The bitter battle that left country in turmoil

TO some people the name “Cortonwood” means little or nothing, but for many others it is synonymous with one of the most bitter and violent disputes in British industrial history.

The 1984-85 Miners’ Strike was the most divisive confrontation of Margaret Thatcher’s 11 years in power, one that pitched striking miners against the police, family members and communities against each other and changed the industrial landscape forever. And it was at the Cortonwood pit, in the heart of the Yorkshire coalfield, where it all started 30 years ago this week.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdCortonwood stood at the head of the Dearne Valley, where for a century around 30 collieries had employed some 30,000 men. The men who worked there were told they would be re-employed, just down the road at Elsecar, and the implication was that they would still have jobs for life. But the National Union of Mineworkers, led by the charismatic Arthur Scargill, saw the closure as the beginning of the end of Britain’s mining industry.

The NUM President warned that drastic action was needed and his loyal troops in Yorkshire, soon to be branded Arthur’s Army, heeded his call to arms. The coalfield was brought to a halt as pit after pit came out on strike.

Scargill was emboldened by his previous successes - in 1974 the miners had played a large part in bringing down the Heath government after the Conservative Prime Minister had put Britain on a three-day week to try and conserve fuel, and had called an election on the issue of “Who runs the country?”

There was a groundswell of support for the miners, who were seen as men doing a crucial job under difficult conditions, but crucially Scargill had not called a ballot and as the strike rumbled on cracks started to appear in his campaign. Not only that but he was up against a more formidable political opponent than Edward Heath.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdMargaret Thatcher swept to power in 1979 on a tide of anti-union feeling after the “winter of discontent” and vowed that her government wouldn’t be humiliated by Scargill’s miners.

She avoided a miners’ strike in 1981 by backing down because coal stocks were low but believed that a strike was inevitable. She made her plans carefully ensuring that vast stockpiles of coal were built up to enable the country to keep going in the event of any industrial dispute.

She appointed Ian McGregor to run the National Coal Board, a man whose record in the United States had shown he was capable of taking on and defeating the unions. The Tory leader also found powerful allies in the national press, which launched a campaign of vilification against Scargill, and perhaps more surprisingly within the ranks of the NUM.

While the strike spread and remained solid, especially in Yorkshire and South Wales, the men of Nottinghamshire, where conditions were better and wages subsequently higher, demanded a ballot before they would follow the strike call. Scargill’s refusal to hold a ballot also meant he didn’t get political backing from Neil Kinnock and the Labour Party.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAs the strike wore on the role of the miners’ wives became crucial within the mining communities of Yorkshire. Traditionally, the women had run the home and the men had been the breadwinners, but suddenly the women were out of the kitchen and on to the streets, marching alongside their men and raising funds for the strike appeal.

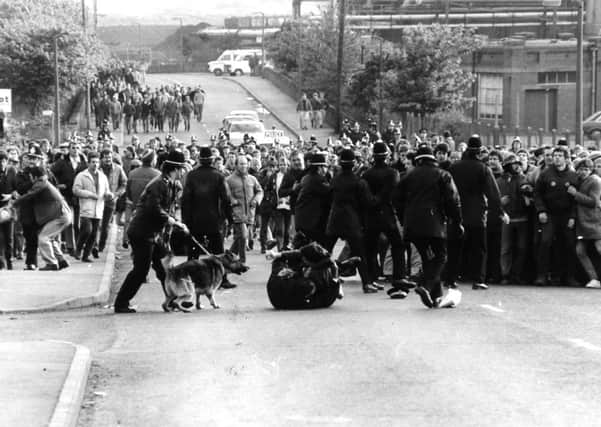

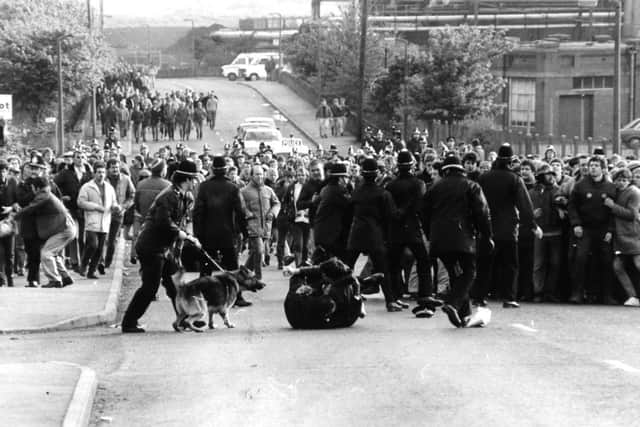

However, as tensions between miners and police increased, a confrontation seemed inevitable. And it duly arrived on June 18, 1984, on a hot summer’s day at Orgreave Coking Plant, near Rotherham, in South Yorkshire.

Previous encounters between Scargill’s flying pickets, sent to “persuade” coal delivery lorries or working miners not to drive through their ranks, and the police, were marked by a degree of respect, at least for each other’s strength.

But Mrs Thatcher had an army of her own to counter Scargill’s “troops”. An unprecedented force of police had been gathered from all over the country, trained to the hilt and armed with truncheons, helmets and riot shields.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdWhile relations between local police and miners had been generally cordial, the arrival of the Metropolitan Police changed all that. Some of them taunted the striking miners, who were having to rely on food from soup kitchens, by waving wads of cash from the coaches transporting them from the scene of conflict; others admitted to getting enough overtime to pay cash for conservatories or new cars.

