Ethical dilemma as scientists reveal genetic codes online

The idea of donating parts or all of your body to science is nothing new. Thankfully thing have come a long way since the days of Burke and Hare who sold the bodies of their murder victims to an Edinburgh anatomist.

That was back in the early 19th century and ever since medicine has relied on public altruism to support ground-breaking research. Each year hundreds of people donate their bodies to medical schools – the one at Leicester has around 1,500 individuals on its books – and thousands more believe in the importance of organ donation.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdSo in many ways the Personal Genome Project is following a rich tradition. There is, however, one crucial difference.

The scientists driving the enterprise are asking for DNA donations from 100,000 living, breathing humans and they’re also refusing to guarantee anonymity. In fact, the crux of the project is to make the genetic information available to as many people as possible.

While not everyone who registers an interest will be accepted, those who do take part also risk uncovering defects linked to serious disease.

So who would be willing to hand over their unique genetic code to the world’s scientists to scrutinise? It turns out there is no shortage of willing guinea pigs. Before the project went live yesterday 450 candidates were on the waiting list. By yesterday lunchtime, while PGP-UK hadn’t quite reached its 100,000 target, the website had been inundated with prospective donors.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

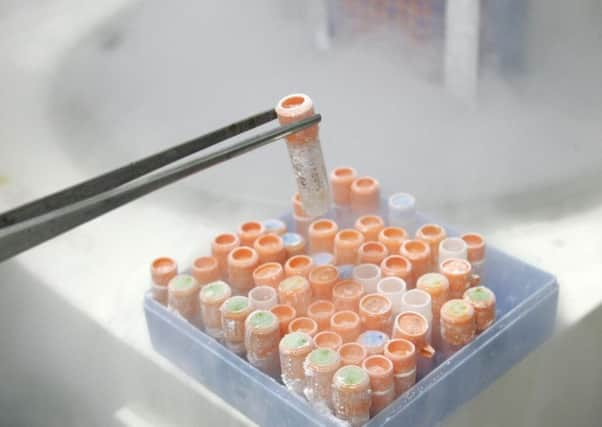

Hide AdVolunteers will be asked to provide samples of blood, saliva or skin cells for analysis. While there is a four-week cooling- off period, once the genomic information has been gathered those who choose to continue will be told of significant findings linked to diseases such as cancer or Alzheimer’s.

Those behind the project obviously believe that honesty is the best policy. They admit that participants could be identified by third parties motivated by interests other than science and clearly state that their may be ethical and legal implications around issues like paternity.

However, there are some who believe that PGP-UK’s upfront stance doesn’t go far enough and that those who do hand over their DNA could end up regretting it.

“We are currently undergoing a technological revolution in genetics,” says Dr David King from the watchdog group Human Genetics Alert. “It is widely expected that these changes will bring major health benefits. However, the human genetics revolution also raises profound social and ethical problems, including a possible resurgence of eugenics. There is a widespread concern that genetics is running far ahead of society’s ability to cope with these issues. We would strongly advise people not to give their genetic information to a project which will share it with the rest of the world.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“Once your data is online, you will never be able to recall it. The project’s informed consent procedures are not valid because they do not tell you about all of the risks.

“Amongst the risks they do not mention is that once you are identified your movements can be tracked by intelligence services, like the NSA, or you may be targeted for unwanted drug marketing by pharmaceutical companies.

“Secondly, your data may be used without your knowledge in projects which you may ethically object to. For example one of the project’s backers, BGI, is using genome sequences to try to identify IQ genes.”

Before qualifying to take part, candidates will have to score 100 per cent in an online test designed to ensure they understand what it means to donate their genome to science. They can also drop out of the project at any time, but there is no way of removing their information online.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“Patients who take the altruistic route to allow their genomic information to be used for research need to feel confident that their data will be treated with care and dignity,” says Sharmila Nebhrajani, chief executive of the Association of Medical Research Charities. “And for most people that will mean with their confidentiality respected.

“Social media does show us that notions of personal privacy are changing, but those who decide to join the project should understand the implications. The data that is revealed is a permanent marker of them as individuals and indeed not only of them, but also of their families.”

• To find out more about the Personal Genome Project UK go to www.personalgenomes.org.uk