How Yorkshire celebrated the 1950s predecessor to ‘Festival of Brexit’

One of Theresa May’s more intriguing legacies is the grandly named Festival of Great Britain and Northern Ireland scheduled for 2022. Backed by £120m of Government money, it will celebrate the best of the UK’s business, technology, arts and sport. And so, the theory goes, cheer us all up.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdPerhaps inevitably, it has been mocked as a “Festival of Brexit Britain”, particularly in the light of Westminster’s seemingly unending political shilly-shallying and scheming, its shenanigans and skulduggery.

Whether or not it deserves the mockery, it’s an obvious echo of the 1951 Festival of Britain launched by the Labour government as “a tonic for the nation”.

After the hardships of the Second World War, with austerity still grinding on, the festival was conceived as a morale booster – “the people giving themselves a pat on the back” as politician Herbert Morrison, its driving spirit, said.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIt celebrated the nation’s past achievements and looked forward to its bright new future – as an event at Sheffield Hallam University next week (Friday Nov 22) will explore.

The Festival of Britain Archive Afternoon, featuring displays and talks, will draw on the university’s store of festival memorabilia – 2,000 items in all, the biggest such collection outside London. Donated by the Daily Mirror in the 1970s and subsequently expanded, it ranges wide, including postcards, a teapot, a pocket watch, plastic toys, a letter opener, bars of soap and a “magic money box” (“opens when 30 pennies are saved”).

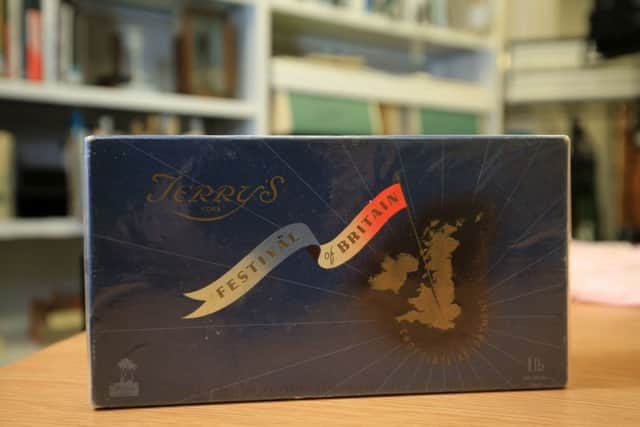

There’s a vinyl handbag featuring London landmarks, a Terry’s chocolate box (empty), posters, letters, booklets, glassware, medals, a powder compact with fragrant traces of Fifties powder still lingering, copies of the enticingly named Festival Concrete Quarterly, a swimsuited Miss Great Britain doll (a souvenir of the Festival’s bikini contest, which spawned the Miss World competition) and a fetching pair of pink embroidered knickers.

Most of this memorabilia – even the knickers - is emblazoned with the festival’s distinctive logo, featuring a helmeted profile of Britannia at the centre of a compass-like star, fluttering with patriotically red, white and blue bunting, as seen on a souvenir compact inset left.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“The festival was England’s first big event after the war, so there was a lot of interest,” says Andrew Jackson from the Twentieth Century Society, which is dedicated to conserving and celebrating 20th century buildings and has organised the archive afternoon.

Over five months, some 8.5 million people visited the festival’s main site – an estate of two dozen modernist pavilions on London’s newly created South Bank: buildings that brought flair and colour to an often grey, utilitarian post-war world.

They showcased all that was perceived to be great about Britain: engineering, farming, sport, railways, the seaside, the Pennines, radio telescopes, bed-sitting rooms and much more. At the opening ceremony in May 1951, George VI – looking drawn just nine months before his death – expressed a hope that “the vast range of modern knowledge which is here shown may be turned from destructive to peaceful ends, so that all people, as this century goes on, may be lifted to greater happiness.”

The festival – described by one commentator as a “soft-Soviet” project – was designed to show off Britain both to its own people and to the rest of the world. By the end of its run in October, though, only two per cent of visitors had come from overseas.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThey found a sort of educational fairground of British life. It took in mannequins of Captain Cook, displays about atomic energy and a Nell Gwynne lookalike selling oranges. As Richard Bradley, Hallam’s special collections officer, points out, the festival had a curious approach. “Half of it was cutting-edge-modern and half of it was twee Merrie-England design.” Dependably outspoken, the conductor Sir Thomas Beecham was in a minority when he dismissed the whole venture as “a monumental piece of imbecility and iniquity”.

