EXCLUSIVE: Lily Cole speaks for the first time about her new role at the Brontë Parsonage Museum

When it comes to appointing high- profile names to champion the work it does, the Brontë Parsonage Museum has form. In 2016, The Girl with a Pearl Earring novelist Tracy Chevalier was brought in to support Charlotte’s bicentenary, then last year poet Simon Armitage worked on Branwell’s 200th. The bicentenary commemorations continue this year, with the spotlight falling on Emily, and a few weeks ago the museum announced that Lily Cole would be its creative partner.

It seemed an inspired choice. A model, actor and businesswoman, Cole has become a bit of a role model and, as a fan of the Brontës, and Emily in particular, the museum looked like it had scored a coup.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHowever, not everyone saw it that way and Cole’s tenure got off to a something of a rocky start when critical comments about her appointment made in a blog by a disapproving Brontë Society member went viral.

His gripe was the post should have been given to a writer, the inference being that a public face like Cole was a bit of a publicity stunt. As a number of authors and literary scholars jumped to Cole’s defence, her own dignified, articulate and measured response was published in the Guardian and when we meet in Haworth she hopes the furore is behind her as she looks forward to the next 12 months helping to celebrate Emily’s legacy.

“Wuthering Heights is one of my favourite books; I have read it multiple times over the years,” she says. “And Emily’s relationship to nature and to the landscape has always resonated with me – I am a nature person at heart. In Wuthering Heights she creates a whole world, as all great novels do, that feels completely truthful and authentic – and the characters are so real. I think Heathcliff is one of the most powerful fictional characters in literature.”

Cole has taken Heathcliff as a starting point for a short film that she will be producing which is currently at the writing and development stage. It will explore the connections between the origins of Emily’s famous anti-hero, found by Mr Earnshaw abandoned as a child in Liverpool, and the real foundlings of the 19th century in a new partnership with the Foundling Museum in London, of which Cole has been a fellow since 2016. Established by Thomas Coram in the 18th century, the Foundling Hospital took in children whose parents were unable to care for them.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“I have already done a lot of research at the Foundling Museum,” says Cole. “Women took children there when they couldn’t support them or if the child was illegitimate.

“Originally there was a lottery system for admissions to the hospital whereby a woman had to pull a ball out of a bag and later this was replaced by a petition system.”

This latter system, while relying less on the vagaries of chance, was more judgmental, with the woman being obliged to prove that her baby was illegitimate and that she herself was of a good moral character.

“An ‘enquirer’ would then go and interview people who knew the woman to check up on her story,” says Cole. “We found incredibly rich – and sometimes quite upsetting – documents which show how moralistic that system was, but it also offers a real insight into what England was like, particularly for women, at that time.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“I have been looking through the archives there at years that have resonance – so 1764, which is the year that Heathcliff was born, 1818 when Emily was born, 1848 when she died – and immersing myself in the research to try to understand the society that Emily was living and writing in. And because her father Patrick was a social campaigner I think Emily would have been aware of some of the social issues of the time.”

While she was visiting Haworth, Cole stayed at nearby Ponden Hall, often cited as a possible model for the Wuthering Heights farmhouse, an experience she found inspiring. “It was magical,” she says. “I was so excited to see the window that Emily drew when she was 10 years old, and that had inspired that infamous scene in Wuthering Heights.”

