South of York city centre, halfway to the city’s main university campus lies The Retreat.

It’s a pioneering mental health facility set in lush green grounds and flanked by the Walmgate Stray, a stomping ground for dog walkers and, at the right time of year, a docile herd of cows.

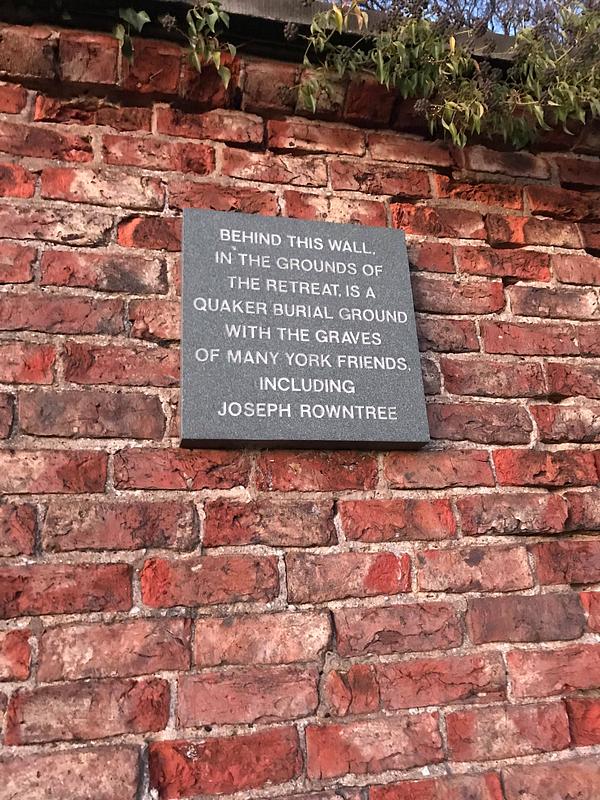

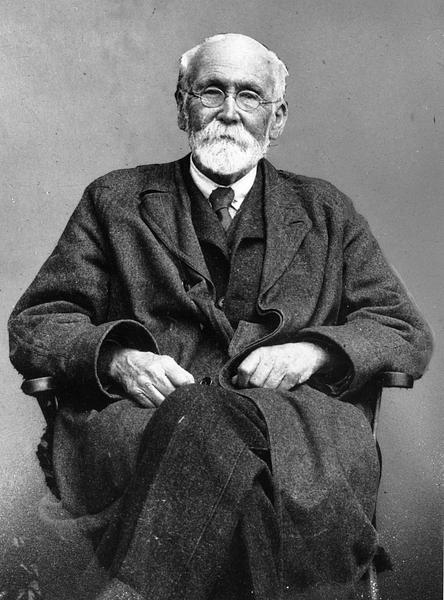

Within The Retreat’s peaceful walls is a small Quaker cemetery. It’s the final resting place of Yorkshire-born Joseph Rowntree, the man who governed the forward-thinking facility for more than 40 years.

His simple headstone assumes an equal position among several others marking the lives of York Quakers, and a large brick wall forms a partition between the cemetery and the Stray.

A small plaque on the other side of the wall is the only clue to the most attentive of passers-by that Joseph Rowntree is buried here.

For a man whose family legacy includes pioneering eight-hour working days and campaigning for a national minimum wage, lifting thousands out of poverty and making foundational contributions to the British welfare state and NHS, it’s a startlingly humble tribute.

That’s not to say it’s unfitting, however. The trusts bearing Joseph Rowntree’s name are still prominent in public life, but few - especially outside of York - know much about the man himself.

