Bradford College lecturer: War criminals murdered my father in Bosnia

Three days after Samir Dizdarevic turned 18, the soldiers came for his father. The next morning, he and his family made the horrendous discovery of his parent’s barely-recognisable body – along with the mutilated corpses of three of their neighbours – which had been left on a road on the outskirts of their village in Bosnia.

“Mum came home screaming,” he recalls of the events of August 1992. “She said, ‘Samir, you haven’t got a dad anymore’. I insisted on going to see. I was 18, it was my dad and I wanted to see him for the last time.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“When we turned up, it was like a scene from a horror movie. You are there standing over these dead bodies. They had all been badly tortured, dad’s face had been completely smashed in. I could only recognise him because he was bald.”

Samir’s father Mesud and his neighbours were among the thousands of Bosnian Muslims killed in ethnic cleansing during the Balkans conflict in the 1990s.

Now, 27 years on from his father’s murder – and after giving evidence against one of his killers just months ago – Dizdarevic is speaking for the first time in public about his family’s traumatic story, as well as his extraordinary personal journey from arriving in Yorkshire as a refugee unable to speak English to becoming a respected lecturer at Bradford College.

Now 44 and a father-of-three himself, Dizdarevic is meeting with The Yorkshire Post after recently opening up about his harrowing experiences with college staff and students for Holocaust Memorial Day, which this year had the theme of ‘Torn From Home’.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdDizdarevic finds an empty classroom in Bradford College’s £50m David Hockney Building away from the hustle and bustle of passing students to explain the long and harrowing story that began when he was a college student himself in Bosnia and has resulted in him building a career in education and a life in West Yorkshire, more than 1,000 miles from his home village.

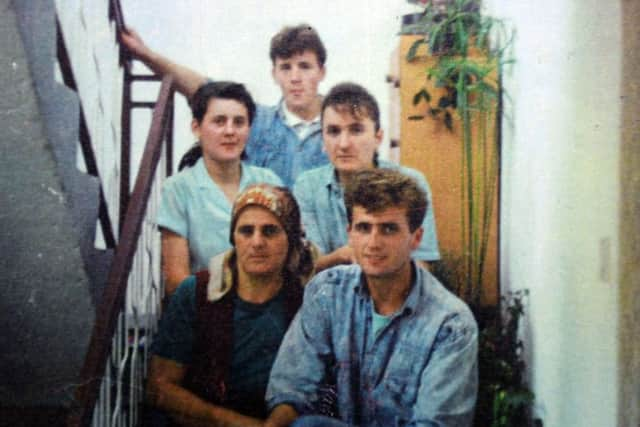

Samir was 17 and living with his parents and siblings in the village of Kamicak in north-west Bosnia when the Bosnian War started in April 1992. It was one of several interlinked conflicts connected to the break-up of Yugoslavia that would ultimately result in the deaths of around 140,000 people.

Dizdarevic says he grew up enjoying a comfortable family life after his father had spent much of his working life as a builder in Germany where numerous projects were under way to repair towns and cities ruined in World War II. But the escalating tensions in the region began to have a direct effect on his life after the Croatian War of Independence began in 1991 as some of his teachers went off to the frontlines to fight.

After Bosnia and Herzegovina declared independence from Yugoslavia following a referendum in February 1992, Bosnian Serbs led by the now convicted war criminal Radovan Karadžić and supported by the Serbian Government and the Yugoslav People’s Army mobilised forces to secure what they saw as Serb territory. War soon spread across the country, accompanied by ethnic cleansing. As the frontline came closer to their home, Samir says the family felt powerless.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“Mum had a sister that lived in Slovenia. At some point, I suggested to Dad we should be sending my sisters and mum out. He flatly refused and said no. But a few months later, he said ‘I should have listened to Samir’.”

He says his father’s decision to stay came from not wanting to leave the family life he had worked hard to build in the village. By the time Mesud changed his mind, it was too late.

“You could hear bombs going off further afield but you thought, it is not going to happen to me, surely it is going to stop at some point. But once they had taken over the communications like the radio and television stations, then you realise we are trapped in here now.

“Electricity was cut off but we desperately searched for batteries to listen to the news to see when help was coming. We were expecting Nato and the West to intervene. The Yugoslav army was one of the biggest in Europe and there was no way we could fight them.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“They were clearing town by town and eventually came to our area. Refugees had started arriving in our villages before and they told the stories of what was going on. At that point, we knew we were in big, big trouble.”