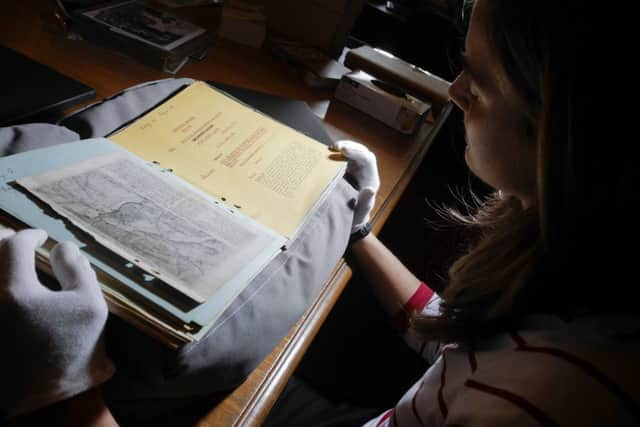

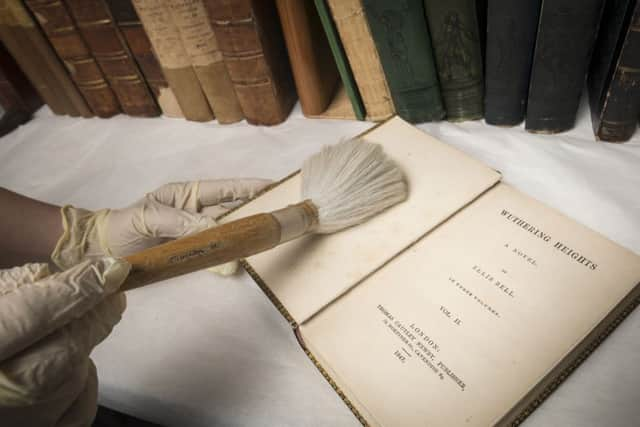

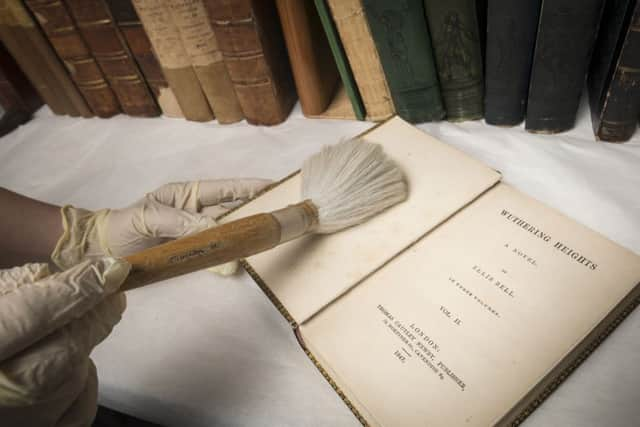

She explored the landscape, walking across the moors to Ponden Kirk – the inspiration for Penistone Crags – before returning to the museum to explore archive material in the collection relating to Emily and her work. “There isn’t a lot, as so much has been destroyed or lost over time, but there are some really special objects,” she says. “I didn’t realise that Emily’s handwriting was so tiny. Her poems exist like secret documents and I was perhaps most surprised by Emily’s drawings, for example a beautiful portrait of a wounded hawk that she had apparently rescued. I hadn’t realised she was a talented visual artist.”

Emily is in many ways the most mysterious Brontë. Other than her work – the bold, brilliant one-off that is Wuthering Heights and her powerful, much-admired poetry – she left little behind in terms of letters, diaries and other documents. Much less is known about her than Charlotte, Anne or even Branwell.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdWhat is known, however, is that not only was she a hugely talented writer, she was also a gifted musician and artist. And the programme of events and creative collaborations organised for her bicentenary year reflect this, with Cole being joined by poet and performer Patience Agbabi as writer in residence, land artist Kate Whiteford, who will be exploring Emily’s connection to the Yorkshire landscape, and award-winning band the Unthanks who will be composing and performing a song cycle based on Emily’s poems.

“We decided that as well as marking Emily’s brilliance as a writer, we wanted to look at her wider artistic talents,” says Jenna Holmes, who leads the contemporary arts programme at the Brontë Parsonage Museum. “She was the most accomplished artist and musician of all the family. We selected projects and partners that would reflect these multi-disciplinary interests, but also touch on the themes that resonate with Emily, such as the landscape.”

There was also the opportunity to use Wuthering Heights as a means to investigate contemporary issues still relevant in society today such as identity, belonging and migration. “Lily is a perfect fit for Emily,” says Holmes. “A writer herself with interests in the environment, literacy and the creative arts as well as a social entrepreneur, there are many parallels with Emily’s work. She is a talented film-maker and we look forward to seeing what she creates.”

Other celebrations include a new exhibition, Making Thunder Roar. The show invites a number of well-known Emily admirers to share their own fascination with her life and work and relate it to a piece from the museum collection. They include screenwriter and director Sally Wainwright who chose cuttings of reviews of Wuthering Heights found in Emily’s writing desk after her death; comedian Josie Long who selected the drawing of a window made by Emily when she was a child; and novelist Benjamin Myers who used Emily’s study of a fir tree as inspiration for a poem.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

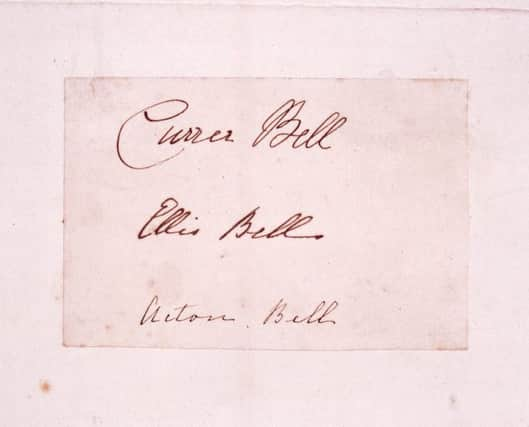

Hide AdCole chose the “Bell” signatures, the androgynous pseudonyms of Currer, Ellis and Acton Bell inscribed on a fragment of paper in the handwriting of Charlotte, Emily and Anne.

Emily’s bicentenary coincides with the 100th anniversary of some women getting the vote and, as a women’s rights campaigner, Cole is mindful of this. “When I started thinking about this last year – the fact that Emily and her sisters had to publish their work under pseudonyms – my initial thought was that this could be a celebration, a positive story about how far we have come as a society in relation to women’s rights,” she says. “But then a lot has happened in the last six months. It does feel like this is an interesting moment and we are pushing that next bit further, but there is no equality yet. We owe it to the women a hundred years ago, some of whom gave their lives, and people like Emily who pushed against the boundaries, to keep fighting for equality.”

Making Thunder Roar: Emily Brontë runs at the Brontë Parsonage Museum in Haworth until January 1, 2019. There is a full programme of events throughout 2018 celebrating Emily’s bicentenary. For details visit bronte.org.uk