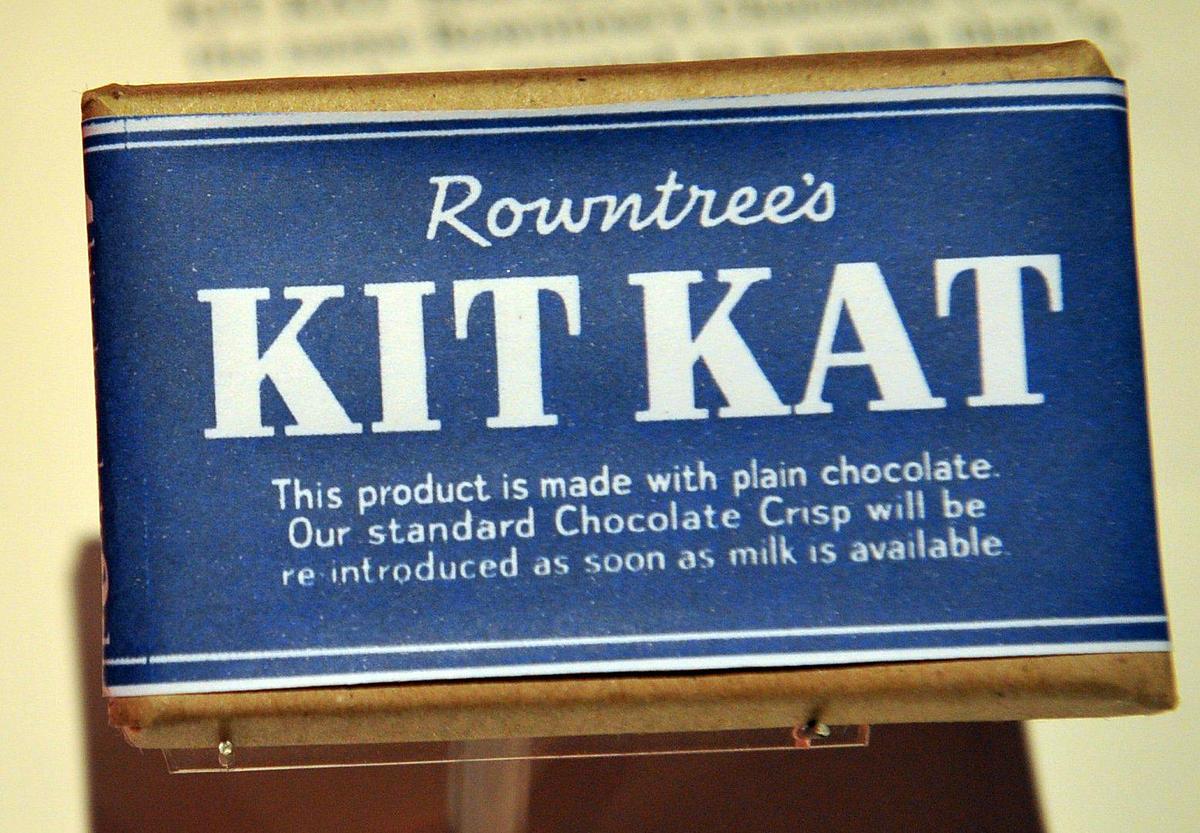

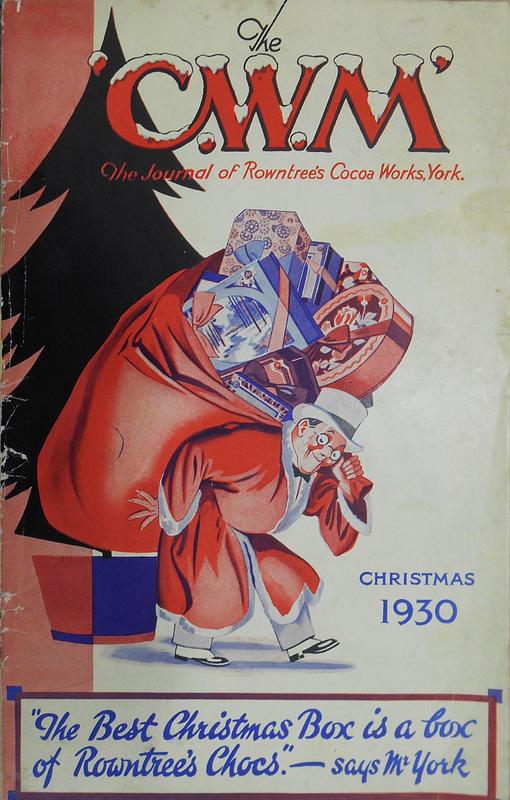

To older generations, ‘Rowntree’ conjures up the big name confectionary brands - Kitkats, Fruit Pastilles - that made the family their fortunes. Since the Nestlé takeover in 1988, the name means even less to younger generations.

