On 25th December 1944, Mrs Goodyear of Bramley Avenue, Sheffield, sat down to Christmas dinner as she’d done every year before - but with one key difference.

Away fighting on anti-submarine boats in the war, Mrs Goodyear’s son was conspicuously absent from the table.

In his place was Josef Grudel, a German prisoner of war (POW) from the very country her son was in battle against.

It’s a story that sounds unbelievable, perhaps even a one-off, and yet all over Yorkshire - and indeed the country - ordinary people followed suit and welcomed POWs into their homes en-masse for Christmas in 1946, with the wounds of war still fresh in memory.

It wasn’t just Christmases either.

In Yorkshire - the region with the highest number of POW camps during WWII - unlikely relationships had been forged between locals and “enemy” prisoners before the fighting had even ended.

Many of these relationships tell a touching tale of Yorkshire hospitality. Yet with the passage of time and the fuddling of records in the chaotic post-war period, the stories of those thousands of POWs who made Yorkshire their temporary home - and the many who made it their permanent one - are beginning to fade from living memory.

Right across the county, from quiet villages to bustling cities, former prisoner of war camps today lie beneath shopping centres, car parks and decades of overgrown shrubbery - burying a fascinating chapter of Yorkshire’s history that’s all-too-often forgotten.

Prisoner of war camps in Yorkshire

Prisoner of war camps in WWII Britain began with just two sites in Lancashire - a number that would spiral to over 600 by 1948, as repatriation efforts dragged on for several years after the war’s end.

Thanks to the loss and destruction of records after the war - an accident that Eden Camp WWII museum archivist Jonny Pye says had “no malicious intent...it was more a case of ‘what are we going to need these for’” - the exact number of camps in Britain, let alone Yorkshire, is unknown. As late as 2019, ruins like those excavated at Lodge Moor camp in Sheffield are still being uncovered.

By several estimates, however, Yorkshire housed the highest number of prisoner of war camps in England, with officials often requisitioning existing buildings like racecourses (Doncaster, York) and large homes (Scriven Hall, Harrogate) for the purpose of housing POWs.

Yorkshire's POW camps, mapped:

Not all locations have been included. Locations are approximate and not exact.

