How Leeds built its reputation on Victorian grandeur

According to Christopher Webster, editor of the excellent Building a Great Victorian City (2011), the story of Leeds and its Victorian architecture was one of remarkable development. “As an adjunct to commercial, manufacturing and population change came a stunning array of new buildings, sufficiently grand to reflect the town’s achievements as well as its aspirations,” states Webster.

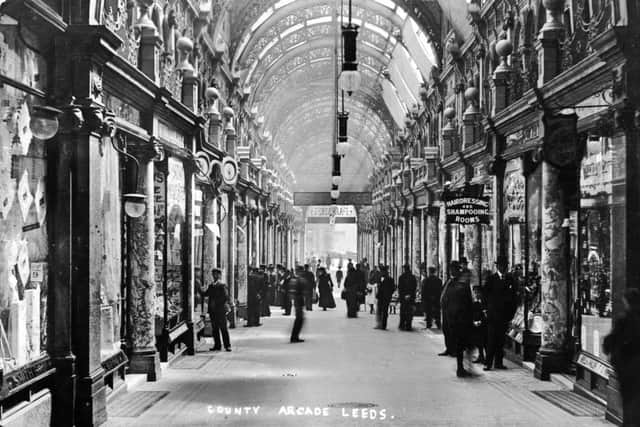

Responsible for construction work on countless successful contracts for churches, railway stations, schools and town halls in Yorkshire, and beyond, was the firm of William Nicholson & Son. In Leeds, the company is especially noted for erecting the Queens Hotel, Tetley’s Brewery, Leeds General Infirmary and the County Arcade. A speciality of the firm was building strong-rooms and halls for major banks, as well as the Tower of London’s Jewel House in 1953.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdFounder of the business was William Nicholson, who came from Swaledale, where he had worked with his father, a wheelwright and joiner. He established himself in Leeds and, after working with a partner, welcomed his son, also called William, into the business. The pair’s reputation as master builders grew and they took advantage of the days of the industrial revolution, when railways were snaking everywhere, and banks were establishing outposts in many parts of the country.

The company’s first business premises were in Salem Place, adjacent to Tetley’s Brewery. Over the ensuing years, Nicholson’s would undertake much work for the brewers, besides receiving a cheque every month for jobs undertaken for the Midland Railway Company. Nicholson’s were also continually employed by the Great Northern Railway Company.

Within 15 years of establishing the business, the work rapidly increased and the firm’s reputation extended beyond Yorkshire. But, the firm did experience difficulties, especially when a viaduct that was built for the Midland Railway settled down over one foot from end to end, owing to coal workings subsiding for its whole length, but fortunately no arch was broken.

Company wages in those early days were around 41/2d. per hour for an unskilled labourer, and 61/2d. for a skilled man.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdMachinery, too, was absent. Timber was cut into planks by hand over what was called a saw pit, in which men used a saw five or six feet long, one man standing at the top and the other at the bottom. At that time there were no quantity surveyors. Each builder had, therefore, to take off his own quantities from the plans and, as might be imagined, when a number of men were trying to do this at the same time, and from the same plan, there was much confusion and delay.

A trade union was established in the firm following the advice of William Nicholson II. He believed this would be beneficial to the workers, and provide a representative body for negotiations regarding wages and conditions. It was noted that on two of the largest contracts undertaken in 1850 there were 22 strikes; the majority of these beginning without any notice. Thereafter, the relations between the Nicholson family and the workforce continued to be friendly and cordial. One man was noted as notching up 62 years’ service while others went past the 50-year mark. It became a well-known phrase that if someone served their apprenticeship at Nicholson’s they could get a job anywhere in the trade.

In the mid-Victorian era the firm fully established its reputation. G. Corson, a well-known leading Leeds architect, insisted on all his buildings being erected substantially, and with the best workmanship and materials obtainable. Nicholson’s brought to life many of his, and other architect’s, plans. Every client believed that it was the truest economy to build solidly. The motto of the Nicholson family was always: “What is worth doing is worth doing well,” and the permanency of the buildings erected during the 19th century is a proof that they practised what they preached. The company was especially noted for its commitment to meet almost impossible deadlines.

In subsequent years a fire completely destroyed Nicholson’s Prospect Works and the business was transferred to Island Wharf. A further blaze meant a move to Chadwick Street. With further family members at the helm – and all called William –Nicholson’s thrived into the 20th century.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIn time, the company began to install the first generation of ATMs for banks. However, as Britain suffered economic turmoil in the 1980s, the company’s fortunes began to wane. A combination of circumstances, notably the decision of banks to move away from traditional methods of conducting business as banking deregulation took hold, meant that profits tumbled. Shortly afterwards Nicholson’s ceased to trade.