Thanks to their international success in the business world, the Rowntree family’s phenomenal influence on Britain beyond their confectionary often falls under the radar. Given the family’s characteristic Quaker modesty, it’s not a fact that they would bemoan.

Yet over 100 years ago, the Rowntrees took a radical stand against the dire Victorian conditions of the factory and the cruel condemnation of the poor, driven by a desire to make society a better place. Miles ahead of their time, they promoted liberal policies and ideas on everything from the treatment of mental health conditions to safe and sanitary housing.

Joseph Rowntree was once called “one of Britain's greatest and most interesting philanthropists” - but “most forgotten” could easily be added to the list.

But in a modern Britain once again plagued by poverty, a housing crisis and at times unsafe working conditions, the Rowntrees’ altruistic, radical approach to solving society’s ills may be more important to remember today than ever before.

Chocolate and Quakerism

‘Employees should never be regarded as cogs in a machine’

Throughout the late 19th and early 20th century, Britain’s confectionary industry was dominated by Quaker families, which was due - at least in part - to the religion’s aversion to alcohol.

Drinking chocolate was viewed by Quakers as a alternative to booze, and it was this simple belief that spawned the huge competing chocolate factories that would go on to inspire Roald Dahl’s beloved Charlie and the Chocolate Factory.

While everlasting gobstoppers and three-course dinner chewing gum are certainly figments of Dahl’s imagination, moles infiltrating the likes of Terrys and Rowntrees to steal recipes was not.

The Rowntrees’ involvement in the chocolate industry began with Henry Isaac Rowntree’s purchase of a cocoa business from the Quaker Tuke family in 1862.

He founded what would later become the Rowntree confectionery business and was joined by his brother, Joseph in 1869.

After Henry’s death in 1883, Joseph took over the business and designed a factory on the firm premise that employees “should never merely be regarded as cogs in an industrial machine, but rather as fellow workers in a great industry”.

In an era where poor working and living conditions for factory workers were endemic across the country, Joseph, like his contemporaries, could easily have built a factory in the usual profit-above-all vein.

Instead, during a time when children under ten could still legally work in Britain’s factories, he designed a business in which employees gained access to a library, a free education, a staff canteen, swimming pool and theatre.

Bridget Morris, executive director of York’s Rowntree Society, is quick to point out that these amenities were “not just added extras” to the Rowntrees: “They were part of the belief that to be a good worker in the factory you had to be well-rounded, you have to engage in other things in your life as well [as work].”

By 1943 the average working week for a UK manual worker was still 53 hours, and it wasn’t until 1993 that the EU Working Time Directive limited the amount of hours employees could be made to work in a week. Yet almost 100 years earlier in 1896, the five-day, eight-hour working week had already been introduced for Rowntree employees.

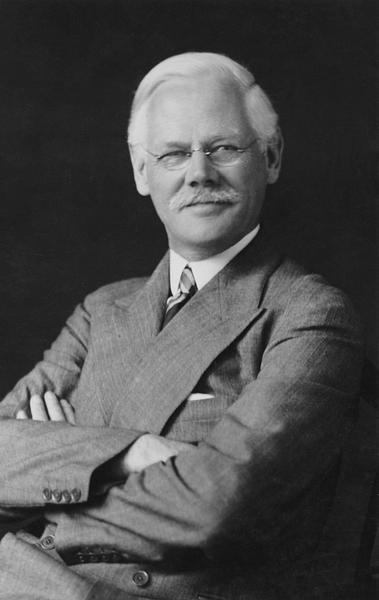

In 1897, the Rowntree business moved to the Cocoa Works on Haxby Road, York, and Benjamin Seebohm Rowntree - Joseph’s son - was made director of the company.