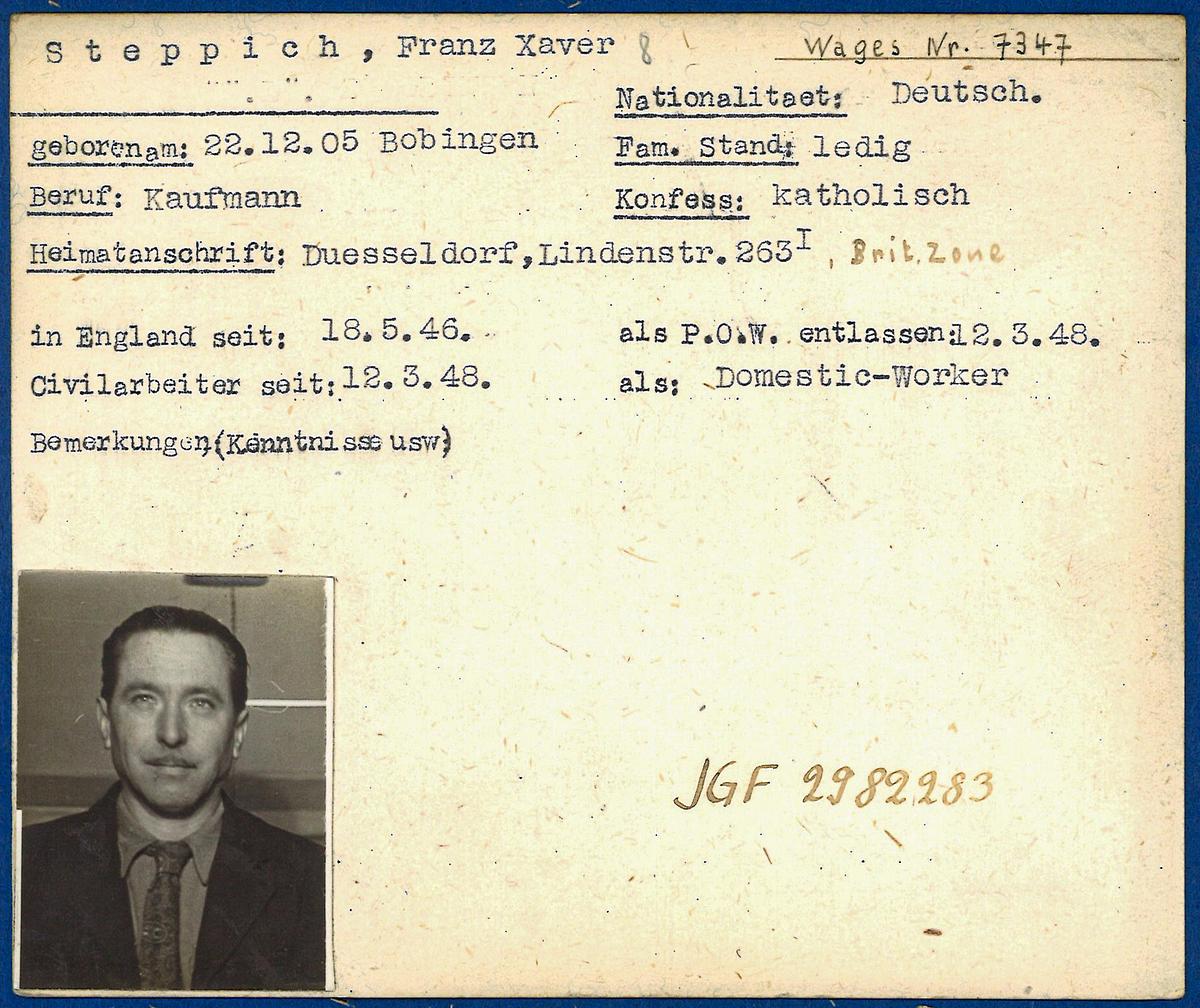

POWs brought to the UK were largely of Italian and German origin, and their entry to the UK began as early as 1939.

German POWS were sorted into three different categories upon arrival with a corresponding uniform patch that indicated their loyalty to the Nazi regime. “Black” Nazis were the most hardline, while grey was middle-ground, and white was for those with no particular loyalty to the party.

Though many of the “black” Nazis were shuffled off to camps in the north - including Lodge Moor - a great number of Yorkshire’s POW camps held “low-risk” men with less or no loyalty to the Nazi party. It was these men whom the British government hoped could be re-educated in the values of democracy.

Life in the camps

'Yorkshire people were the nicest from all over England'

Though life as a POW in Britain was not easy, and certainly varied greatly from camp to camp, treatment of prisoners was considered generally good. POWs were even given the same food rations as British servicemen - higher than those of British civilians.

‘Re-education’ programmes were implemented by the government early on as a means to ‘de-Nazify’ prisoners - a scheme that was more successful in some places than others. Teaching materials included using the POW camp newspaper - Die Wochenpost - to print German news bulletins side-by-side with Allied ones.

Some prisoners, accustomed to strict press control in their own country, were shocked that British papers had the liberty to criticise their government. Others ripped these bulletins up to use as toilet paper.

Unlike in many other camps across the world, POWs in Britain were compensated for labour (often agricultural work) with pay, though this was often in the form of “camp money”, paper and plastic facsimiles that negated the possibility of POWs using sterling to pay their way to escape.

