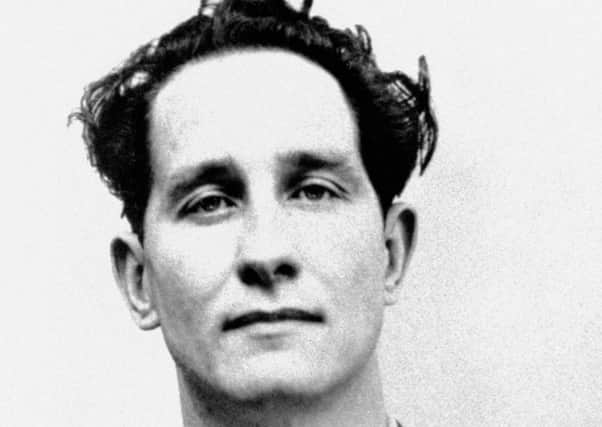

Colourful life of a fugitive who evaded the reach of British justice for 35 years

He might have been involved in the crime of the century, but Great Train Robber Ronnie Biggs’s place in the annals of crime owed more to his status as a notorious fugitive than his prowess as a villain.

His conviction for his part in the most celebrated robbery in the history of British crime and his subsequent escape and high-profile life in Rio de Janeiro brought him the sort of worldwide notoriety in which he seemed to revel and which his early life had seemed unlikely to ever provide.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdRonald Arthur Biggs was born in Lambeth on August 8, 1929, and his first court appearance came as a 15-year-old. His crime? Stealing pencils from Littlewoods. It was the start of a litany of convictions for petty offences, but 13 years later he was given the chance to play a bit part in a robbery on an altogether grander scale. By accepting it, he set himself on the path to a lifetime of infamy which would see him the subject of countless documentaries, films and books.

Joining the gang which was to hold up the Royal Mail night train as it travelled from Glasgow on August 8, 1963, Biggs, who that day would celebrate his 34th birthday, was to find a driver for the train. It was a crucial part of a meticulous plan, but the man he chose struggled with the controls and the train’s legitimate driver, 57-year-old Jack Mills, was coshed with iron bars and forced to move the train. Mills never really recovered from his injuries and died seven years later.

The death of an innocent man was an inconvenient fact many later portrayals of the Great Train Robbers would overlook as they cast the men as daring, lovable rogues.

Certainly, the hold-up, at Sears Crossing in Buckinghamshire, was planned in minute detail and, with the gang seizing around £2.6m it, initially at least, was a spectacular success. However, as they shared out the proceeds at Leatherslade Farm – Biggs taking around £148,000 – the police were hot on their scent and the heist began to unravel.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdQuitting the farm in a hurry, the robbers left behind scores of tell-tale fingerprints, including a large number on the Monopoly board which they had played with real money. It was then but a matter of time before most of the ringleaders were rounded up.

Twelve men were eventually convicted of crimes relating to the robbery, with policing believing four of those involved evaded capture. However, for Biggs it was only the start of his story.

Sentenced to 30 years behind bars on April 15, 1964, he was to serve just 15 months in prison. On July 8, 1965, while other prisoners created a diversion in the exercise yard, Biggs scaled a wall with a rope ladder and dropped onto a furniture van parked alongside. It would be the last Britain would see of him for more than three decades.

After a brief stopover in Paris for £40,000 worth of plastic surgery to change his appearance, he travelled to Australia, entering the country on a false passport and using an assumed name. For several months he ran a boarding house in Adelaide, using the name Terry King, and in June 1966 his wife Charmian and two children joined him, also on false passports.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe family moved first to Perth and then to Melbourne, where Biggs took a job as a foreman carpenter at a local airport in the name of Cooke. In 1968 came a breakthrough for his pursuers. Biggs had formed a business partnership with another fugitive from British justice. His partner was arrested and the trail began to hot up.

However, when a Melbourne newspaper published a story that the manhunt was being renewed, Biggs was tipped off. A day before police swooped on his home, he had packed a suitcase and disappeared – without even taking the family. Rumours abounded as to Biggs’s precise whereabouts. The Australian underworld put it about that he had been killed in a plane crash. The truth was no less fanciful.