Driven by the same passion for social justice as his father, Seebohm continued to revolutionise working conditions in the factory, employing a doctor and dentist to examine employees for free in 1904, a pension scheme in 1906, works councils in 1919, and a profit-sharing scheme in 1923.

Later on, the high wages at the Rowntree factory became one of - if not the - most profitable ways for women to gain a degree of financial independence in York.

From slums to schools

The model village in a struggling city

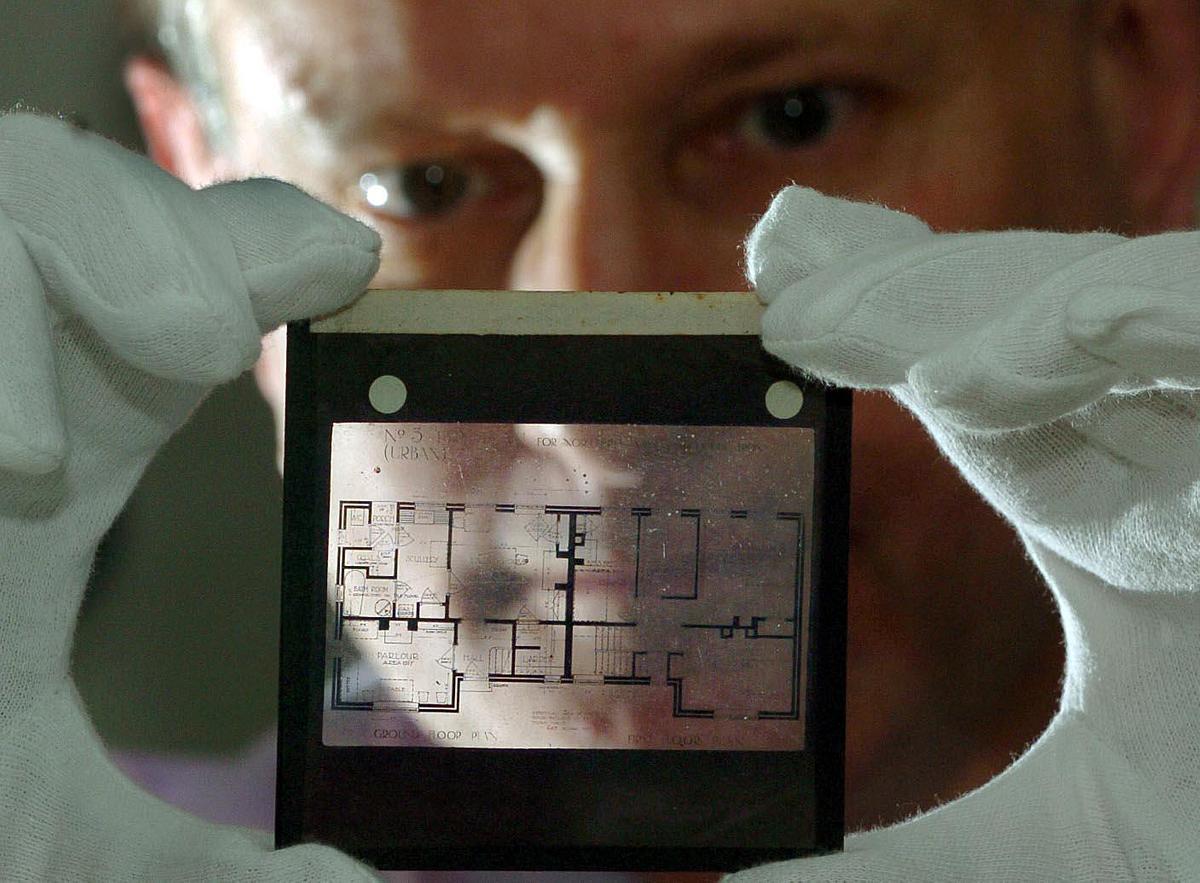

Just a short walk from the Cocoa Works’ former location on Haxby Road is the village of New Earswick. Kitted out with a modest row of shops, a community centre and local schools, it looks much like any other English village - bar a local pub.

