All in defence of the realm

On a crisp and clear day, life is continuing much as normal in Howden. The shops and cafes are as busy as ever, but nearby, in the shadow of the famous Minster, a group of people are gathering to remember one of the most extraordinary events ever seen in the town. Eighty-five years ago, Howden earned a place in aviation history when a luxury passenger airship, almost as high as the church tower, took off from the outskirts of the town for its very first flight.

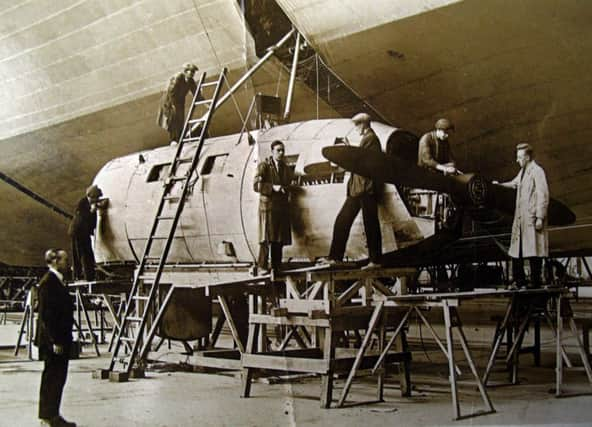

The R100, designed by a team led by Sir Barnes Wallis, had six Rolls Royce engines and could carry 100 passengers and 38 crew members. Many local people were employed to build the gigantic cigar-shaped flying machine, which would soon cruise to Canada and back at a maximum speed of 81mph. Waitresses dressed in smart black and white uniforms served those on board.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdSir Barnes’ daughter, Dr Mary Stopes-Roe, was a toddler when the airship was launched in 1929 and watched as it emerged from its shed, pulled by hundreds of soldiers, before being released into the air for the first time. She was with the group that gathered recently to remember that feat of aviation engineering, and unveil a commemorative trail to mark its construction.

A series of plaques have been placed in the ground along a stretch of pavement more than 600ft long – the exact length of the R100. Each one gives details about the gigantic machine and the amazing men who took the plans from the drawing board and into the air.

While Sir Barnes Wallis is best-known as the man who invented the bouncing bomb, the airship is just one hint that the engineer, scientist and inventor had a career of much greater breadth and depth.

“He was not at all the man of war that he seems to have been remembered as,” says Mary. “I don’t think he thought the bouncing bomb was his major achievement. He was actually much prouder of the aircraft that came later. What he wanted to do more than anything was teach and inspire the young to make, create and invent.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdDespite those sentiments, even people who do not know his name will probably know about Sir Barnes’ bouncing bombs, which in the Second World War were used in a raid on German dams. The aim was to flood – and so destroy – factories in the Ruhr that were involved in the war effort, but the cost on both sides turned out to be much greater.

Fifty-three of the 133 British airmen involved in the operation were killed and another three were taken prisoner. On the ground about 1,300 people died, including hundreds of Ukrainian prisoners of war. Many factories, power plants and bridges were damaged or destroyed, although the mission’s success has been questioned. Perhaps its greatest achievement was that it boosted morale back home in Britain.

Sir Barnes, who died in 1979 aged 92, was devastated by the deaths of so many British airmen in the raid and according to Mary, he never got over it. “After that he said he would never again risk a man’s life,” she adds. Sir Barnes felt so bad about the deaths that he donated the £10,000 government award he received for inventing the bouncing bomb to education.

As the war continued he went on to develop other explosive devices. The adapted Avro Lancaster was able to deploy his Tallboy bomb, which sank the German battleship Tirpitz. He also invented the 12-ton Grand Slam, the so-called earthquake bomb.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAnd, according to his daughter, he would do it all again. “He would have said that it was his duty to defend his own country against evil people. If you can’t take up arms against people who attack you, you are a pretty weak person. If he were alive now and thought we were in danger, he would rise up and do what was necessary.”

It can be argued that Sir Barnes’ bomb-related work also, ultimately, saved lives. Mary said he thought that the Second World War could be shortened if critical resources were attacked in Germany.

“The whole point of his thinking was to hit targets that produced the weapons the enemy was using,” says Mary. “He was never ever into scatter bombing, just precision bombing, which is an extremely skilled craft. He never ever made any attempt to destroy civilian locations.”

Mary, who has a PhD and is a retired historian, psychologist and the author of two books, wants people to know more about what her father did apart from his work with bombs. She attends many events to highlight his inventions. That is partly what brought her back to Howden, her birthplace and the town where the Barnes Wallis Memorial Trust holds an annual meeting.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdKnighted in 1968, Sir Barnes certainly had fingers in many pies. By 1945 he held more than 100 patents and his work on aircraft included the first use of geodesic design in engineering. This is a type of construction that helps flying machines withstand greater stresses than regular airframes. It was used in airships and also in the development of bomber planes, including the Wellesley and Wellington. The design allowed damaged planes in the Second World War to limp home and land safely, saving countless lives.

After the war, Sir Barnes continued his research, but in more benign areas of life, investigating supersonic travel and a bewildering range of other, diverse projects. He worked on producing lighter callipers for polio victims, radio telescopes and nuclear submarines and developed good relations with the people he worked with.

“He loved the workmen, he loved everything about them,” says Mary. “The workplace of yesteryear was a far more dangerous place then it is today. There is one story concerning the building of the R100 about a Scottish rigger (a man employed to work on the framework of the airship) named Sandy who almost fell whilst working high up. My father said to him: ‘Sandy, what have you been doing?’ Sandy replied: ‘I’m alright, nothing wrong with me, but it’s my teeth’. His false teeth had fallen out and crashed onto the concrete floor 140ft below and broken.”

Sir Barnes Wallis might have made his name working with airships, aeroplanes and falling bombs, but his first love was in fact the sea. He initially worked as a ship engineer, based in Cowes on the Isle of Wight, before the First World War. Mary said he wrote to his mother weekly describing how he enjoyed his work with destroyer engines. She added: “He had his own sailing dinghy and lots of friends. They camped and did a lot of sport. He had no idea of going into the air. It was complete chance that drew him in that direction.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThat chance was a friend and colleague in Cowes, who left to work in the airship business. Sir Barnes followed him. Mary said: “It always surprised me, because he did not write about things like flying across the Channel or the Wright brothers. He was much more interested in the water, but he went up in the air and never came down again.”

Despite his extraordinary workload and success over the years, his daughter said Sir Barnes was a family man who insisted his greatest achievement was his 20 grandchildren. When his sister-in-law and her husband were killed in a wartime air raid, he and his wife adopted the couple’s two children, to add to their own four offspring.

Sir Barnes was also a man who believed in doing something for the wider community. He uncovered an old Tudor structure at his local church in Surrey, was secretary of the parish council, and gave time and money to educational advancement and charity.

Mary said her father was always keen to share his intellect, especially with the young. “If you asked him anything he would tell you. He would describe it, write it down on the back of an envelope, show you the formula and draw a diagram. He had no idea of secrecy. His values were hard work, structure, duty and organisation. There was nothing floppy about him, nothing vague. I can remember him saying that any fool can invent something, but someone has to make it work.”