So when the thousands of miners gathered at Orgreave were confronted with 4,600 police officers, many in riot gear, and 40 mounted officers, tempers boiled over. The mounted police cavalry charge, culminating in miners being beaten with batons, was the climax of shocking scenes of violence.

Orgreave marked a watershed not only in the strike, but also in industrial relations in this country. Mrs Thatcher had further angered the mining communities by describing men previously thought of as the salt of the earth as the “enemy within.” Attitudes hardened on both sides and talks aimed at ending the dispute broke up in July.

As the stalemate continued the NCB encouraged pit managers to call potential strike breakers and when a handful of men defied their local union and went back to work, violence flared again. Hatfield in South Yorkshire was the scene of two days of rioting, which locals described as “Belfast on our doorstep.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdBy the autumn public sympathy was turning in favour of the government. When an IRA bomb exploded at The Grand Hotel in Brighton, where the Cabinet was staying, some picketing miners celebrated, thinking Mrs Thatcher might have died in the blast.

At the end of November there was further loss of support when a taxi driver taking a strike-breaking miner to work was killed by a lump of concrete dropped on to his vehicle by striking miners.

There had been other fatalities in the dispute, as well as serious injuries, but for many moderate miners, under severe financial pressure to return to work, this was the last straw.

By February 1985, around 900 miners had abandoned the strike and at the pit gates, handfuls of pickets made desultory shouts of “scab” as the trickle of working miners became a flood.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe writing was on the wall and Scargill’s delegates’ conference finally recommended an orderly return to work, and on March 5 the men marched back in, with their heads held high and banners waving. As they trooped back to work some still sang “We’ll support you ever more,” but many more remained silent.

In the end the strike was a devastating defeat for the miners and a political triumph for Margaret Thatcher and her government. It was a turning point, too, in industrial relations in Britain.

The strike split the nation and three decades later it still arouses anger and bitterness among those who were there on the front line.

Looking back at anger – lessons from Orgreave flashpoint

Thirty years on, two academics from Sheffield Hallam University talk about their memories of the miners’ strike.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdBACK in the summer of 1984, Dave Waddington was a young ethnographic researcher who spent time on the picket lines and witnessed the clashes between miners and police at Orgreave, in South Yorkshire.

Prof Waddington, now head of Sheffield Hallam University’s Communication and Computing Research Centre (CCRC), remembers the day well. “I was living in Huddersfield and on the day of Orgreave, I drove and parked at the top of Handsworth Hill.

“As per usual there were a couple of police. The surveillance at the time consisted of parked up pairs of policemen taking down your number plates.

“Although it was sweltering, it seemed like just another day but there were lots of miners and even more police officers. Something was definitely afoot – there was a roadblock around Nottinghamshire and Derbyshire so that the miners weren’t allowed to reach their destinations and were pushed back to Orgreave.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“I was determined to get in the thick of it. I remember pushing up against this young police officer and thinking he could be one of my kids, the fear on his face.

“The police or pickets would suddenly yell, ‘man down’, or sometimes more comically, ‘has anyone lost a brown size nine? – it smells a bit’.

“The horses came in quite suddenly and uncompromisingly on that day – it was different than on other days.

“One incident was very pivotal in my view. The miners liked a laugh, and these young guys were rolling a tractor tyre they’d appropriated from a nearby scrap yard down the hill towards the police lines, and they made like they were going to propel it directly into their ranks.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“It spun round like a coin before collapsing, and suddenly I thought it was going to backfire on these lads because a handful of officers angrily broke ranks but immediately thought better of it. But when these guys did it for a second or third time, these police were let off the leash.

“At that point a lot of people started running. I stood for as long as I dared, but then started running across this small bridge, the police thundering up behind us on horseback.

“Self-preservation took root and I remember rushing into the passageway of two houses and cowering with a guy from Derbyshire as the police ran up the hill, it was like something out of a science fiction film.

“What happened at Orgreave consolidated a lot of what I believed, politically and intellectually, at the time.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“Some of the lingering impressions I have of Orgreave still force me to do a double take and ask, ‘Did that really happen?’”

Richard Severns is an associate lecturer in policing and counter terrorism at Sheffield Hallam University, but 30 years ago he was a detective based in North East Derbyshire.

“During the miners’ strike I was transferred into the damage squad – a group of police that was investigating criminal damage as a result of mass picketing. I worked in north Derbyshire – right between Yorkshire and north Nottinghamshire. The area attracted a lot of mass picketing at Shirebrook and Bolsover.

“We used to get a lot of conflict between groups of striking miners and those who were still working – there was a lot of criminal damage and assaults. A lot of the damage was when working miners were bussed in in cages and they used to get ambushed by some – not all of course – but some were hellbent on criminal activity.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“There were differing views between police officers as well. We had a lot of Met bobbies involved who had a totally different view to us. But I’d worked in the industry at a coking plant in Chapeltown so I had worked with a lot of NUM members, in fact I lodged in Shirebrook with a family who were on strike.

“My own opinion is that if Arthur Scargill had had a national ballot he might have won it and had a lot of public sympathy.”

Having done 30 years of policing Mr Severns now gives seminars on policing and the policing of political protest.

“The police learnt a lot from the miners’ strike and it’s moved on. The force talks to people more now.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“The police force used to be very defensive – you’ve got to accept mistakes were made. But now you’ve got to understand where people are coming from and facilitate that protest.

“It’s all right apologising but it’s for something in the past. Sometimes people today try to judge policing that happened in the past by standards today, but you have to understand the miners’ strike in the context of that time.”