This missing pub is perhaps the biggest remaining visual giveaway of the Rowntree family’s influence here.

In 1901, it was Joseph Rowntree who purchased land to build New Earswick, a mixed-income community “for the improvement of the condition of the working classes...by the provision of improved dwellings with open spaces”. It was just the beginning of the Rowntrees’ impact on Britain beyond the factory.

The community stood in stark opposition to the abject poverty of the working classes living in York’s slums, which saw entire families crammed into single rooms, drinking from contaminated water sources and dying from preventable diseases.

By contrast, each home in New Earswick had a garden boasting fruit trees, and managers and employees of Rowntree lived side-by-side, with rental costs adjusted to the wages of the tenants. Rowntree also opened the community to non-employee residents in York.

This small community became one of Britain’s first ever examples of a model “garden” village, developed by planner Raymond Unwin and architect Barry Parker, who would go on to help develop Letchworth and Welwyn Garden City.

Even today, says Bridget, “architectural historians come from all over the world - quite literally - to look at the model village”.

York also benefited from the Rowntrees opening a public library in the city centre, from Rowntree Park - gifted as a memorial to the factory’s fallen in WWI - and perhaps most significantly of all, from the adult schools which the family helped to set up and run.

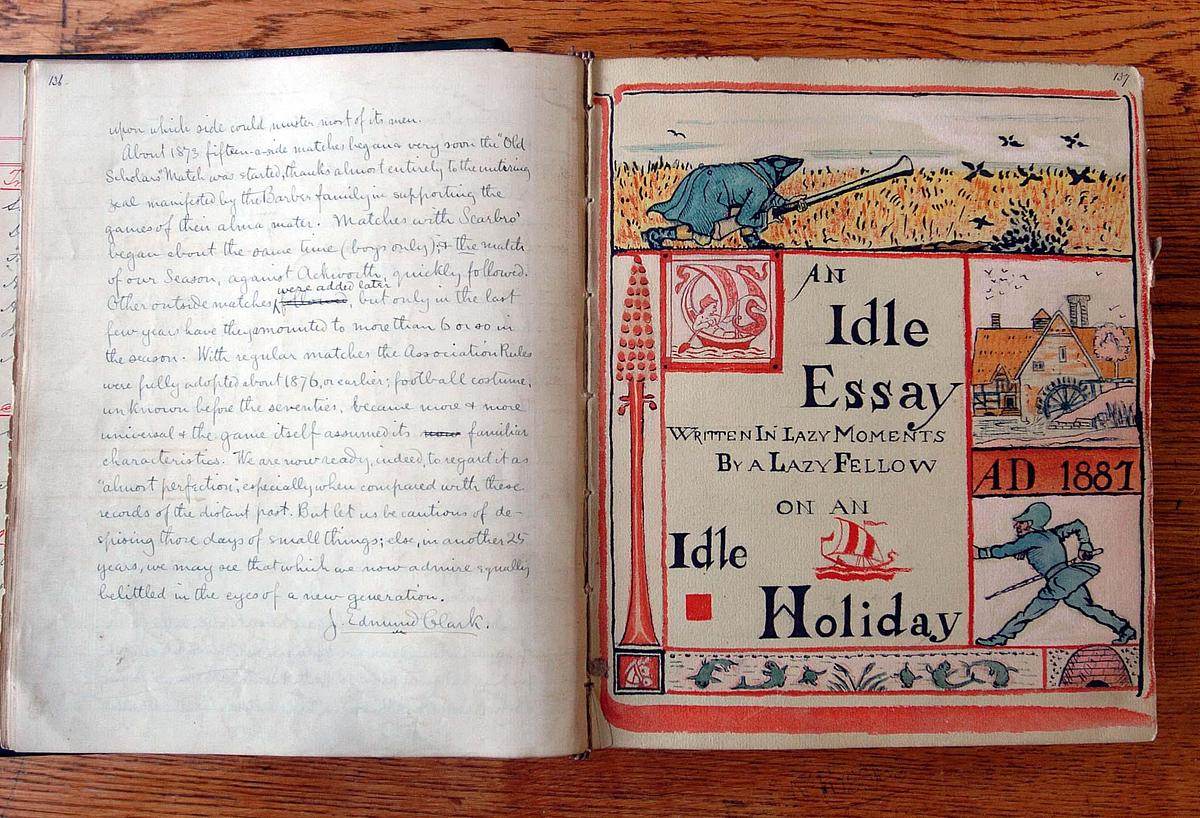

One in five men and one in three women were illiterate in mid-Victorian York. In response, Joseph Rowntree Senior (Joseph Rowntree’s father) and other leading Quakers set up the first adult school in the 1840s.

Successive Rowntrees were all involved with teaching at the adult schools, which were part religious, part educational.

Between 1902 and 1906 the membership of York’s four schools grew from 729 to 2,373, and out of them grew a social club, an allotments society and savings banks - making them one of the few institutions in York to offer such leisure activities to the working classes at the time.

Britain beyond the factory

