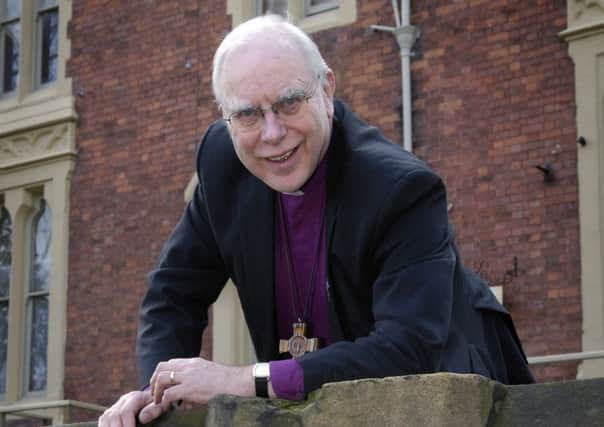

A new chapter in life as Bishop John bids farewell

No matter who and where you are in life, there are always firsts.

And for the Rt Rev John Packer, Bishop of Ripon and Leeds, there are a couple of belters coming up. First, he is being made redundant and, second, he is buying a house for the first time ever. At the age of 67, that’s not bad.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdTo clarify, it is officially retirement, but the bishop cheerfully admits it is redundancy in a way since he is going earlier than the mandatory 70 years of age because his patch is disappearing. There will be no more bishops of Ripon and Leeds.

Two other bishops are meeting the same fate as the Church of England massively restructures the area. The big new job will be as Bishop of Leeds and it has already been advertised, calling for “an experienced, inspiring leader with a heart for the people”.

Bishop John is completely in favour of the change: “Our boundaries do not make sense.and the changes will help us to focus our ministry more effectively,” he says.

As for his own future, the new house is a Victorian end-of-terrace and he and wife Barbara are excited about it. They have the keys now and are in the process of doing it up.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIn the past they have been able to advise their three adult children on many things but never on the machinations of home buying, but now they know all about it.

Currently Bishop John, a kindly and cheerful man, lives in Headingley, Leeds, in an official residence. From there he is responsible for 140 paid clergy and the same number of non-paid and retired clergy. He says his job as a bishop is all to do with relationships.

“There are important managerial elements to it in that you are seeking to get the best out of people. With paid clergy, sometimes you have to challenge them. If a vicar is spending all his time making his church beautiful you have to say ‘shouldn’t you get out more?’ And vice versa if the church is being neglected, but it is mainly about encouraging people.”

As for how he got to where he is now, it has been a life of contrasts.Bishop John, originally from Bolton, studied history at Oxford. He considered life as a social worker but in the end chose the Church and his first job as a parish vicar was in South Yorkshire, a world away from the dreaming spires.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdBack then, in the depths of the 1970s, the region was known as the Socialist Republic of South Yorkshire, and it was full of miners and everything that went with their way of life – from working men’s clubs to pigeon fanciers’ clubs to pit bands. I remember it for I lived there too and, as I speak to Bishop John, I realise that, in one of those strange quirks of life, we have met before.

His parish of Wath-upon-Dearne was my patch as a young reporter and I nervously imposed upon him for parish news. I was there often for the bus fare to the vicarage was very cheap – there were advantages to living in a hotbed of left-wing politics.

Just up the road from the vicarage, incidentally, was Wath Comprehensive School where a 16-year-old pupil called William Hague granted me a composed interview in the school corridor after a precocious speech at the Tory Party Conference. It was all happening in Wath in the 70s.

Bishop John says: “I think I was most fulfilled as a parish priest, in Wath, and then on the Manor Estate in Sheffield. Many clergy find the first parish where they have been vicar is very important, it is where they learn how to be a vicar.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“You learn that people will react to you in very different ways, and some will be angry or sad. You also learn there is lots of pettiness, like in any other group, and people have very different expectations of the church.”

Bishop John was in South Yorkshire when the event that defined the era took place – the 1984 miners’ strike. It lasted a year and its heartland was South Yorkshire, but the strike proved to be a catalyst that changed the politics, economy and thinking of the entire country. He helped support both striking miners and those who were shunned by their colleagues for returning to work before it had officially ended.

“I was thrown into a very different way of life,” he says, adding his memory of that time has been stirred recently as he has seen food banks set up to help those who cannot afford to feed themselves. Helping the vulnerable is Bishop John’s constant concern and, as a member of the House of Lords since 2006, he speaks on issues to do with poverty and disadvantage. He has recently challenged the rules on both welfare reform and on immigration, particularly on how they will affect children and the disabled.

But as he prepares to leave at the end of January, Bishop John has words of praise for the city of Leeds and its council leaders.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“Leeds has responded well to the challenges of austerity and it has been good to work with the council on its response to increasing need within the city.

“The city is very open to the voluntary sector and to faith communities and it is only if we work together that we will be able to provide support for those who have been damaged.”

After Wath and the Manor Estate in Sheffield, his own career took him to the beauty of the West Coast of Cumbria.

“I was asked to go there by my archdeacon who said it would not be as different from the inner city as I thought .”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHe became a member of the General Synod, elected by other clergy to represent them, and then an assistant bishop before taking his present and final job in 2000.

So, does a vicar rise to become a bishop because he is ambitious? Bishop John doesn’t think it is like that: “People become ordained to be parish priests and then some of us are called on by the Church to take on other roles.

“I went where I was asked to go, in the days when people did what they were told to. We have less instinctive respect now, and I think that is a good thing. Also, I was on the General Synod and that does get you noticed.”

Though he is leaving his post, he will always have the title of bishop and is optimistic about the future of the church.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“It is true that the number of people attending week by week has declined but the number of people coming to church for special reasons has remained the same. The moments when communities want to draw together are as strong as ever, maybe even stronger.”

What has changed is that the Church is more flexible now and there are different forms of church. Currently, under the umbrella title of Fresh Expressions, many types of church are being created, says Bishop John.

There is, for instance, Messy Church (for families), Cafe Church (bringing people together over a coffee) and Network Church (online groups who meet occasionally).

It is entirely possible he will be called on to take occasional services in his new neighbourhood – the house he and Barbara, a maths teacher, have bought is in Whitley Bay, Tyneside, to be near their daughter Catherine, who is a vicar in Newcastle, and their son Tim, who works in Durham.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdTheir son Richard works for a train company down south. His interest in transport began in South Yorkshire with those cheap bus fares, says Bishop John.

One of the things he would like to do in retirement is volunteer with the National Trust.

“My diocese might use me to cover vacancies and emergencies but I am looking forward to some freedom and flexibility,” he says.

Looking back on his stay in the city, Bishop John thinks the period of the 7/7 bombings in 2005 when four suicide bombers, three of them from Leeds, killed 52 people in London and injured many others, was both the best and worst of times.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“I am proud that there was not a backlash in Leeds. I was able to go meet with Muslim leaders and pray with them and be part of saying Leeds is a place where people of different backgrounds want to live together in harmony. And the fact is that we do have good community relations in Leeds.

“I have mixed feelings about leaving. I don’t want to leave but after 13 years it is probably time for someone else to come in. It is the right time.”

jayne.dawson@ypn.co.uk