Annals of secret history

William and Sylvester Petyt did very well for themselves. From obscure beginnings on a Yorkshire farm, they went on to high-profile legal careers, left fortunes in their wills, and bequeathed a fascinating, now almost secret, library to Skipton. Three hundred years on, their great-great-great-great-great-great-great-great grandniece Angela Petyt sums up their achievement. “It was a real rags-to-riches story,” she says.

“I suppose they’re the stars of the family, the ones we’ve always talked about.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe Petyts, sons of a yeoman farmer in the village of Storiths, near Bolton Abbey, moved effortlessly from rural to metropolitan. The elder brother, William, was born in 1635; Sylvester followed three years later. They were educated at Ermysted’s Grammar School in Skipton and studied law in London, rising to the top of their profession.

William, a leading constitutional scholar, died in 1707. Sylvester, who had a profitable money-lending sideline, died in 1719, leaving the 18th century equivalent of almost £3m and the mysterious instruction that he should be buried “ten feet deep between three and four o’clock in the afternoon”.

They had accumulated influence and wealth – and, crucially, books – and more than fulfilled their family motto, a pun on their Petyt/petit surname: “He who is called small shall become great.”

The motto features on the portrait of the bewigged Sylvester gazing sternly down from the wall of the Petyt Library, the brothers’ collection of 5,000 books, pamphlets and letters that has been housed in Skipton’s public library for exactly 100 years this year.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

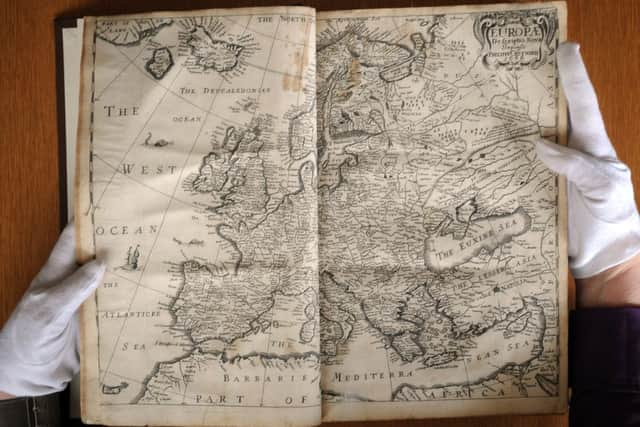

Hide AdThe collection, in Skipton Town Council’s trust, includes 15th century Bibles, 17th century atlases and a vintage copy of the work on which Shakespeare based his history plays.

Daniel Defoe sang the library’s praises after passing through the town on his 1720s tour of Britain, expressing surprise at finding “so handsome a town in so mountainous a country”. So much history under lock and key in busy Skipton, with market traders outside selling extra-large dishcloths, “roast knuckle bone” and Tour de France mugs.

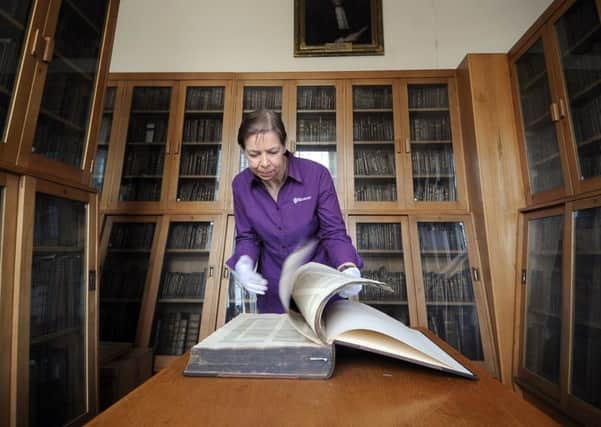

“I’d guess that a very small percentage of people in Skipton know about the Petyt Library,” says Gill Taylor, its custodian. “I suppose it’s out of a lot of people’s area of interest. I’ve had people come in here and say: ‘Oh, it’s just a pile of old books.’”