‘The Einstein of the Welfare State’

Seebohm’s teaching in York’s adult schools brought him into regular contact with the working classes and their daily plight in a society where the odds were stacked against them.

His contact with the poor of York led him to conduct a study into poverty in the city in 1901 titled ‘Poverty: A Study of Town Life’.

This report was not just revolutionary in terms of its content but for its new style of dispassionate scientific analysis, which moved away from Dickensian calls to empathy for the poor to using real-life cases and available figures to paint a factual and complete picture of the scale of poverty.

Using interviews to collect the income and expenditure of working-class households, Seebohm proved that 27.8 per cent of people in the city were living below the poverty line.

Furthermore, he showed that poverty was a cycle, that it was caused by low incomes not spending habits, and most crucially, that being poor was not the fault of the poor themselves.

It was this latter point that made the Rowntrees’ work on poverty especially radical. Politicians and the public had for decades placed blame at the door of the impoverished for their own poverty.

Where leading public figures and communities did pay attention, philanthropic efforts focused only on what Joseph Rowntree called the “superficial” manifestations of the problem.

"It is much easier to obtain funds for famine-stricken people in India than to originate and carry through a searching inquiry into the causes of the recurrence of these famines,” he said. “The soup kitchen in York never has difficulty in obtaining adequate financial aid, but an inquiry into the extent and causes of poverty in the city would enlist little support."

Fulfilling his father's wish, Seebohm’s report had a profound national impact, steering the conversation towards the fact that poverty had underlying structural causes that could be remedied by the government.

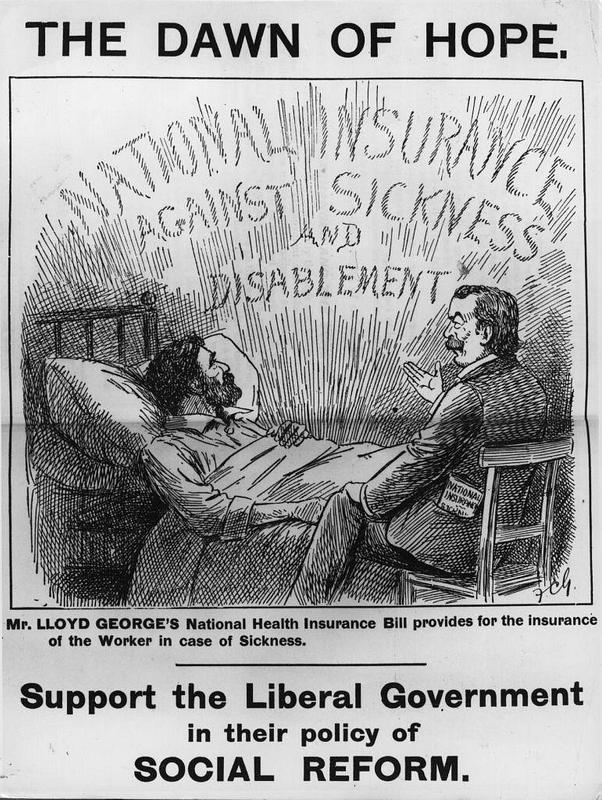

Future Prime Minister Winston Churchill admitted that the book had “fairly made my hair stand on end”, and Seebohm later became an advisor to Prime Minister David Lloyd George off the back of his forward-thinking study.