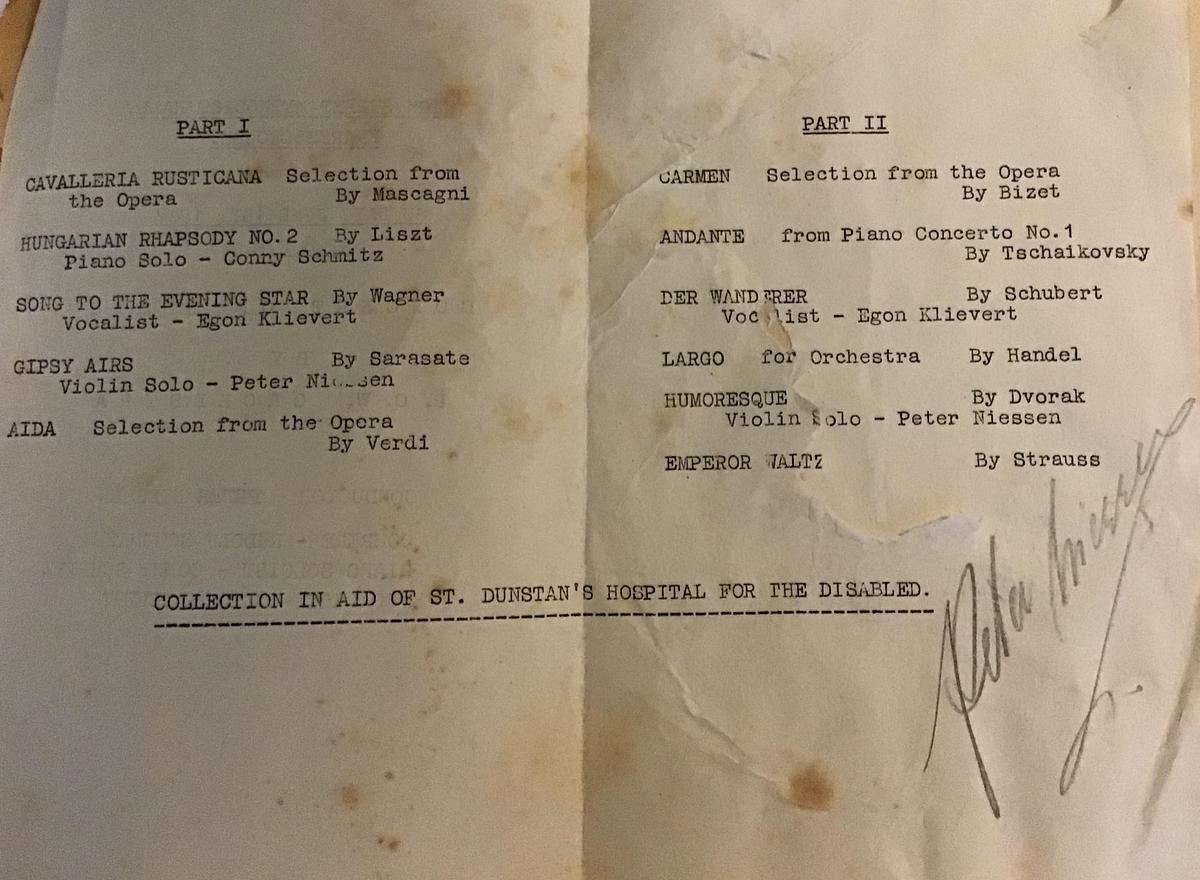

Many camps provided POWs with other means to pass the time too. Butcher Hill camp in Leeds was reported to have a well-stocked library of around 2,000 volumes, while Eden Camp in the North Yorkshire market town of Malton had its own chapel and held weekly Literary Club meetings as well as lessons in mathematics.

One POW, Hans Baldes, who was interned at Eden Camp, even returned to the site - now a WWII museum - in 1999, telling staff:

“I always thought Eden camp was the best POW camp I was in, and found Yorkshire farmers and people were the nicest from all over England.”

