In the UK, suicide is the biggest killer of men under the age of 50, a deeply alarming statistic but one which Super League, in partnership with several leading charities, is hoping to eventually help eradicate.

The issue was crystallised in the sport following the tragic death of former Leeds Rhinos, Wigan Warriors, Bradford Bulls and Great Britain hooker Terry Newton who took his own life in 2010 at the age of just 31.

The following year the State of Mind charity was started with the aim of improving the mental health, wellbeing and working life of rugby league players and communities.

Each season, Super League has dedicated a round of games to the cause and with other charities - Rugby League Cares, Movember and Community Integrated - all joining forces to help raise awareness.

Under the banner of Tackle the Tough Stuff, the sport highlighted the most pressing issues in men’s mental health as games were played last weekend in a Wellbeing Round.

In doing so, several high-profile Super League players have shared their personal stories – from struggling with depression and anxiety to dealing with body image and sexuality.

Here six individuals tell their stories including Castleford Tigers and England scrum-half Luke Gale, Leeds Rhinos hooker Brad Dwyer and Huddersfield Giants prop Matty English.

However, it is worth remembering it is only a snapshot; given how widespread the mental health issue is, there could just as easily have been many of their team-mates or other players from all dozen Super League clubs with similar tales to tell.

In the UK an average of 84 men take their lives each week, something Super League’s biggest ever mental and physical health campaign hopes to start driving down while helping improve the wellbeing of all.

Huddersfield Giants prop Matty English, 21, was captain of the club’s Under 19s side when team-mate Ronan Costello, 17, was injured in a tackle against Salford Red Devils in 2016. After being airlifted to hospital for emergency brain surgery, Costello tragically died three days later.

I was a bit older than Ronan - 18 at the time - but in the same Academy side and was unfortunately there that day it happened. I was stood just yards away.

It’s a day I would love to forget. But it’s a day I never will.

There was a lot of emotion. Weirdly, I think it brought us all very close - all the boys that were there that day - and there is definitely a team spirit where, I guess, we are all trying to live on in Ronan’s spirit.

It’s something that I always take into every game with me; Ronan was a player that never held back and always had a dig for the boys and that’s what I always try and do.

It left us all very very shocked and upset obviously but it’s something I felt I didn’t deal with very well at all.

I felt being the captain of that side and being one of the senior boys that I almost had a responsibility to look after the younger boys in the squad.

Because of that, I felt that I didn't grieve properly for Ronan.

It was only a few years down the line that I realised I wasn’t right. Well, I think I always knew. But then I admitted it.

I spoke to my mum and dad about it and told them I was struggling.

My mum begged me to get in touch with Steve Hardisty, our player welfare manager at Giants, who was outstanding from start to finish.

He put me onto a counsellor and I was so sceptical about that to start with. It felt stupid to me; how could talking to a stranger help me at all?

But after 10 minutes of the first session I felt so at ease talking to her and that really did help me. I guess that’s why I wanted to do this now - talking ahead of Super League’s Wellbeing round - as talking about the tough stuff in rugby league is massive.

We play a sport where we’re supposed to be tough - we’re supposed to run into brick walls for a living - and I feel like the message is we’re still all human beings and we still all have real emotions.

With Ronan’s death, we all handled it very differently but it’s so taboo. Obviously we all wear the same wristband and we all knew exactly what happened but we never really spoke about the hard conversation.

We always spoke about what a legend he was and how much he loved the game but we never asked each other ‘How are you doing?’

I wish we had done that and we’d have got through it better together.

We still all get together and it is a special bond that we all have got. We might see each other on a night out or, for example, a couple of months ago I saw someone in the White Rose (Centre) and it’s obviously still that special bond that we all have with each other.

We were all unfortunately there that day. And it’s a friendship we’ll all keep forever.

Obviously, losing a team-mate like that is the last thing you ever expect to happen when you run out on to a pitch. Most of us have all played the game since we were six or seven years old, had a game every single Saturday during the season and then just that one weekend that had to happen to us.

"That was one of the toughest things. I asked it all the time. Why? Why me? Why Ronan? Why did it have to be us? It was a tough time.

I was so shocked when I got there to see the counsellor as she didn’t do that much talking. She just opened a blank canvas for me to just sit for an hour every week and talk about anything. To be honest, for the first couple of times I don’t think we even hardly mentioned Ronan. We just got to know each other. Chit-chatting. Slowly she just put little prompts in there just to get my head ticking away and answering questions in my head that I never thought I would.