His contributions to the creation of the NHS and the welfare state through further studies and campaigning even saw him dubbed “the Einstein of the Welfare State” later in life.

Taking advantage of his influence in the political sphere, Seebohm also strongly advised Lloyd George to introduce a minimum living wage for all employees nationwide.

He believed that every man should have a basic wage that allowed him to “marry, live in a decent house and provide the necessities of physical efficiency for a normal family”, adding that businesses who claimed themselves unable to afford it should pay themselves less while making the business more efficient, calling low wages a “false economy”.

In 1904 Joseph Rowntree gave away half of his entire wealth to fund three trusts, the Joseph Rowntree Village Trust (JRVT), the Joseph Rowntree Social Services Trust (JRSST) and the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust (JRCT) - the former to manage New Earswick and housing projects, and the latter two to effect social reform.

Though Joseph Rowntree expected his trusts to close within 30 years of his death, the three have now become a well-endowed four and continue to support a multitude of causes, from press freedom to eradicating poverty.

21st century perspective

'They dared to take a long view of things'

Of course, not every aspect of the Rowntrees’ employment practices was so forward-thinking.

The company’s paternalism was pervasive, from supervisors monitoring bad behaviour in factories to superiors preventing workers from attending York races.

While those who recall working in the post-war factory recall largely happy memories, the moral judgements and paternalism of the company, says Bridget Morris, frequently crop up as negatives.

Having said this, Bridget believes there are still vital lessons to be learned today from the Rowntrees’ approach to social justice: “They dared to take a long view of things and not just find a quick-fix solution...you hear people talk about the ‘root cause’ of problems, that was a phrase he [Joseph Rowntree] actually came up with.”

The Rowntrees’ continuing influence, she says, is “phenomenal”.

Yet while York boasts city centre statues of George Hudson and Emperor Constantine, no such honour has been awarded to Joseph or Seebohm as of yet. Few outside of York and Yorkshire are aware of the extraordinary influence the family had, and continue to have on shaping a fairer society in Britain.

In part, says Bridget, this is down to the Rowntrees’ modesty, and their unique, unshowy style of philanthropy which left little physical legacy of their work:

“In Hull for example you have the Ferens art gallery - one of many art galleries given to cities by rich philanthropists in the Victorian era. Joseph Rowntree didn’t do that, he didn’t give anything physical… he laid down money into the trusts which were about addressing the root causes of social evil.”

The Rowntrees, unlike some other philanthropists of the era, were not just content with bettering the lives of their employees, or even just the lives of those in York. They were committed to making society better for everyone.

It’s for this reason that Bridget believes the Rowntree Society, dedicated to preserving the legacy and heritage of the Rowntree family, needs to exist. Separate to the work of the trusts, she says it is the Rowntree Society’s job to “hold a mirror up to the past” to show how the family dealt with problems still prevalent in society today.

With thousands of working families in poverty, homelessness soaring, dodgy landlords rife and zero-hour contracts making life precarious for many, this “mirror” is a relevant reminder that solving these problems is not out of our hands.

Joseph Rowntree once identified the enemy of human welfare as “selfish and unscrupulous wealth”. Himself a wealthy man, he and his family after him were true to their word, distributing their fortune and demonstrating in the process that it’s not just feasible, more efficient or common sense to look after society at all levels, but the morally right thing to do.

Starting from a modest shop on York’s Pavement, the Rowntrees’ greatest success was, then, perhaps not their still wildly popular confectionary, but the less tangible impression they made, and continue to make on bettering British society.