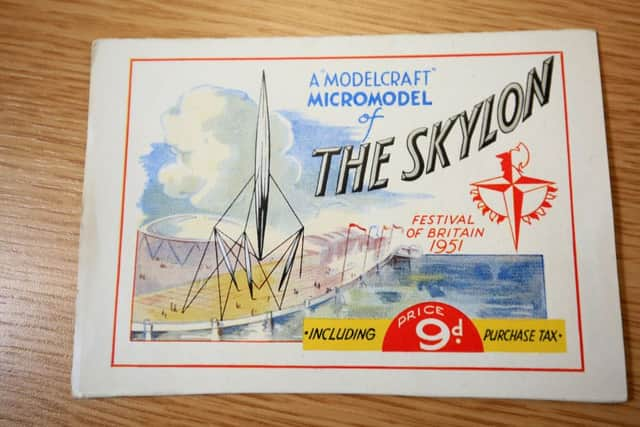

The South Bank site was dominated by the colossal flying saucer-like Dome of Discovery. The most striking structure, however, was the Skylon, a sleek cigar-like 300ft steel and aluminium sculpture with a hint of Dan Dare about it. The joke was that it was like the British economy: it had no visible means of support.

Today, only the Royal Festival Hall, the first new public building since the war, survives; the rest was razed. “The Labour Party thought the festival would be a big vote winner for them, but they didn’t get in at the next election and Churchill had the site dismantled,” says Bradley.

The London jamboree has always been the festival’s best-documented feature, but events were also staged across the country, with local celebrations in 17,000 towns and villages. Some, it must be said, were on a modest scale.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdBeverley planned a new public garden “with dwarf wall”. Knottingley’s programme included a mounted police display, a sports day and Punch and Judy. Whitby’s featured a Goathland Hunt Point-to-Point, a Sports Olympiad (North Yorkshire style) and a Road Courtesy Week.

In Leeds, events attracted 145,000 people over three weeks. Footage in the Yorkshire Film Archive shows crowds milling around a Lancaster bomber and whooping it up on carousels and swing boats at a funfair. York staged an ambitious programme with a regatta, a river carnival, a Georgian ball, band concerts, folk dancing and a production of the now little-remembered “Yorkshire operetta” Highwayman Love by the Yorkshire Amateur Operatic and Drama Society.

More significant was the first major staging since the 16th century of York’s cycle of mystery plays, launching a tradition that has become a highlight of Yorkshire’s cultural life. The programme warned that compressing 48 plays into three hours meant a fair bit of cutting. Nonetheless, the plays were seen by 26,000 people and were described as “the most widely applauded festival event in the country”.

York also hosted an impressive series of orchestral concerts by the London Philharmonic, the Halle and the short-lived Leeds-based Yorkshire Symphony Orchestra. Conductors included Sir John Barbirolli, Sir Adrian Boult and the inspirational Victor de Sabata. Elisabeth Schwarzkoff and Kathleen Ferrier were among the soloists, and choirs from Huddersfield, Leeds and Sheffield sang in the Minster.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdOrganisers made every effort to spread the festival spirit. Hull was among the ports of call for HMS Campania, a “festival ship” loaded with displays, on a voyage taking in Southampton, Dundee, Newcastle, Plymouth, Bristol, Cardiff, Belfast, Birkenhead and Glasgow. In Hull it attracted 88,000 people. The ship’s official programme included an advert for Kwells (“prevent travel sickness”). Perhaps ill-advisedly, the tablets were billed as having “The D-Day Formula”.

All told, the Festival was a massive national undertaking. As Hallam archivist Heidi Sidwell says : “You can’t imagine anything on a similar scale today.”

Asked to choose her favourite item from the archive (which can be viewed by appointment), she chooses a headscarf decorated with images of great London buildings. “It’s colourful and functional,” she says of the scarf: the 1951 ethos in a nutshell.

Andrew Jackson goes for an attractively packaged cardboard model of the Skylon, on sale for ninepence (about 4p) “including purchase tax”. “It would have been a great souvenir,” he says. “You could just slip it in your pocket if you went to London for the day.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdRichard Bradley thinks hard about his favourite item. “I don’t know if it’s my favourite, but this is what made me laugh most,” he says, handing over a typed letter sent by the Musicians Union to festival organisers in 1950. It thundered: “We are particularly disturbed by reports that it is intended to include foreign orchestras, conductors and soloists.” Brexit was in the air even then.

Festival of Britain Archive Afternoon at Sheffield Hallam University: November 22 (2pm to 4pm). Tickets (limited): £10. See www.c20society.org.uk. For more information you can go to this link libguides.shu.ac.uk/specialcollection/festival