It’s so important to talk and to reach out.

Leeds Rhinos hooker Brad Dwyer, 25, is now an ambassador for Birthmark Support Group having - after feeling suicidal - only recently discovered he had never truly dealt with lifelong insecurities about his facial birthmark

Tackling mental health awareness is an issue throughout life and should not just be targeted at rugby league players.

It can affect anyone. I was born with a birthmark before I was a rugby league player.

It’s just I’m fortunate the career I’ve fallen into is doing so well at given me a platform where I can speak about it.

I was a bit naive to my birthmark as a kid. I struggled with it. I struggled with all sorts - the name-calling, the bits of bullying - so there was all those challenges all kids go through.

But mine was just related to my birthmark and sometimes a bit more extreme.

I had these masks, though, of rugby league and sports; I was always good at them and I wasn’t fussed. I impressed in those ways.

I was always on the front foot with humour; I always took the mick before they could take the mick out of me really.

I probably got to the age of 25 - being successful in rugby and having a good personality where you can have a laugh - to then hit rock bottom and break down and realise that I’d never really accepted this problem that is going on with my birthmark. Or accepted that is who I am.

It took me hitting rock bottom to actually start dealing with it and that’s the process I’ve been through on the last year.

I went through a break-up and did what most people do - I went out for a good drink. I woke up with a lot of anxiety which some people do after a drink anyway.

But I knew I wasn’t dealing with things well. Fortunate for me I had Fats (Nigel O’Flaherty-Johnson) as our player welfare manager at Leeds who is a qualified counsellor as well.

I gave him a phone call as I was having thoughts of ending my own life.

It was strange; it wasn’t the fact that I was going to do it - I had no intention of going and doing it - but these thoughts kept popping into my mind and I didn’t know why.

It was the first time I had ever felt like that and I just knew that was a trigger for me and I needed to speak to someone. At that moment, it was nothing to do with the birthmark and I just wasn’t feeling good about myself or dealing with it how I wanted to. But I got speaking to Fats and he was asking me all these questions but I said it’s nothing to do with what’s going on.

Then we realised all this stuff was relating to not dealing with my birthmark and I wasn’t comfortable getting out of my comfort zone… being in a relationship, meeting new people… and it just opened a can of worms really.

I then went through a process of trying to get the birthmark removed. For a second time. But I couldn’t do it because of the career I have; there’s bruising after laser treatment so I wouldn’t be able to play rugby and have that treatment.

So I decided I needed to do something about it and hit it head on. So when I came back from our October break that’s what I did. Nothing to this scale… I was just going to put a picture of it on social media, speak about it and then so everyone knew so I didn’t have to approach someone or a situation where I’d be covering it up with my humour or rugby. I’d be comfortable with myself and accept who I am.

Then Fats got the idea of getting involved with a birthmark charity as well and they’ve been great, too. But speaking in this round as well for Super League has been great. It was all for a selfish reason at first for me to accept who I am and be comfortable but all this feedback I have had has been overwhelming. It’s probably the first piece of happiness my birthmark has ever caused me over the last couple of weeks.

People have been messaging me with their own insecurities - nothing to do with birthmarks but weight, the way they look, etc, things they are struggling with - and it’s made the jump I made really worthwhile.

The big issue was for me to accept it. I can’t change other peoples’ opinions on it. The problem I had was my own. I needed to accept it and that’s why I came out with this process.

I don’t think I will get it removed now, even when I’ve finished playing rugby. You can never say never as I don’t know what state of mind I’ll be in then. But doing this process I’ve now turned it from a negative into a positive and I feel in a unique position now where I have a great platform to speak about it.

I'm getting some great feedback and it’s up to me to speak about it and get it out to everyone.

For 25 years I didn’t have a clue. Looking back, in 2016, I probably was depressed but I didn’t realise that at the time as I had no reason to be.

We were so successful as a team - winning the League Leaders Shield with Warrington and reaching the Grand Final and Challenge Cup final - and my off-field was happy. There was no upset there.

But for some reason I was unhappy and I just didn’t understand it. But that breakdown - and then talking to someone about it - made me realise.

Hull KR’s Australian prop Mitch Garbutt, 30, has a qualification in counselling and talks about the importance of player welfare managers in helping rugby league players at all levels cope with all sorts of issues.