.jpg)

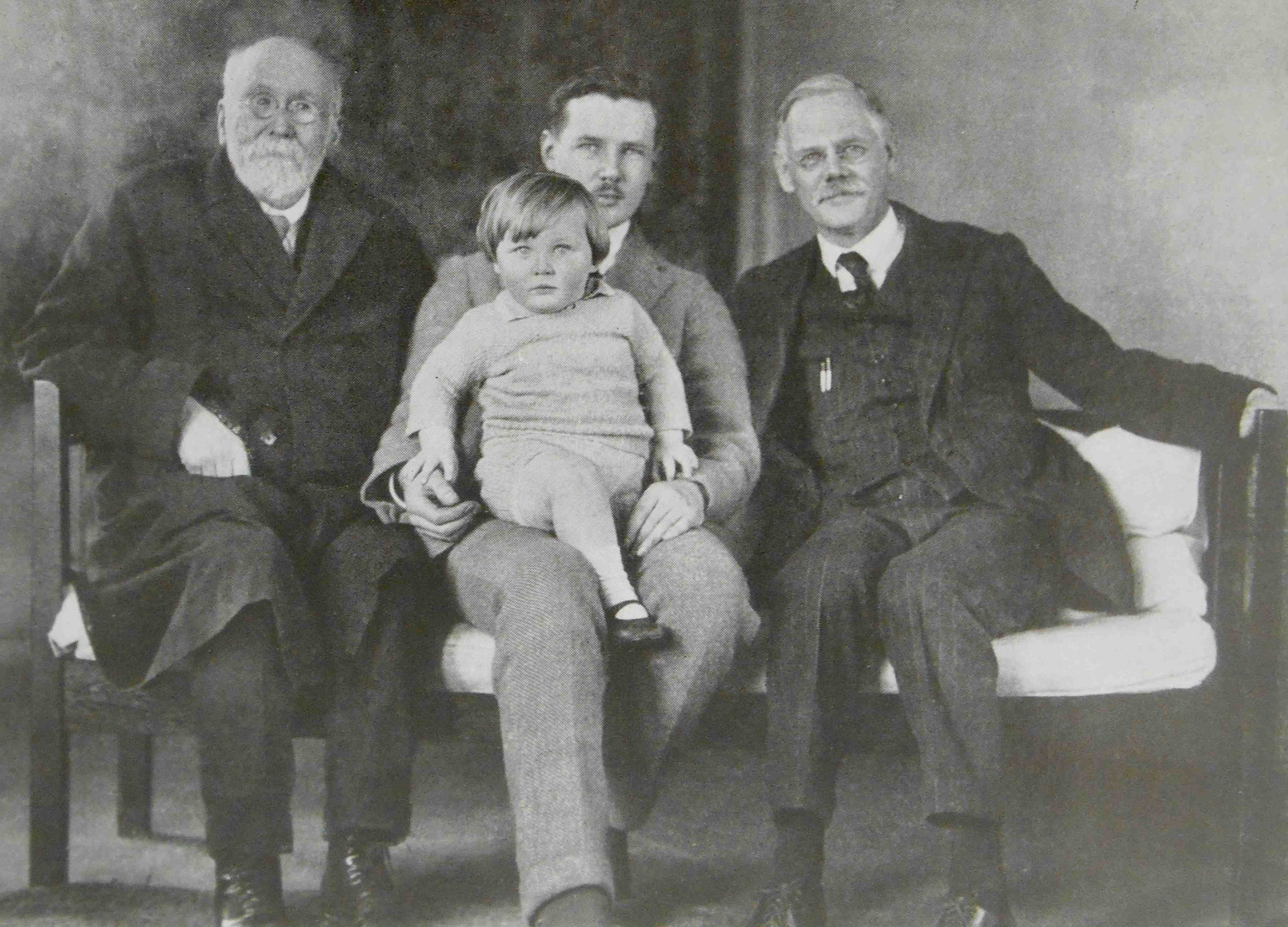

_Joseph,__Arnold_and_Seebohm_Rowntree.jpeg)