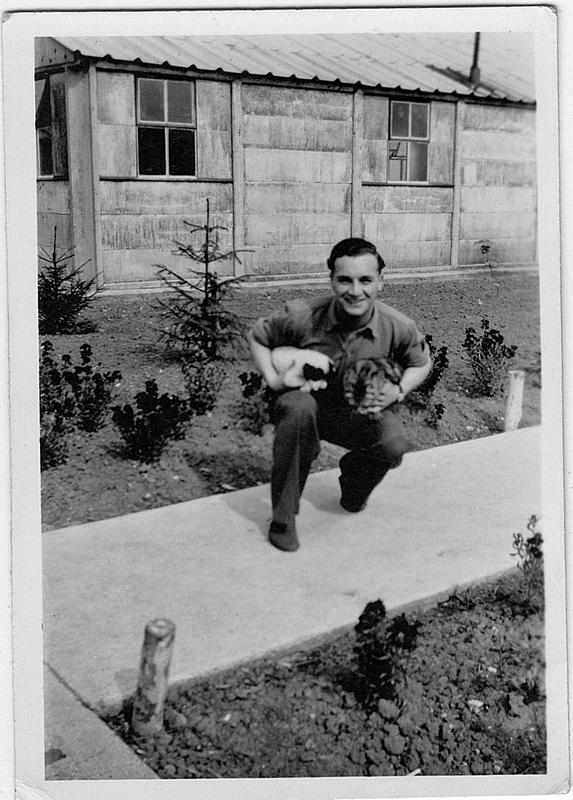

It seems a surprising statement from someone who was, by all intents and purposes, a prisoner of the British state. Yet this sentiment has often been echoed by prisoners interned in less hardline camps, where internment itself was even fairly lax.

As the years went on, and particularly after the war’s end, prisoners were granted increasing freedom to roam in the local communities around the camps.

St James' Church in Leeds saw POWs attend Sunday services to bellow out hymns alongside the congregation, while John Hogg of Scriven recalls attending musical concerts given by POWs in the old Methodist church on Knaresborough High Street. Steve Race of Leeds has childhood memories of seeing POWs do vital work clearing Scott Hall Road of ice and snow during the winter of 1947.

Love Stories

'They’d stand up and click their heels when the ladies came into the room - Yorkshire girls weren’t used to it!'

Once POWs began mingling in their local communities, the inevitable happened for many: they fell in love.

