Is it time to let wolves back into the British countryside?

“Love them or hate them, sheep have done more damage to the ecology of this country than all the buildings, all the pollution and all the climate change,” says George Monbiot.

“Sheep have completely scoured our uplands, which should be wildlife refuges.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdI catch up with the author and environmentalist just after a storm has engulfed the National Trust over rumoured plans, which it has denied, to ruin the “traditional landscape” of the Lake District by letting trees cover the hillsides and wolves roam where packs of tourists take selfies – a process called rewilding.

According to Monbiot – author of Feral: Searching for Enchantment on the Frontiers of Rewilding – “the Lake District has become a lightning conductor for the much wider debate that needs to happen – and has to happen with Brexit [according to one survey, 58 per cent of farmers voted Leave] – because at the moment the only thing sustaining hill farming in this country is your money and my money.

“It is a massively loss-making activity dependent on £3bn of subsidies. The NHS deficit is also £3bn. It’s not going to be a tough choice for most people what to spend the money on. The Government can no longer hide behind the European Union and say it is out of our hands.”

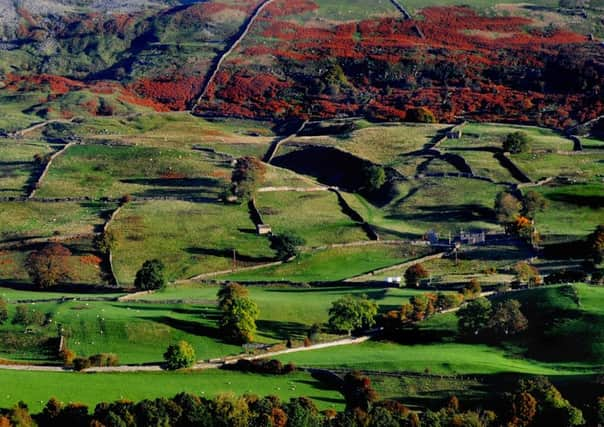

The dry stone walls and barren hillsides that characterise the Pennine landscape and swathes of Yorkshire’s countryside aren’t natural. They are the result of the grazing of thousands of sheep by generations of hill farmers who have scratched a living on the rain-swept hills.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdWhile local farmers want to defend this “traditional landscape”, others, such as Monbiot, want to call time on a landscape that they see as part of an environmental holocaust, the result of a destructive and outdated agricultural system kept alive only by public subsidies.

Left alone, the hillsides would in all likelihood return to natural forest, as they have in other parts of Europe where rewilding has occurred, often due to land abandonment because of rural depopulation.

Rather than managing the countryside like an over-controlling parent, Monbiot argues that humanity needs actually to start letting go and allowing rivers to meander, plants to grow where they want to, and such animals as beavers, lynxes, bears and wolves to eat and be eaten.

While this would give an edge to walking the dog, such “keynote species”, he argues, actually have an impact on the ecosystem far greater than their numbers – and often in surprising ways.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe removal or addition of a predator unleashes effects throughout the food chain called a “trophic cascade”.

For example, the destruction of the shark population off the Atlantic coast of North America led to a collapse of the shellfish industry, as the sharks had kept in check the number of rays, which then preyed on the shellfish.

“I would say to farmers that you can earn £20,000 a year by chasing sheep across the rain-soaked moors, or you can earn more by rewilding because it is very cheap and your income goes up.”

Isn’t he just a metropolitan liberal who wants to destroy the way of life of hill farmers? “No. Quite the opposite. Instead of shutting it down, I think rewilding could be a lifeline for rural communities.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“The only reasonable argument to pay farmers £3bn in subsidies is ecological restoration. Without it, it is hard to see any long-term future to hill farming.”

Rewilding, he says, offers a very different vision of our relationship to the natural world, which has been drilled into us.

“The first animal listed on a clay tablet was a sheep. In the third century BC sheep and shepherds became the repository of innocence and purity, and a refuge from the corruption of city life. Later it was picked up by the Bible, Shakespeare and then Wordsworth among others.”

Terry Smithson, director of operations (North & East) with the Yorkshire Wildlife Trust, says rewilding in principle can have a positive impact. “Some of its principles are what the Wildlife Trust espouse and they are already being applied in places.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHe says there is a growing interest in wilderness experiences in this country. “We’ve been divorced from the natural world but now we’re seeing an upsurge of interest in reconnecting with the wild.”

But this support comes with a caveat. “A full rewilding programme across large chunks of Yorkshire isn’t practical, but the application of its principles would provide significant benefits to society.”

On balance he feels the benefits outweigh the negatives. “We have managed our rural landscape very intensively for a long time and a different form of management based on rewilding principles could address major issues such as climate change and flooding, rather than it just being used to grow food.

“Extensive management of grasslands, hedges and streams can increase the amount of carbon held within soils and hold back water before it causes flooding further downstream. Of course, these areas can still produce food and we can also see wider health, or tourism benefits.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdMonbiot certainly feels the recent pro-rewilding article by the BBC Countryfile presenter Ellie Harrison is a sign that rewilding is beginning to go mainstream.

Yet I wonder whether the Great British Public is ready for the blood and gore of rewilding. We can barely cope with Bake Off moving to Channel 4, let alone Bambi being torn to pieces by wolves.

“Of course nature is harsh, but so are we. The way we treat nature when we are managing it means the mass destruction of wildlife.

“Rewilding is far more uplifting than a managed system where you see only what’s on the noticeboard of a conservation area. It brings back the serendipity – the surprise – into nature.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHe believes it could benefit Yorkshire. “There is a lot of low heather and coarse grass but it could have a much richer landscape. A bleak, blasted and open landscape is far ecologically poorer than landscapes with trees in them.”

Monbiot’s own almost mystical conversion to rewilding occurred when dolphins were jumping round his kayak in Cardigan Bay, and now he is clearly awed by the experience of basking sharks swimming under his kayak in the Western Isles of Scotland this summer.

However, he is at pains to point out that rewilding can only occur with the consent of the rural population – only a fraction of whom are farmers.

Nevertheless he believes we would all reap the benefits.

“Yorkshire has a fantastic outdoors tradition and we should be offering the people of Yorkshire more than just mono cultures.

“ Instead we could see trees growing once again and return to something wonderful.”

A wild idea? Yes, but Monbiot is never one to follow the herd.