Biggs was building a new life for himself in Brazil. In the sunshine city of Rio de Janeiro, the fugitive, now calling himself Michael Haynes, carved out a new career as a jobbing carpenter. However, his peace was finally shattered on February 1, 1974, when he was tracked down in Rio by the Daily Express reporter Colin MacKenzie – and shortly afterwards by Detective Inspector Jack Slipper of Scotland Yard. But yet again, the gods seemed to smile on Biggs.

His Brazilian lover, Raimunda de Castro, was pregnant, and, as the father of a Brazilian child, he won himself immunity from extradition. In May 1978, in an interview for the Sunday Times, Biggs told how he learned of the technicality which was to preserve his freedom.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“I found myself in a cell, feeling very sour, with a couple of Rio taxi drivers who shared the bedclothes with me – they gave me the sports pages to sleep under. There I am, all upset, and one of these blokes says to me, ‘If you could pretend to have got a Brazilian girl pregnant, bribe or beg one, do anything, but get one, then they can’t extradite you. Only deport you.’ I said, ‘Look, fellas, you’re not going to believe this, but...’”

Michael, his son by Raimunda, was later to earn renown in Brazil as a pop star and Biggs also made a record, No One is Innocent, with the punk rock group the Sex Pistols in 1978.

Proceeds from the sales weren’t enough to see him through the lean times and he also raised money by selling T-shirts of himself and posing in pictures with Japanese tourists for £25 a time. In January, 1994, he published his autobiography, Odd Man Out. After reading the book, Jack Slipper wrote: “I don’t know if I’d go so far as to say I liked him after reading the book. But I admit he’s a likeable character – the sort of person whose company I’d enjoy if we met, say, on holiday.”

However, for Biggs, the holiday was almost over. At the age of 71, and in failing health, Biggs announced he was ending his 35-year exile. He was penniless and needed vital medical treatment in Britain.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIgnoring protests from his family, including son Michael, who begged him to reconsider, he sent an email to Scotland Yard informing them that he wanted to give himself up. He struck a deal with The Sun newspaper which flew him back to Britain in May 2001 on an executive jet stocked with curry, Marmite and beer.

Explaining his reasons for turning himself in, Biggs said: “I am a sick man. My last wish is to walk into a Margate pub as an Englishman and buy a pint of bitter. I hope I live long enough to do that.”

The wish was never fulfilled. He was immediately arrested on his arrival in this country and found himself back in a dock later that day, a husk of the cocky Cockney villain he had been last time he faced a judge. Transferred to the high-security Belmarsh Prison, he continued serving the sentence he had put on hold three-and-a-half decades earlier.

Barely a month back in his home country, he suffered a fourth stroke and, after a spell in hospital, Bigg was returned to prison where he was fed through a drip as his health continued to decline. Yet even then he hadn’t lost the art of grabbing headlines. Having divorced from his first wife some years earlier, in 2002 Biggs finally married Michael’s Brazilian mother Raimunda in a Belmarsh jail.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdWhile too ill to say his vows – he held up a card which read “I do” – he did manage to sign his name to seal the marriage to the 55-year-old former samba dancer. Various appeals for his early release were rejected and Justice Secretary Jack Straw refused him parole in 2009 and accused him of being “wholly unrepentant” about his crimes.

In one memorable quote, Biggs had said: “There’s a difference between criminals and crooks. Crooks steal. Criminals blow some guy’s brains out. I’m a crook.”

A chancer was how he saw himself, but even Biggs couldn’t dodge old age.

Severely ill, lying in a bed in Norwich Hospital with pneumonia, fractures of the hip, pelvis and spine, by his late 70s Biggs was unable to eat, speak or walk. He was finally granted compassionate release from his prison sentence on August 6, 2009, just two days before his 80th birthday. By any standards it had been a colourful life, one which came to a close yesterday when he died at the age of 84.

Robber in the public eye

1964: Biggs stands trial and is jailed for 30 years.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad1965: After serving just 15 months he escapes from Wandsworth Prison.

1974: Biggs re-emerges in Brazil where he remains despite several attempts to have him extradited.

1998: Phil Collins stars in Buster, a film about the Great Train Robbery.

1998: Biggs suffers his first stroke.

2001: After suffering two further strokes, he emails Scotland Yard asking to come home.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad2002: The first of many appeals to have his sentence quashed is rejected.

2009: Biggs is refused parole by then Home Secretary Jack Straw who later relents when his condition deteriorates.

2013: Biggs dies at the age of 84.