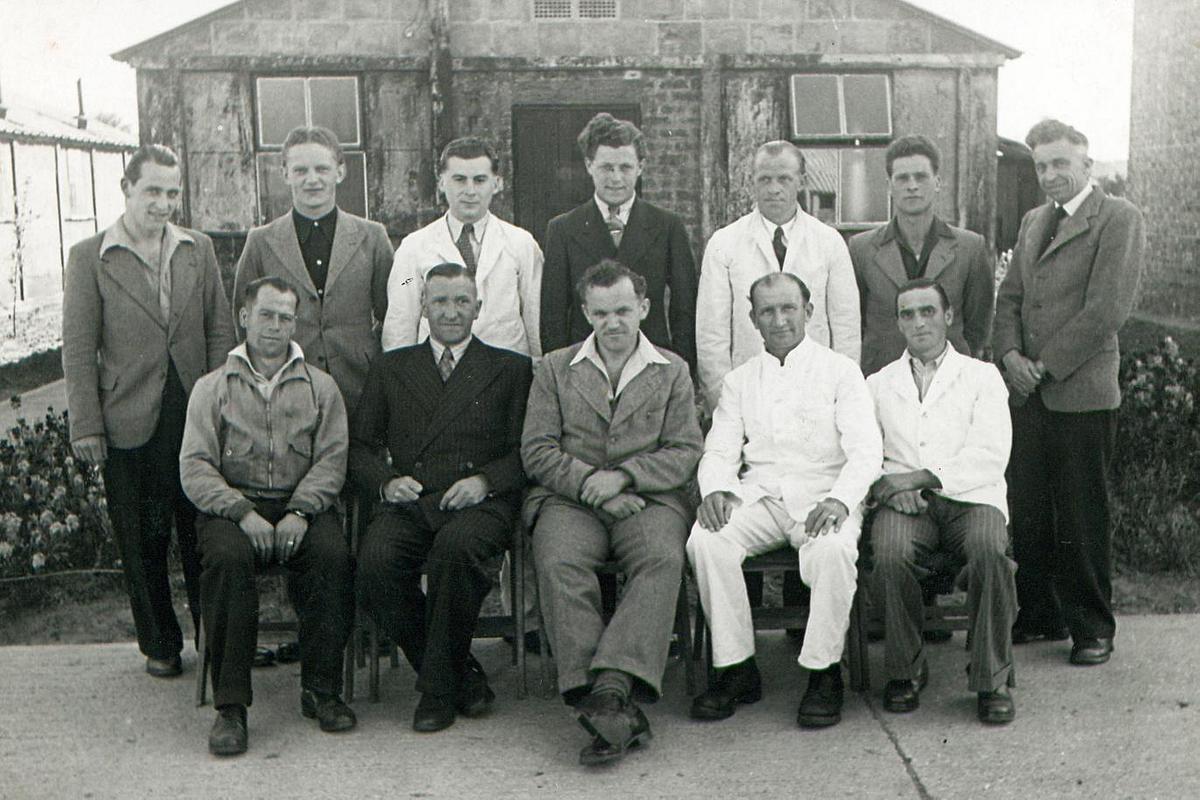

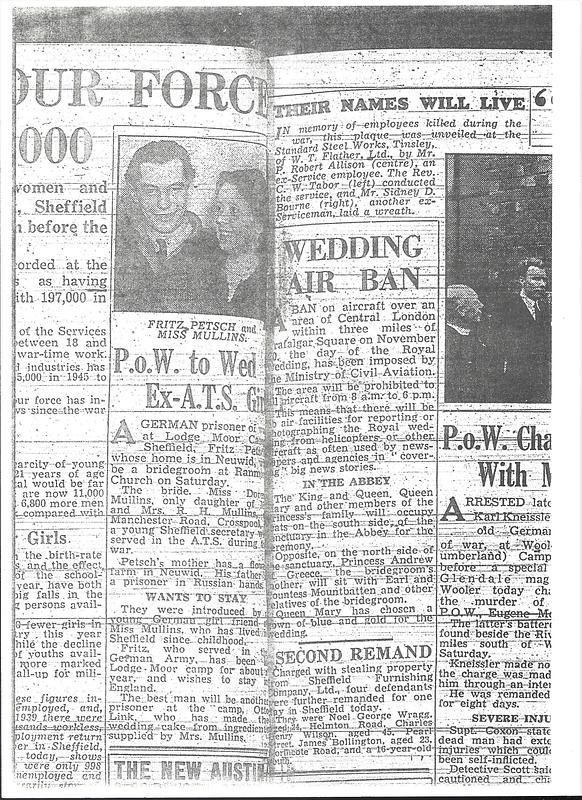

Fritz Petsch was one such POW. Falling into enemy hands at the tender age of 16, he spent most of his war being carted around different POW camps before finally landing in Redmires Camp, Sheffield.

Slow repatriation efforts meant Fritz remained for a couple of years at Redmires after the war’s end. Though an aggravating situation to find himself in, it was thanks to the tardiness of the British Government that Friedrich met his wife, Doreen.

As his daughter, Denise Vernon explains:

“When the war was over they [the government] encouraged local people to invite prisoners to their homes. My grandparents lived in Sheffield, and invited my father and another prisoner to their house for tea on a Sunday afternoon - that’s how it all started.”

It was here that Doreen laid eyes on her father for the first time, and, Denise explains, it was the POWs’ good manners that struck her mother the most:

“I remember her telling me how really polite they were, they’d stand up and click their heels when the ladies came into the room, they had really good manners...Yorkshire girls weren’t used to it!”