A friend of mine Hayden Butler was in the Under 20s at Melbourne Storm when I was just moving down there as a player full-time.

Unfortunately he took his own life. He was a great fella and a person you would never expect to do anything like that but he did. He was someone who you would just never think had anything wrong and it’s heartbreaking to think about.

You think about people like that all the time. You never knew. There was no way anyone could have ever known what he was going through.

Maybe his parents did or his girlfriend at the time might have but his mates definitely didn’t.

He was always the life of the party and that’s a common theme especially in sport; rugby league is full of working-class men who like having a good time and it’s so disappointing that things can end like this.

That’s why this Tackle The Tough Stuff campaign and Wellbeing Round is so important.

The aim is that, in an ideal world, no one would ever feel that (suicide) is the answer. Although to them they think it’s the only answer it isn’t.

Rugby league has taken great strides in breaking it down and making it known it’s okay to talk about your feelings and no one will feel any less of you.

It’s not as taboo as it once was; people know it’s an issue.

I think Stevie Ward at Leeds Rhinos did a great job a few years ago bringing out Mantality magazine.

I know when he first launched it he copped a bit of stick from the boys which is what rugby league boys do; they’re like brothers in that sense.

But Stevie has done a brilliant job and really driven it home. Super League has to give him a lot of credit for getting rugby league and the mental health side of it out there to the wider public.

Hopefully we’re past the stage of it being a subject people are scared to talk about.

Counselling is something I’m really interested in. I started studying in 2015 and got my Level 3 counselling while I was at Rhinos.

I’ve also got an Australian qualification in Level 4 career development and welfare.

During my career, I’ve had some really good welfare managers who I think have done a good job and it is such an important role.

I got to professional rugby league the long way. I played two years in the local league and didn’t debut until I was 23. It’s been a long journey. I’ve got there eventually but it hasn’t always been easy.

In Australia, a lot of clubs have multiple player welfare managers as they have just got such a big playing rosta; there’s 35 NRL players, 40-odd Under 20s, then Under 18s, Under 16s... so it just has to be done.

There’s too much heartbreak for kids not making it, not achieving their dreams, who think they will just be alright by themselves. But it’s been proven that’s not the case.

The good player welfare managers make you realise that rugby league is not the be all and end all of life. Not everyone is lucky enough to play at the top level and definitely not everyone is lucky enough to earn good money.

There’s a lot of players, especially in Super League, who could probably earn more digging holes and laying bricks.

Not everyone is lucky enough to get a house paid off and things like that from playing this sport. I always say we do the most physical work and get the least amount of pay from all the big sports. But that’s what you sign up for.

I just think the younger kids have to focus on things away from rugby league and you end up performing better.

Hopefully I’ll move into it (player welfare) when I retire. I’ve had a few chats at clubs where I’ve been and it might be an option.

I’m a qualified electrician so if I had to do that I could do that but I’m definitely passionate about the player welfare side of the game.

I did my four-year apprenticeship as an electrician and was lucky enough to get the offer to go to Melbourne for two years and that was probably the turning point for me. I went down there into a great system full of great people that probably made me know what it takes to be a professional athlete. I’ll be forever grateful for that. I didn't play as many games as I would have liked but have really fond memories of becoming a better person while I was there at the Storm.

During his time as Batley Bulldogs captain, Keegan Hirst had contemplated suicide before - in 2015 - revealing to his family and friends he was gay, becoming only the second British professional rugby league player to come out. Now playing for Wakefield Trinity, the 31-year-old prop admits it was the best decision he could have made and urges others to speak up about any issues.

Suicide is the biggest killer of men under 50 and it’s because people don’t share their issues and talk about their troubles, for whatever reason.

There is a lot of stigma around men and mental health and not being able to talk and having to tough it out.

I think it’s important seeing people you might look up to - professional rugby players who are physically tough and go out and do a tough job - being able to talk about our insecurities and the things that bother us, us being depressed or struggling to get up to do a job we love doing and it’s not an alien concept for people out there.

If we can talk about it hopefully it will give people the confidence and the courage to be able to do that in their own lives.

I came out four years ago. Am I surprised no other rugby league players have done so since? I don’t know how many more gay rugby league players there are, if any, but coming out is such an individual thing; you have to accept who you are.

That was difficult for me to do for many years. There may be gay rugby league players who don’t want to go public about it and that’s also okay.

