Bradford: Grim images of city whose chimneys belched out death

Comparing the city’s pollution levels to the very worst in London, he wrote the following: “If anyone wants to feel how a poor sinner is tormented in purgatory, let him travel to Bradford.”

This was ironic, as the Yorkshire historian Paul Chrystal, points out, since the city’s industrial fortunes had been built on the expertise of his countrymen.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHerr Weerth, whom Engels called the first and most significant poet of the German proletariat, made his home in Bradford for three years and bore witness to those dying around him, writing his findings in Marx’s newspaper, Neue Rheinische Zeitung.

“Bradford was bigger and better than Leeds – one of the great engines of the Industrial Revolution. But it a darker side to it,” says Mr Chrystal, whose book of images from the city’s archive has just been published in partnership with Historic England.

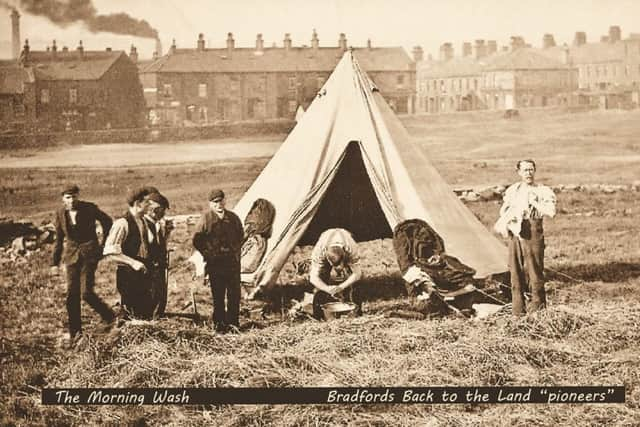

“The incredible pollution was really the worst in the UK, and that was borne out by the infant and adult mortality rates. People tended not live much longer than 25 or 30 years, because of the smoke.”

The industrialist and social reformer Titus Salt, after whom the model village of Saltaire is named, tried to mitigate the effects of the smoke belched out from the mill chimneys by attempting to promote legislation that would make them taller.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“The higher the chimneys, the less the chance of pollution from them infecting the people down on the ground,” says Mr Chrystal.

“But Salt didn’t have much support from his industrial colleagues. All they wanted to do was make money, while the rest of the people literally choked to death.”

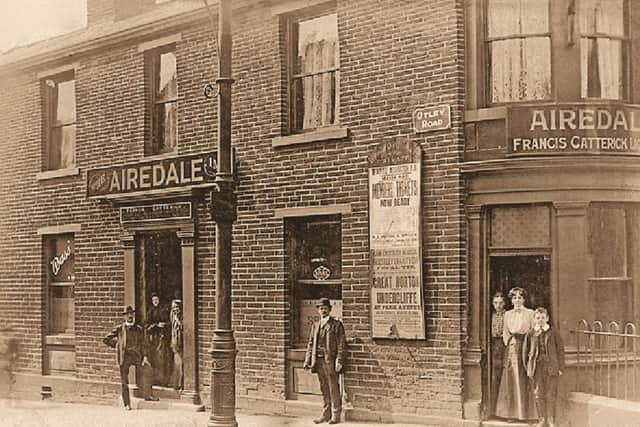

Many of those industrialists had come originally from Germany, where they had gained experience of heavy industry along the Ruhr. But they had moved away from Bradford itself to the leafy suburbs and the countryside.

“They just went into town two or three times a week to shout at people,” Mr Chrystal says.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

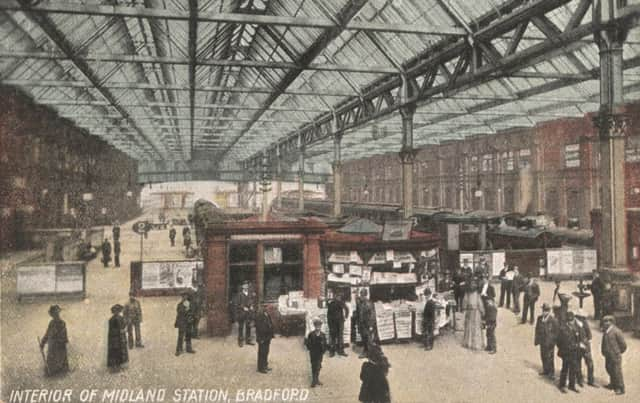

Hide AdThey were by no means the last to flee, and the book is rich in imagery of Bradford’s transport past – the platforms at the old Midland Station looking like those in the final scene of Billy Liar, shot partly in Bradford, in which the angry hero must choose whether to take the train south.

“Billy was typical of many in the North who felt imprisoned by their surroundings and desperate to escape to somewhere they thought would have more opportunities,” says Mr Chrystal.

Yet the city’s well-charted decline over the course of the 20th century is only part of its story. For 50 years, it turned out Jowett cars, a prestigious marque in their day, from a factory in Back Burlington Street. And its famous department store, Busbys, was Yorkshire’s Harvey Nichols.

Its architecture, too, speaks to the great fortunes built in Bradford. The tiled corridor of the Midland Hotel’s restaurant, and the telling hall of the Yorkshire Penny Bank, are monuments to provincial capitalism – as are the slum back-to-backs not far away.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe city’s religious heritage, too, has been preserved in old photographs.

“You can write about beautiful churches until the cows come home, but in a place like Bradford there are also wonderful synagogues and a good few mosques whose architecture is breathtaking,” says Mr Chrystal.

“It’s like going to Morocco or Tunisia – yet it tends to get overlooked by historians.

“But it’s the kind of stuff, quite apart from the textiles, that Bradford really should feel proud of.”

Bradford: Unique Images from the Archives of Historic England, by Paul Chrystal, Amberley Publishing, £14.99.