Some of the titles of those books – brown-bound with gold-lettered spines - certainly discourage casual browsing. True, there are centuries-old editions of works by Homer, Virgil, Chaucer, Milton and Dryden. But Considerations upon the Lives of Alcibiades and Coriolanus, Discourse Concerning Evangelical Love and Sermon on the Baptising of Infants lack some of the attention-grabbing brevity of, say, The Canterbury Tales, Paradise Lost or All for Love.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdYou don’t, however, have to delve far for real treasures. Gill Taylor picks a key from 32 hung on a board and unlocks a glass-fronted cabinet. Inside is a hefty 1580s edition of Holinshed’s Chronicles of England, Scotland and Ireland, one of Shakespeare’s key sources for his history plays – most controversially for Richard III.

The book’s description of Richard sows the seeds of the king’s evil reputation. He was, it says, was “of body greatly deformed, the one shoulder higher than the other”, with a cruel face that hinted of “malice, fraud and deceit”. Fact or propaganda? Whichever, it’s a quiet thrill to read the description in a copy of the Chronicles as old as the one Shakespeare himself would have read.

Another page of the Chronicles lists the Yorkshire “ports and creeks” which “seafaring men do note for their benefit”: Runswike, Robinhoodsbaie, Whitbie, Scarborow, Fileie, Flamborow, Bricklington, Horneseie Becke.” All survive today (in different spellings) except the last – Hornsea Beck, long washed away by the sea on East Yorkshire’s ever-eroding coast.

In a modern world of libraries offering wi-fi, creches and coffee mornings, the Petyt is a collector’s item in itself, particularly for people interested in legal and religious history and the English Civil War. Here, for instance, is a copy of a letter written by Oliver Cromwell about the Siege of Gainsborough in 1643. He reports: “General King slaine, it is supposed... General Cavendish certainly slaine.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe Petyt collection has moved around the town over the three centuries since it was bequeathed, with spells in the grammar school and the parish church, where damp and mice reputedly took their toll.

Probably no-one knows more about the men who bequeathed it than Angela Petyt, born in Wakefield and now living in the Rossendale district near Burnley. An expert in family history, she has researched their lives and careers and remembers copies of their portraits in her family home when she was young.

“I grew up listening to tales about them and as a family we’re obviously very proud of what they did,” she says. “They were so grateful for the opportunities they’d had that they wanted to give something back to their community in Yorkshire.”

Between them, the brothers – neither of whom married – left most of their money to charitable causes. They made bequests to clothe poor children, endow Skipton Girls’ High School and a school near Storiths, and help fund the Cambridge University education of pupils from Ermysted Grammar School (which houses a portrait of William).

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdDuring the 19th century, their trustees also reputedly doled out money to hundreds of people claiming to be poor relations of the brothers. Many of these bequests are recorded on an arch-like “Dole Board” in Skipton Parish Church.

As for the Petyt Library... “Some of the books are very obscure,” admits Angela. “But there will always be someone – students, researchers – who’ll be interested.”

Or more general readers. Back in the library, Gill Taylor reaches down a heavy 1480s Bible and carefully places it on the table. It has exquisitely illuminated pages, with blue, yellow, green and red flowers blooming in a great curly capital E.

A 17th century atlas shows oceans bobbing with galleons and sea monsters; elephants patrol India and rather dainty clumps of trees suggest the jungles of Brazil. There’s a 17th century History of the Whole World which lists the major towns in English counties. Yorkshire’s were reckoned to be York, Hull and Helmsley.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAnd there are books that remind you of past readers. One has a bookmark, probably from the 1930s, advertising “Albert Smith, High Class Boot and Shoe Repairer, Keighley Road, Skipton” and “Dorothy Ward, Handloom Weaving and Handmade Goods”.

All this thanks to two 17th century brothers from a Yorkshire farm. As their great-great-great-great-great-great-great-great grandniece says: “I’m proud to be a Petyt.”

With thanks to North Yorkshire County Council Libraries, which runs Skipton Library. The Petyt Library can be visited by appointment. Ring 0845 034 9538 or email [email protected].