You have got to be okay with other people knowing about it. I’m not surprised and it is a really difficult one.

By the law of averages there probably are more (gay rugby league players) and has to be some. You can sit and deliberate it but I remember when I came out saying I don’t want to go on a crusade and be a role model…

And then - after all the messages and letters of support I got - I realised if I didn’t that would be wrong.

But that’s me. Other people might not be like that. It’s something I am proud to say I do, but I can understand why people wouldn’t want to and maybe that puts people off - having to talk about it all the time.

But we know in our game they’d be welcomed with open arms.

Back then, I had to (come out) for the sake of my physical health, my mental health, my relationships with myself and my kids - they are infinitely better than they ever were before I came out. That’s something I am really happy about. And it seems like a million years ago now.

Castleford Tigers and England scrum-half Luke Gale, 31, has still not played yet this year having ruptured his Achilles tendon in pre-season training. The former Man of Steel also missed most of the last campaign with a fractured kneecap.

The last 18 months have been horrendous, if I’m honest. Injury-wise I’ve been on the sidelines more than actual playing.

It’s easy to get down. When I did my Achilles in January, I had maybe three or four weeks off. And my motivation was terrible.

But it was going back into training that got me back. The support of my team-mates is what really helped.

As soon as you’re back around the lads, back training, something changed for me.

As daft as it seems, I think Macca (team-mate Paul McShane) absolutely hammered me.

I can’t remember exactly what he said but I remember thinking ‘I’ve come in, first day back, knowing I’m going to miss at least six months of the season and they have all taking the Mick out of me. And that’s great!’

It helped me massively. It’s my life and it’s great that rugby league has that sense of community. That’s the beauty of our sport - all being one big family.

It’s great what the Tackle The Tough Stuff campaign is doing now building up to this Super League Wellbeing Round.

Mental health is massive, not just in sport but in life in general, and rugby league is helping get rid of the stigma of not being able to talk. It is okay to talk.

We’re kind of big macho players but we know more than ever how important it is to show our emotions, talk about things and tackle any issues head on.

I’ve gone through a lot of things during my rugby league career. Losing my mum to cancer back in 2013 I can remember having two or three days off then and just thinking I’d rather be back around my mates.

I was at Bradford Bulls at the time and every single one of the lads came to the funeral which was a massive support mechanism for me. It was my coping mechanism as well; that’s how I dealt with it all.

I remember my first day going back in and saying ‘Lads, don’t treat me any differently, I’m back in.’

That’s what got me through it. Rugby league’s great for things like that. There’s a great sense of support.

We knew it was terminal but you almost think it will never happen until it actually does and nothing can get you ready for that moment.

But Franny Cummins was coach at Bradford at the time and he was outstanding along with all the lads.

It was the day of the game as well when it happened so I didn’t play. But a few days later I just wanted to get back in. That might not work for everyone.

You never get over it and the one way to do help was being around the lads.

But whatever you do, it is always important to talk to someone.

