Whoops of joy as the regulars return

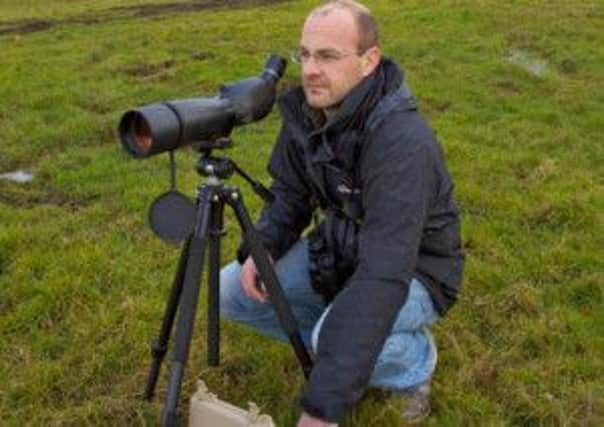

To Craig Ralston, the arrival of magnificent flocks of whooper swans in Yorkshire each winter is like an annual visit from old friends.

As they fly from field to field, feeding across the flat farmland between York and the Humber, he watches through binoculars and telescope for birds which have been making the annual migration from Iceland year after year. He can identify each individual swan by three-letter codes clearly visible on coloured rings fitted to the birds’ legs.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“It’s so exciting to see who has come back to us every autumn,” he says. “A few weeks ago I spotted the bird we know as C9S. He’s been making the thousand-mile journey from Iceland to Yorkshire for each of the past seven years. Another bird, Z5T, was on its own last year – we can always tell which ones are paired – but when he went back to Iceland last spring he clearly found a mate, and now he’s brought her back to us with two cygnets. It makes you wonder how they manage to find the exact same fields.”

Craig is senior manager of Natural England’s Lower Derwent Valley National Nature Reserve, the only regular wintering site for large numbers of whooper swans in the whole of Yorkshire.

Whoopers are around the same size as our familiar resident mute swans, but have a larger wingspan and a black bill with distinctive triangular patch of yellow.

It is estimated that around 500 individual whoopers use the reserve each winter, either staying there after their arrival in November until the journey north in spring, or using it as a feeding and resting place on their migration further south.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThat figure amounts to five per cent of the total population of whoopers visiting the UK for the winter, making the reserve an internationally important site for the species. The attraction is large expanses of floodwater which form each winter on the west side of the River Derwent, and the good supply of food they find in pastures and fields of oilseed rape.

They join large flocks of pink-footed and greylag geese – also from Iceland – and thousands of ducks like wigeon and teal that have migrated from Siberia. In cold spells, like the one in 2009-2010, some flocks of the smaller bewick’s swan also appear. They usually fly from Russia to winter in the Netherlands, but when their feeding and roosting grounds freeze up they move across the North Sea.

While the whoopers from Iceland are in the Lower Derwent Valley, Craig and a team of volunteers catch some of them in order to fit the coloured rings that allow their movements to be tracked. This is vital for ensuring that their regular feeding and resting locations in the UK are known and protected.

To catch the swans a lure of grain, potatoes and carrots is scattered on part of a field they are known to frequent, and when the herd is in place a huge net measuring 30 metres by 15 metres is fired over their heads, giving them no chance of flight.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIn an operation that takes no more than 40 minutes, up to 20 birds are taken from the nets and placed in individual bags until each one is weighed, measured and fitted with the coloured rings bearing three-letter codes. These enable birdwatchers to report their movements when they leave the Lower Derwent.

Says Craig: “We need a large team of people to get the birds out of the nets quickly, so that they are not struggling and injuring themselves. The swans settle down remarkably quickly. I always get nervous when we do it. The first time we fired nets over them I was really worried it might spook them, and the flock might fly off and never come back.

“But my experience with ringing birds is that they are a lot more robust than you would imagine. For the whooper swans, I’d say that being confronted with our nets is probably no more different to a fox coming at them when they’re roosting. At least these birds are lucky enough to get away.”

The work is done in close cooperation with the Wildfowl and Wetlands Trust (WWT), whose reserve at Welney on the Ouse Washes, North Norfolk, is one of the principle strongholds of wintering whooper swans. Many birds use the Lower Derwent as a refuelling stop before flying on there.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdA few years ago the WWT fitted some of the swans with satellite tags to get a more accurate picture of the birds’ migration habits. In late winter they left Welney at 6am in the morning and flew almost 100 miles to the Lower Derwent, where they arrived at about 10.30am. After feeding and sleeping they flew off again at 6pm and by 10.30pm that night they were picked up by satellite flying over Loch Lomond in Scotland. Three hours later they had left the mainland UK behind, and the following afternoon they arrived on their breeding grounds in Iceland.

Satellite tagging is expensive, however, costing in the region of £5000 per bird. The colour rings with their easily legible codes cost about 50p, and are a very cheap way of finding out what happens to the birds, although the system depends on birdwatchers and members of the public reporting their sightings.

Public can play a vital part

Craig says the leg rings have shown that most of the birds they see in the Lower Derwent come back for at least one or two winters, then go elsewhere.

“Members of the public are able to take part in our research on the movements of these beautiful birds, which is what I think National Nature Reserves like the Lower Derwent Valley are all about,” Craig says.

“It is ‘citizen science’ in action.”