William and Daniel Busby to operate the city’s first horse-drawn tramway route on Saturday, 16 September 1871. It ran from the Briggate end of Boar Lane to the Oak Inn, Headingley.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdInitially, the Headingley service employed four, four wheel, double-deck cars, with 15’ 3’’ long bodies, seating 20 cramped inside and 20 braving the elements outside. They cars were built by the Birkenhead company of George Starbuck.

Each Headingely tram was harnessed to three horses with an additional one sometimes used for the trudge up Cookridge Street. A second route was extended from Boar Lane to the Star and Garter public house, Commercial Road in April 1872.

To boost receipts, carriages were run each way every morning and every evening in the week (Sundays, Christmas Day and Good Friday always excepted) especially for artisans, mechanics and daily labourers.

Around August 1872 the Busbys transferred their undertaking to a new company, the Leeds Tramway Company which opened further horse tram routes to Hunslet, York Road, Chapeltown, Meanwood and New Wortley.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdBy 1876 there were 51 horse trams in operation in Leeds: 30 single-deck and 21 double-deck.

Early tramcar double-deckers had removable ladders for access to the top deck.

The operation of horse cars was not without problems. Horses could only work so many daily hours, had to be housed, groomed, fed and cared for and that’s not forgetting the vast amounts of manure they produced. The Leeds horses – mainly Irish – were bought when around five or six years old. The cost of a tram horse was between £30 and £35.

After a long, bitter, legal dispute, Leeds Corporation decided to begin operating all the tramways themselves from 1 August 1896. In time, a switch was made from horse and steam trams to the more practical electric trams and the city’s first electric route, extending from Roundhay to Kirkstall, was officially opened on 29 July 1897.

Horse traction ceased in Leeds after 30 years on October 13 1901.

• Did you or any family members or ancestors work for Leeds City Transport? If so, and you have some stories and pictures,