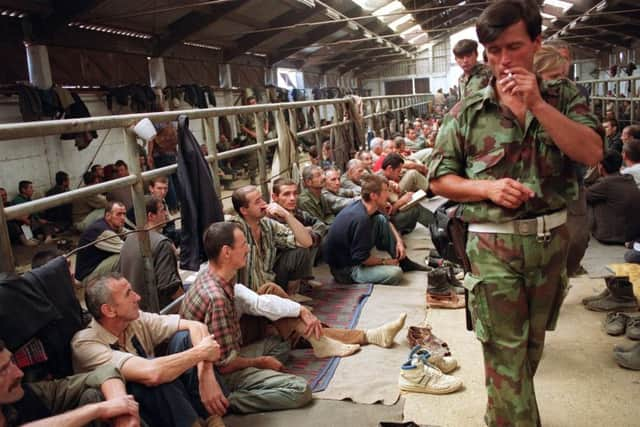

By the time the Serbians arrived in Kamičak, two of Dizdarevic’s uncles who lived nearby had already been sent to the Manjaca concentration camp where thousands of Bosnian Muslim men were imprisoned. The International Court of Justice subsequently heard evidence of the ‘inhuman’ conditions at the camp, with beatings, torture and rapes of prisoners, as well as the discovery of a mass grave of 540 people believed to have been kept there.

But Samir says he was saved from being sent to the camp by one Serbian when soldiers arrived in his village. “They lined us up, they were splitting us up telling people to go to the left or the right. When my turn came, a soldier said kneel down and go with the ladies and children. He saved me from going to a concentration camp and may have saved my life. My dad didn’t go either because he was classed as disabled.”

Dizdarevic says he later discovered one of his friends had died while being transported to the camp after suffocating in the back of an overcrowded truck taking prisoners there.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThose who remained in his village were initially allowed to go about their lives in peace in exchange for providing supplies to the Serbian soldiers when they demanded them. He says his family were able to survive as they had some farm animals, while his mother had built up a store of supplies.

But things changed dramatically after a few months.

“We were living there in fear but nobody from the hamlet was killed,” he says. “They were not touching us.

“Three days past my 18th birthday, in the evening somebody started knocking on our door calling, ‘Come out’. There was this massive soldier holding a Kalashnikov asking for the man of the house. They said to mum, we need your husband.

“But they were saying somebody’s else name, actually asking for a neighbour. Dad said, ‘I’m Mesud’. But they still said, ‘We need you to come with us’. Dad put a shirt on and they went down the road. They came back past again five minutes later with my dad and a neighbour and at least three to four soldiers.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“They had picked a time when it was difficult to see what was going on. At that point we were really nervous because we had heard the stories where people had been taken for questioning. But the whole night we were expecting Dad to come back.”

He says it took some time to process his father’s death. “In these situations, you actually don’t fully realise what has happened and you become a bit more selfish and fear for your own life. You are thinking, how am I going to survive?”

Samir says he believes the Serbians had decided to round up ‘influential’ villagers so they would have more control over those left behind – but says he is still unsure whether they meant to come for his father or whether he was unlucky. “My dad was there at the wrong time and they were asking for a neighbour. I still don’t know how they stumbled to our door.”

The family, fearing for their lives, left their home and slept in the nearby ruins of an old castle in tents. Eventually the Serbians offered the villagers a choice – sign over all their possessions in return for being transported to the border.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“At that point, it was nothing. Dad had worked in Germany, built a house, had a nice family and a comfortable life and didn’t want to be separated from that. But by then, we were just fearing for our lives.”

They were transported to the Slovenian border in trucks ‘like cattle’. The family eventually ended up in Croatia in the relative safety of Zagreb, but his older brother was made to stay and fight for the Bosnian army.

“We stayed in Croatia for a year living mainly on humanitarian aid delivered by the Red Cross and other charities from the UK.”

When his uncles were freed from Manjaca concentration camp, they were offered asylum in Britain – with one moving to London and the other to Bradford. The rest of the family were eventually granted asylum to join them and were sent to a refugee centre in Dewsbury. They arrived in the UK on Bonfire Night in 1993 as explosions from fireworks filled the air.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“I was thinking, my God, what is my destiny?,” Dizdarevic says with a smile. “But we were so glad we were free of everything we had seen. Even now, we reflect on how much help and support we received from the British government and the local British community.”

Dizdarevic started on an English for Speakers of Other Languages course at Bradford College in 1994. He went on to do a computing degree at the then-Leeds Metropolitan University, graduating in 2000 and initially working for PC World as an IT technician. But he became a part-time lecturer at Bradford College in 2003 and in 2007 was offered a full-time post.

Samir says it had been emotional to speak to staff and students about his family’s experiences, as well as events such as the Srebrenica massacre in July 1995 when 8,000 Bosnian Muslim men and boys were killed. But he had several reasons for opening up about the past.