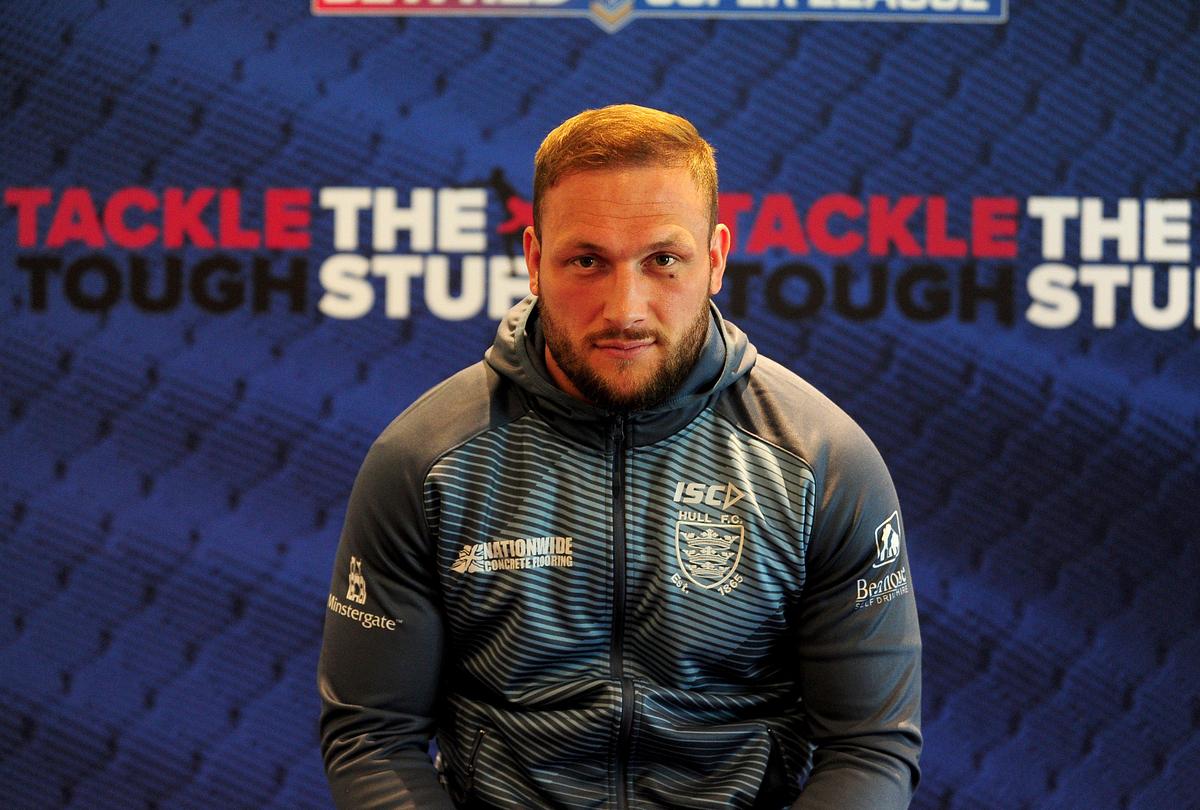

Hull FC centre Josh Griffin, 29, speaks about playing at Magic Weekend in 2015 just days after the death of his father and also fund-raising for former team-mate Jansin Turgut who was left fighting for his life after falling from Ibiza Airport car park.

It was the worst experience of my life losing dad all of a sudden. I’d spoken to him on the Friday night when we (Salford) played Warrington.

He had a few health problems but he was fine and we were expecting him back the next day. I lived with my mum and dad at the time.

But the next morning he had a heart attack, went into hospital and passed away on the Tuesday.

My dad didn’t have the best lifestyle, bless him, especially the last couple of years.

He had some real bad health problems but he was a big, strong thing; we got used to him and it turned out he had had two heart attacks. The doctors said the first one should have killed him and would have killed most people.

I remember getting the phone call at three in the morning. We were in the hospital for four days and the last message I had was the nurse saying he was doing really well and I think he’ll get through this. We left thinking he would be alright but got home and got that phone call which saw us rush back but we got told that he had passed away.

We talk about the ‘rugby league family’ but obviously I’ve got my family within that as my brothers George and Darrell both play. I was fortunate they were there and we were all playing for the same club as well so we helped each other through it.

We played just four days after he passed. It was Magic Weekend. Me and my brothers left our family on the Friday afternoon to go up and play in Newcastle on the Saturday. At the time, we said we wanted to do that as it was the first time the three of us had ever all played together.

We wanted to do that for him but looking back now it was probably too soon.

I’d not slept properly all week, my emotions were all over but getting back into the swing of things did help. I was back in training two days later and it helped getting some fresh air and running around a bit. Rugby helped me escape for a bit but when I stepped away from that that’s when it hurt more and I struggled more.

I spoke to Gaz Carvell, our Player Welfare Manager at the time, and he put me in touch with someone who could help. Speaking definitely helped, I needed to get things off my chest.

Men are meant to be these big tough creatures but bottling it up is the worst thing you can do. I felt like a huge weight had been lifted off my shoulders when I spoke about it.

Everyone knows about Jansin’s accident. I go see him a lot in the hospital; he’s coming around and doing better every day and the rugby league family has been massive in helping there.

We’ve raised more than £25,000 so far and there’s still other things in the pipeline. Seventeen grand went into getting Jansin home (from Spain) and we’re raising as much as we can but obviously this Wellbeing round has come at a good time to remind people of mental health and raising awareness, not just in our sport but for men in any sport and life in general.

Men need to speak more about their emotions. Jansin’s a typical bloke. He gave off this tough persona and didn’t really speak about his emotions. He’s had his issues off the field. We still don’t know what happened. But he’s going to need people around him now and that’s where this support is going to come in more.