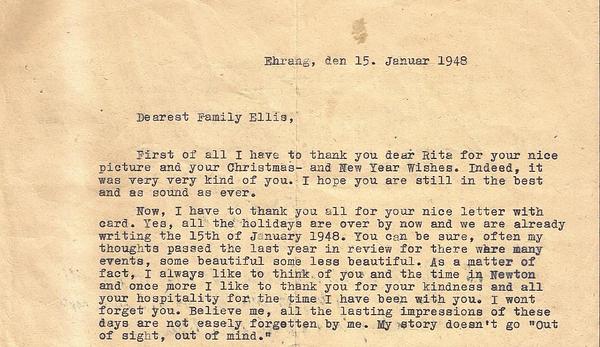

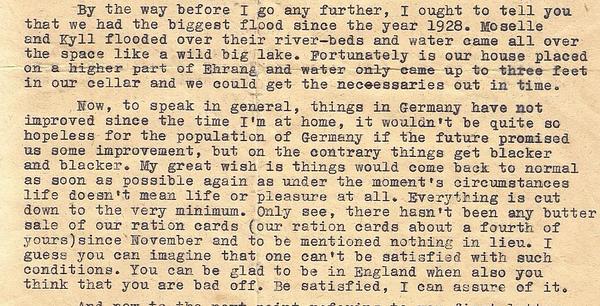

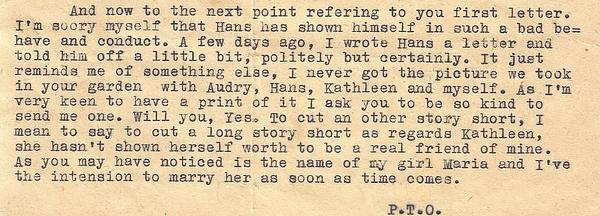

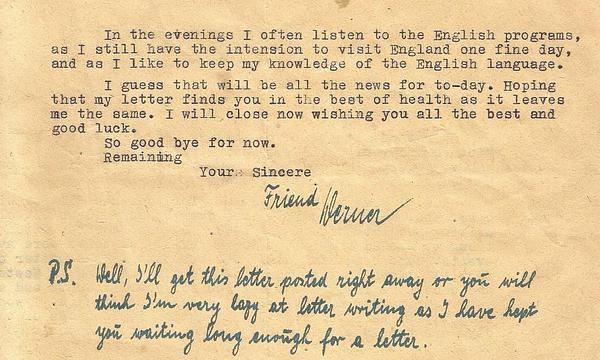

Marrying a POW didn’t come easy, however. In 1947 - the year that Denise’s parents eventually got married - British politicians were debating the 12-month imprisonment sentence handed out to POW Werner Wetter for his “association” with a British girl.

When Denise’s own parents wished to marry in 1947, “the English commander of the camp researched my father’s background in Germany... my grandparents were given that information before the wedding.”

Most startlingly of all, Doreen was considered a state “enemy alien” by merit of her marriage to Fritz, and was required, Denise says, “to report to the police every week”.

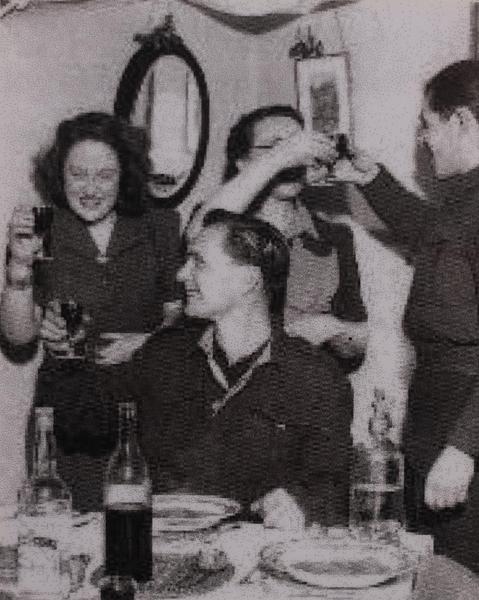

At the wedding, says Denise, her father has since joked that he “made sure everyone had a drink in hand at the wedding reception”. The fact he worked in the officers mess at the camp facilitated this.

In defiance of the societal - and state - barriers impinged on them, Doreen and Fritz went on to have Denise, and though her parents later separated, she says it was “a true love story at the time”, and far from unusual: when state restrictions were eventually lifted on marriage between German POWs and British women, it’s estimated that more than 700 marriages immediately took place, with many more to follow.