“It is very rare when I talk about it that I don’t end up crying, the emotions take over. But I feel an obligation to talk about it. My dad was only 47 when he died and I am nearly his age as I’m 44 now. I want to spread the truth about events in Bosnia and motivate my students to go to university and do well in their careers by saying ‘this is how I got to where I am now after coming to Britain empty-handed’.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“Barely anybody knew the full story. I was stopped by a number of colleagues saying ‘we never knew this had happened’ and how courageous I was to share something so private.”

His brother was wounded in the war but wasn’t allowed asylum to the UK after the conflict ended and now lives in Switzerland. However, the rest of the family have made lives for themselves in Yorkshire – with his mum also in Bradford and sisters living in Huddersfield and York.

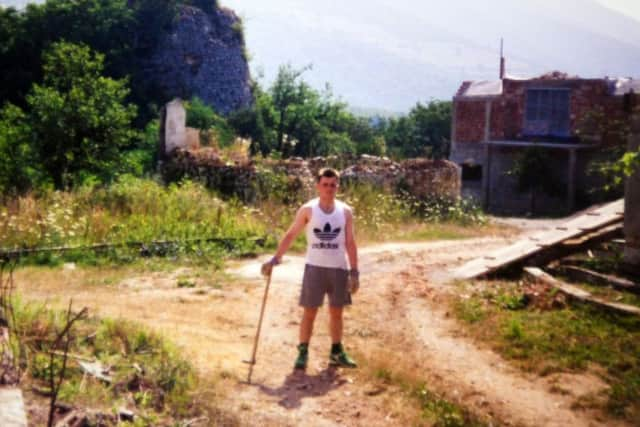

But he goes back to Bosnia every summer with his wife and three boys – driving through Germany as a reminder of his father to get there on each occasion.

“It reminds me of my dad seeing some of the buildings he might have worked on. Going back is a feeling you can’t describe. Even though I have spent most of my life in Britain, when I’m driving, I don’t want to stop. My life is now counting down to the summer holidays and after the holiday.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdLast September, he went back again – this time to give evidence against one of the men involved in the death of his father. In December, former teacher Bosko Devic was sentenced to ten years in jail for crimes against humanity for his involvement in the murders with three other soldiers.

A report on the case on the Balkan Investigative Reporting Network, which specialises in reporting on war crime trials, said the killings had taken place as part of a wider “systematic attack” on the civilian population in the local municipality.

“Presiding judge Saban Maksumic said the deaths of Serb policemen, which preceded the Bosniaks’ murders and were cited by the defence as a catalyst for them, did contribute to tensions and was a kind of trigger, but the violence against Bosniaks that followed went beyond an isolated event,” the report said.

“When deciding on the sentence, the court said it took into account the brutality of the attack and the mutilation of the bodies. It also took into account the fact that the defendant did not commit the crime independently, but did not express any disagreement with the killings either.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdSamir says of the conviction: “You are getting some closure, even though ten years doesn’t seem like justice to me. But at least you can say, he is a war criminal.”

But he says he particularly struggled to deal with the fact that Devic was once a teacher as he is now.

“What sort of message was he spreading to his pupils and students? This is why we need to speak out. The events in Bosnia should serve as a reminder that unless we work very hard on uniting communities together, this is what can happen. I’m not saying it will happen here but it happened not so long ago in Bosnia.

“When I came to Britain, what I found was this huge lack of true information. Probably nobody in Britain knew there were these people in Bosnia in the heart of Europe suffering so badly. I strongly believe if people knew the extent of the bloodshed and torture, I think they would have forced the Government to have acted sooner and done something about it.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHe says the loss of his father has never left him. “When we were growing up, my dad was working so hard in Germany he missed our childhood. My dad would have loved so much to be here now playing with his grandkids.

“I think we can all learn together from these events and live better and have a better understanding of each other. That is the reason why I want to speak out.”

College’s praise for Samir

Samir has been praised for his powerful talk to staff and students about his experiences for Holocaust Memorial Day.

Lenka Kaur, Inclusion and Diversity Coordinator at Bradford College, says: “Samir approached me after one of our previous events and expressed an interest in sharing his story in the hope that it would help students to understand the journey of others, the impact of prejudice and hate that can end with disastrous consequences, and, how perseverance and resilience can help them to achieve their goals.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“It must have been extremely difficult for Samir to revisit the most horrific time of his life when sharing his story; we are so grateful to him for his strength and openness.

“Having one of their own tutors discuss his relatively recent life experience made it more ‘real’ for students and allowed them to understand these things don’t just happen in other parts of the world, they impact us here as people around us have had these lived experiences.”