Discovery of children's bodies reveals an insight into city's grim past

Poverty so severe that some children - ravaged by malnutrition and living in slums, breathing in smog from the mills and factories and scarcely seeing sunlight - were barely expected to live beyond 18 months.

But now, archaeologists and scientists are helping us to uncover a side of Leeds that is very different to the cosmopolitan city we know today - and one that could even help the shape modern medicine.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdExcavations at the site where the £165m Victoria Gate shopping centre is taking shape recovered at least 28 bodies, many of them children, buried in the grounds of what was the Ebenezer Chapel between 1797 and 1848.

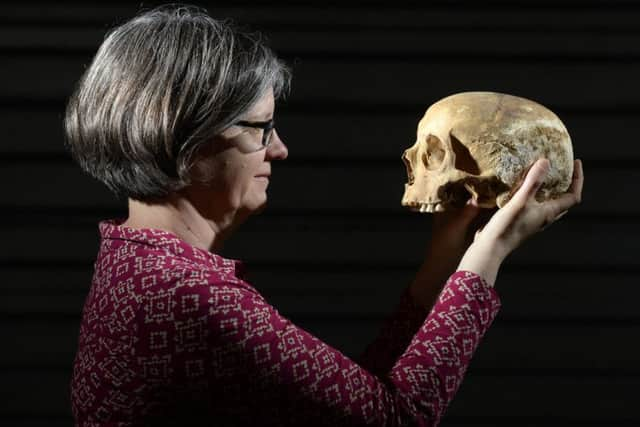

Micro-analysis of bones and teeth have shown that nine of the 12 children had metabolic diseases, including rickets, scurvy and possibly anaemia - and some of those buried could have been taken in a cholera outbreak in the area in 1833, their depleted immune systems unlikely to survive flu, let alone something as serious as cholera.

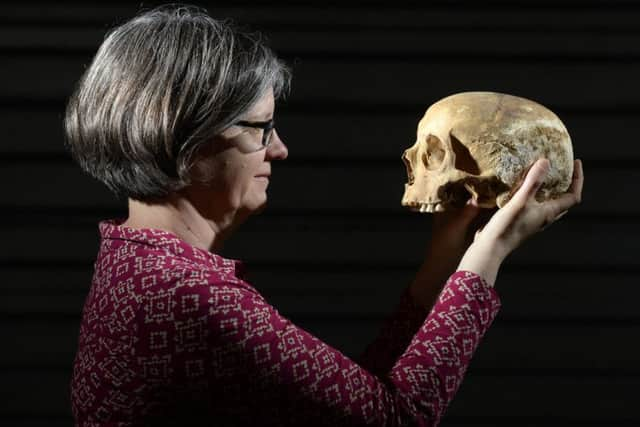

Dr Jane Richardson, manager of Archaeological Services WYAS, which spent over a year on the site, said the finds help them to paint a picture of the individuals living in 19th-century Leeds.

While they also discovered a medieval ditch that pre-dated mapping of the area, and a collection of buttons, glass and pottery, it is the bodies, particularly the children, that are “really fascinating”.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“What makes these stand out is not the fact that remains were found, but the malnutrition they show us,” she said. “It was the most grim part of Leeds at the time, and malnutrition was so prevalent. You can only imagine what these children must have gone through.”

Micro-analysis of the bones has been undertaken by York Osteoarchaeology Ltd.

Director Malin Holst, who previously worked with Archaeological Services WYAS on the analysis of around 60 bodied excavated in Rotherham in 2009, said the severity and extent of the metabolic conditions highlight the effects of overcrowding, lack of sunlight, unsanitary conditions and a diet lacking in essential nutrients.

“We’ve analysed quite a few populations that were very poor, like in Rotherham, but these really stick out,” she said. “The conditions these people had to endure were particularly grim.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“They lived in these hovels in the backyards of back-to-back housing, and you could only get to them through tunnels - which were so small even a coffin could fit through.

“If you can imagine trying to get sewerage or rubbish out, or even just trying to see sunlight - impossible. Children as young as six would’ve been working 12 hours a day in factories, it was just horrible.”

One body, of an eight-to-ten-year-old, had such severely stunted growth it was the same size as a three-to-four-year-old.

Analysis of teeth revealed disrupted growth where they would have suffered periods of no food whatsoever.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdFurther analysis of the teeth is now taking place at Bradford and Durham universities to see what can be learned about weaning and diet in young age, and this research could help with medical advances today.

Miss Holst said: “In this period, when breastfeeding was frowned upon or impossible because mothers were back in the mills, it was common to feed babies and children pap, water mixed with four, and it had no nutritional value at all.

“Analysis like that at Durham and Bradford is an up and coming area, but is already showing results. In Holland, there is a study of hunger in pregnancy in 1944, which has told us that if the hunger was experienced in the first trimester the child stays small for life, but if it is in the second, they are likely to become obese as the body clings to every nutrient.”

Once research is complete, the remains, which were all removed from the site by December, will be re-buried, and all remaining finds will be deposited with Leeds Museum.

‘Filth of all kinds’

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHistorical records from the time include Dr Robert Baker’s 1834 report to Leeds Board of Health, which describes the area and houses around the Ebenezer Chapel.

It said: “I have been in one of these damp cellars, without the slightest drainage, every drop of wet and every morsel of dirt and filth having to be carried up into the street; two corded frames for beds, overlaid with sacks for five persons; scarcely anything in the room else to sit on but a stool, or a few bricks; the floor in many places absolutely wet; a pig in the corner also; and in a street where filth of all kinds had accumulated for years.”

The report was made in the aftermath of the Leeds cholera epidemic in 1832 and pushes for a new drainage system.