Unlikely friendships

'You get to know them and you realise they’re just people'

Naturally, things were not so rosy for all the POWs held in Britain - not just for those in more hard-line camps, but also for those interned after the war's end.

Proving useful as a labour force when so many British men had been killed abroad, the government were reluctant to repatriate German POWs immediately, a source of frustration and anger to many who were desperate to return home.

However, while the government was dilly-dallying in parliament, it was local people who strove to make the lives of POWs as comfortable as possible while they were still interned.

Where there certainly had been animosity towards Germans upon their arrival as POWs, and not everyone ended up warming to them, many local people did eventually become sympathetic towards the prisoners - especially after the end of hostilities.

As Jonny Pye puts it: “Anecdotally, people in the area did get on with them. It’s a classic story really, at first you look at ‘them’ as the enemy then you get to know them and you realise they’re just people.”

A government call for citizens to invite POWs into their homes for Christmas 1946 was taken up enthusiastically by many across the country - leading, in many cases, to further visits and lifelong friendships.

After Mrs Goodyear hosted Josef Grudel and another POW in their Sheffield home for Christmas, her granddaughter Bet Brooke explains that they “became lifelong friends until they passed away”.

“We used to go to Germany and spend our holidays with them from me being very young until I was 11 or so,” she adds.

POWs were also known for crafting toys for local children, and in one touching case, POWs in Knaresborough in 1948 hosted a party in the Knaresborough Methodist hall for 100 local children as a thanks for the warm hospitality they’d received in the area.

When the time for repatriation came, in fact, thousands of German POWs no longer wanted to return home. A government scheme aiming to retain 16,000 Germans for (paid) agricultural labour had to adjust its target when in excess of 25,000 requested to stay.

Reasons for these requests to stay varied. Many East Germans’ hometowns had fallen under Soviet rule, while others simply no longer had family in the country.

One of the most common reasons, however, says Jonny Pye, was that “they found a girl”, and many of those POWs who stayed in Yorkshire made it their home for the remainder of their lives.

Their legacy

'Anti-German feeling was very strong when I was growing up'

It’s estimated that at one time, POWs were doing around a quarter of all Britain’s agricultural and construction work, much of this including rebuilding bombed parts of the country.

During the harsh winter of 1946/7, they stood side-by-side with Allied troops in helping to reopen essential roads and railway links.

It’s key labour that is often - perhaps wilfully or not - lost from the historical narrative of post-war Britain.

In fact, Denise believes that the flush of hospitality shown by some towards ordinary German POWs immediately after the war has since waned into anti-German sentiment that still lingers on in Britain today:

''Until the age of 19 I kept my German name secret because anti-German feeling was very strong when I was growing up and my father was never mentioned at home.

Brexit gave me the incentive to apply for the German passport that I have always been entitled to and I now have dual English and German nationality.''

Aside from WWII museum Eden Camp, the invisibility of these camps today is perhaps one of the reasons this chapter of history is so often passed over - though small traces do remain.

The ornamental fountain that stands where Stoorwood camp (Cottingham) once was, for instance, can be credited to POWs, while surviving concrete huts at the former Scriven camp are reportedly scrawled with faint German writing.

Christine Hearn’s mother, of Knaresborough, was taught German by a POW. Christine says she “still remember[s] the lullaby she sang to me in German”.

Others recall having toys crafted for them by POWs, or regular house visits on a weekend that led to lifelong friendships and penpals.

Those without such memories would be forgiven for assuming that animosity towards Britain’s German “guests” would have been rife in the years during and immediately following the war.

These POWs were, after all, the supposed “enemy” and were using up Britain’s rations and resources at a time of extreme scarcity.

Yet in a similar vein to the brief Christmas armistice of WWI, the forgotten stories of how POWs and locals found warmth, friendship and love with one another are a touching testament to how many Yorkshire folk once put aside prejudice, choosing hospitality and kindness even in the face of the ‘enemy’.

In today’s divisive and turbulent age, it’s a timely reminder from history to look past prejudice and hatred even when it might not be the easiest choice.

_(1).JPG)

_(1).JPG)